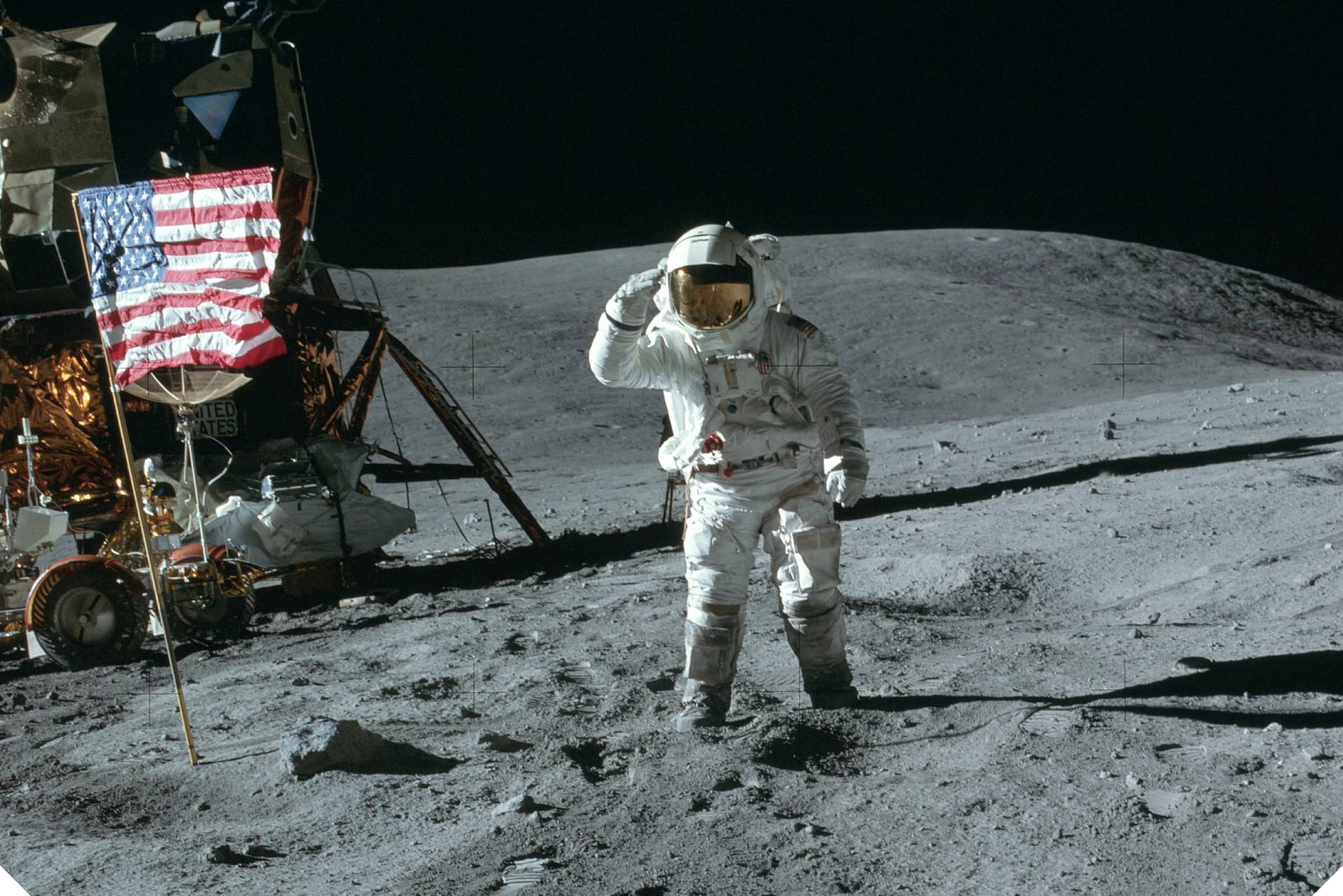

“Charles Duke’s 50-Year Moon Secret Finally Revealed—And It’s Far More Disturbing Than NASA Ever Admitted”

For more than five decades, Charles Moss Duke Jr.—Apollo 16 astronaut, U.S.Air Force Brigadier General, and the tenth human to walk the lunar surface—held tight to a secret he claimed “was never meant to follow him back to Earth.”

