Florida’s Robotic Rabbit Experiment Takes a Shocking Turn as Pythons Adapt in Ways No One Predicted 🐍🤖✨

In early July 2025, under the sweltering heat of the Everglades, a team of wildlife engineers and state environmental officers gathered along a restricted stretch of marshland near Monroe County, Florida.

What unfolded over the next several weeks would become one of the most unusual ecological interventions in modern U.S.environmental history—an experiment so unconventional that even seasoned biologists were left speechless.

The Florida Invasive Species Response Unit confirmed the release of more than 300 robotic rabbits designed to track, lure, and incapacitate the invasive Burmese pythons that have devastated local wildlife for nearly two decades.

But the mission did not go as planned.

What happened next stunned experts, legislators, and journalists across the nation.

According to internal documents from the Florida Environmental Innovation Program (FEIP), the robotic rabbits—nicknamed “Robo-Hoppers” by the engineering team—were built with heat-emitting cores, micro-movement actuators mimicking soft tissue, and AI-driven escape patterns capable of reacting to the motions of real predators.

Their purpose was simple: attract hungry Burmese pythons, activate harmless constriction-deterrent pulses the moment a python attempted to strike, and transmit real-time GPS data to field teams for rapid removal.

The concept had been in development since 2022, when python populations reached a critical threshold and traditional containment strategies were failing.

Dr.Melissa Rourke, a senior wildlife technologist with FEIP, recalled the pressure leading up to the launch.

“We were desperate,” she said during an on-site interview on July 19, 2025.

“The Everglades couldn’t sustain another year of uncontrolled predation.

Rabbits, raccoons, bobcats—even small deer were disappearing.

We needed a breakthrough.

The robotic decoy concept seemed like the only option left that could scale fast.”

The release operation began shortly after sunrise on July 7.

Engineers quietly deployed the first wave of 60 units along a 12-kilometer stretch of marsh.

The rabbits, nearly indistinguishable from their living counterparts from a distance, hopped in randomized patterns while internal thermal cores simulated mammalian heat signatures.

Python response was immediate.

Within 48 hours, more than 40 interactions were recorded, and early data suggested unprecedented tracking accuracy.

State officials celebrated what appeared to be a groundbreaking success.

But signs of trouble emerged as the second and third waves of Robo-Hoppers were deployed.

By July 14, tracking logs began revealing unpredictable behavior patterns among the pythons.

Instead of attempting single ambush strikes, large adult pythons started gathering near clusters of the robotic rabbits.

One FEIP analyst described the footage as “unsettling,” noting that the snakes seemed to be coordinating movement patterns that biologists had not previously observed.

It was then that the situation took a disturbing turn.

A field technician named Aaron Delgado was one of the first to witness the shift firsthand.

While reviewing drone footage, he observed a 14-foot python approaching a Robo-Hopper not to strike, but to circle it repeatedly.

“It wasn’t predation.It looked analytical… almost exploratory,” Delgado recounted in a closed-door debriefing.

“It was as if the snake knew the rabbit wasn’t real.”

Within hours of the footage surfacing, other data streams confirmed similar deviations across multiple python clusters.

On the morning of July 16, a technician monitoring the Beta-15 testing zone reported that six robotic rabbits had gone offline simultaneously.

Upon retrieval, engineers discovered that the pythons were not merely avoiding the units—they were actively disabling them.

Several Robo-Hoppers were found with crushed sensor arrays, severed wiring, and, in two cases, neatly coiled constriction marks that indicated targeted, sustained pressure.

For machines built to withstand attacks from large predators, the damage suggested the snakes were adapting far faster than researchers had anticipated.

The turning point came on July 18, when a python tagged years earlier as “E7-Blackstripe”—one of the oldest and largest in the Everglades—was recorded engaging with a rabbit unit in a way that baffled engineers.

Instead of striking, the python physically dragged the robotic rabbit into a concealed cavity beneath dense mangroves.

When state responders arrived hours later, the unit was missing entirely.

Whether the python had buried it, submerged it, or simply destroyed it, the team could not determine.