Now 89, seated in a quiet conference room in Houston on a cool November morning in 2025, Duke has finally chosen to share what he says he saw in the desolate highlands of the Moon on April 21, 1972.

The revelation arrived during a private recording session arranged by a small group of space-history researchers preparing an oral-archive project.

None of them expected the calm, steady-voiced astronaut to depart from his well-rehearsed mission recollections.

Yet, as a light hum from the old reel recorder filled the room, Duke paused, folded his hands, and spoke words that left the team stunned.

“I’ve carried this long enough,” he said.

“We weren’t alone out there—at least, that’s what it felt like.”

The researchers exchanged quick glances.

The room seemed to shrink around them.

Duke had recounted many untold anecdotes over the years, but nothing as cryptic as this.

The former astronaut leaned back, remembering the dust, the silence, the metallic scent inside his suit.

“It was our second EVA,” he continued, referring to the extravehicular activity he conducted with Commander John Young.

“We were near the rim of Plum Crater.

John was a few meters ahead, taking photographs.

I turned to check on the Rover—and that’s when it happened.

There was a shimmer… almost like heat distortion, but there’s no heat haze on the Moon.

It looked like movement.”One researcher, identified only as Dr.Helen Fletcher, broke the silence.

“Movement? As in something alive?”

Duke breathed out slowly.

“I don’t know.

That’s the truth.

But something shifted, then vanished behind a rise.”

He clarified, quickly and firmly, that he never saw a creature or craft—only “an anomaly,” as he described it.

But in the context of the barren lunar highlands, even the smallest illusion felt profound.

“Your mind plays tricks,” he admitted.

“But that moment… it stuck with me through the years.

And I never told John.

I didn’t want mission control thinking I’d panicked.”

Duke then described the seconds that followed: checking his oxygen lines, glancing at the Rover, scanning the horizon for dust plumes or glints of reflected light—anything to rationalize what he thought he saw.

“But nothing.Just silence.Nothing moves on the Moon unless you move it.”

His team at the time had reported no abnormalities, no reflections from discarded equipment, and no lens flares caught on camera.

And yet the sensation lingered—a fleeting presence at the edge of vision.

Why keep quiet for fifty years?

“I was a military man,” Duke explained.

“You don’t come home from a mission like Apollo and tell people you saw something unexplainable.

Not in 1972.

Not when you’re trying to keep your career intact.

Even the astronauts who reported UFOs back then were cautious with their words.

NASA wasn’t hostile, but they were… practical.

You talk about what you can verify.”

He smiled faintly.

“Besides, it wasn’t fear.

It was curiosity.

The Moon is strange.

Beautiful, but strange.”

Throughout the session, Duke remained composed.

He never claimed extraterrestrial contact.

He never suggested cover-ups.

Instead, he framed the experience as a moment of unexplained visual distortion in an environment where the human brain—isolated, overstimulated, overloaded—can grasp at unfamiliar cues.

Yet the timing of his disclosure has sparked immediate discussion among aerospace historians.

The release of Duke’s statement follows a growing wave of renewed interest in early lunar missions, fueled by recently declassified government research into space-environment perception anomalies and the psychological effects of extreme isolation.

One retired NASA flight surgeon, interviewed hours after Duke’s recording circulated online, offered a cautious interpretation: “Astronauts were operating at the limits of human sensory processing.

The Moon has harsh lighting, extreme contrast, and no atmosphere to soften detail.

A brief misperception doesn’t surprise me.

What’s remarkable is that Duke—one of the most disciplined astronauts of his era—remembers it so vividly.”

Still, speculation erupted almost immediately across social platforms.

Amateur space analysts began dissecting Apollo 16 photographs, highlighting shadows, glints, and blurred shapes near Plum Crater.

Others resurfaced decades-old transcripts, pointing to a brief exchange between Young and Duke shortly after the mentioned EVA:

Young: “You okay back there, Charlie?”

Duke: “Yeah—just checking something.

All good.”

To most historians, the line is unremarkable.

But in the wake of Duke’s confession, it has taken on new intrigue.

When asked whether he regrets staying silent for half a century, Duke chuckled softly.

“No.

I shared what mattered—the mission, the science, the adventure.

This… this was personal.

It didn’t change the mission.

But maybe it changes how people think about the Moon.

It’s not just grey dust and craters.

It’s a place that makes you feel things you can’t explain.”

His voice softened as he described the moment he stepped away from the anomaly and rejoined Young.

“John was focused on the experiments and the rocks.

I didn’t want to distract him.

I just kept going.

But for the rest of the EVA, I had this feeling—like someone was watching us from the ridge.

Not a someone, really… more like the land itself.”

Throughout his career, Duke avoided sensationalism.

His autobiography, Moonwalker, published in 1990, focused on faith, family, and the technical triumphs of Apollo16.

He never hinted at anything resembling this new disclosure.

But age, he admitted, has changed his perspective.

“When you get older,” he said, “you stop worrying about what people think.

You just tell your truth.

And that moment on the Moon—whatever it was—belongs to my truth.”

The recording concluded with a final, striking sentence that has since been replayed thousands of times:

“Before I leave this world, I just want people to know: the Moon still has mysteries, and some of them travel home with the astronauts.”

As the sun set over Houston that evening, Duke’s unexpected confession swept through the global aerospace community, igniting debates that blended science, philosophy, psychology, and the enduring wonder of human exploration.

Whether his experience was a perceptual anomaly, an atmospheric illusion, or something science has yet to define, one thing is certain: Charles Duke’s words have breathed new life into the mysteries of the lunar frontier—and reminded the world that even the most disciplined explorers sometimes return with stories they hesitate to tell.

News

“A Hidden Royal Truth Resurfaces, Forcing William and Harry to Confront a Life-Changing Secret Buried Since Diana’s Final Days…” 👑✨❓

“A Royal Shockwave Erupts as a Confidential DNA Revelation Resurfaces Princess Diana’s Most Guarded Secret—Leaving William and Harry Facing a…

“The Royal Brothers in Shock as Princess Diana’s Secret Mission Is Finally Exposed”

“A Royal Shockwave Erupts as a Confidential DNA Revelation Resurfaces Princess Diana’s Most Guarded Secret—Leaving William and Harry Facing a…

**“Terrifying Underwater Footage Shows the Sunken IJN Akagi Like Never Before 👁️🕳️🕯️”**

“Underwater Drone Reveals Terrifying Secrets of the Sunken IJN Akagi—A WWII Wreck Frozen in Time 👁️🕳️🕯️” Just minutes after the…

New Underwater Drone Footage Reaches the Famed IJN Akagi, Revealing a Chilling Scene That Redefines Everything We Thought We Knew About the Legendary Warship

“Underwater Drone Reveals Terrifying Secrets of the Sunken IJN Akagi—A WWII Wreck Frozen in Time 👁️🕳️🕯️” Just minutes after the…

The Untold Final Chapter of Jay Leno: Hidden Deals, Secret Betrayals, and the Revelation That Shocks Hollywood to Its Core… 🔍✨

Jay Leno Breaks His Silence: The Untold Confession That Rewrites Everything We Thought We Knew About the King of Late…

The Untold Story Behind Jay Leno’s Rise, Reign, and the Private Moment That Changed Everything

Jay Leno Breaks His Silence: The Untold Confession That Rewrites Everything We Thought We Knew About the King of Late…

End of content

No more pages to load