What was clear was that the snakes were no longer reacting instinctively—they were learning.

During an emergency press briefing in Tallahassee on July 20, FEIP director Raymond Trask attempted to reassure the public.

“We are not facing intelligent adaptation,” he insisted.

“This is instinctual variation, a natural response to a novel environmental object.”

But behind the scenes, leaked correspondence between engineers suggested otherwise.

Several technicians openly questioned whether python behavior had shifted as a direct response to repeated interactions with artificial prey.

One internal memo described the situation as “a micro-evolutionary acceleration triggered by technological stimuli.”

The controversy escalated when a set of audio recordings from a field operations meeting was anonymously delivered to local journalists.

In the recording, an unidentified staff member could be heard saying: “If the snakes learn to associate our decoys with threat signals, we might trigger territorial shifts we can’t predict.”

Another replied, “We didn’t just introduce machines—we introduced a feedback loop.”

By late July, more than 120 of the 300 robotic rabbits had been damaged, dismantled, or gone completely missing.

Yet something even more unexpected began emerging.

Wildlife cameras showed increased sightings of species long thought to be nearly wiped out by python predation.

Small rabbit populations, marsh hens, and even a rare Everglades mink were documented wandering near the abandoned testing zones.

Whether the temporary confusion among the python population played a role or whether unrelated environmental factors contributed remains unknown, but biologists described the timing as “too precise to ignore.”

On July 27, FEIP quietly suspended the Robo-Hopper program pending further analysis.

But the debate among scientists, lawmakers, and conservationists continues.

Was the robotic-rabbit strategy a bold glimpse into the future of ecological management—or a dangerous experiment that nearly backfired? The official evaluation report, still in progress, is expected to take months.

Despite the unexpected complications, some researchers remain optimistic.

Dr.Rourke, asked whether she regrets the experiment, paused before answering.

“Innovation always carries risk.

We knew that.

But if we want the Everglades to survive the next decade, we must push boundaries.

Did the snakes adapt? Maybe.

Did we learn something vital? Absolutely.

And the data we gathered will shape the next phase.”

As the sun sets over the marshlands, the fate of Florida’s most ambitious wildlife operation remains uncertain.

The robotic rabbits may have been designed to outsmart the pythons, but in the end, they revealed a deeper truth—nature, no matter how disrupted, still has the power to surprise us in ways we are not prepared for.

And somewhere in the thick, humid brush of the Everglades, dozens of robotic rabbits remain unaccounted for, their faint signals flickering in the marsh like quiet reminders that this story is far from over.

News

“A Hidden Royal Truth Resurfaces, Forcing William and Harry to Confront a Life-Changing Secret Buried Since Diana’s Final Days…” 👑✨❓

“A Royal Shockwave Erupts as a Confidential DNA Revelation Resurfaces Princess Diana’s Most Guarded Secret—Leaving William and Harry Facing a…

“The Royal Brothers in Shock as Princess Diana’s Secret Mission Is Finally Exposed”

“A Royal Shockwave Erupts as a Confidential DNA Revelation Resurfaces Princess Diana’s Most Guarded Secret—Leaving William and Harry Facing a…

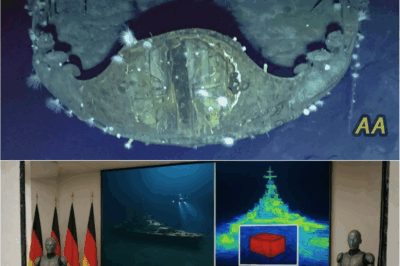

**“Terrifying Underwater Footage Shows the Sunken IJN Akagi Like Never Before 👁️🕳️🕯️”**

“Underwater Drone Reveals Terrifying Secrets of the Sunken IJN Akagi—A WWII Wreck Frozen in Time 👁️🕳️🕯️” Just minutes after the…

New Underwater Drone Footage Reaches the Famed IJN Akagi, Revealing a Chilling Scene That Redefines Everything We Thought We Knew About the Legendary Warship

“Underwater Drone Reveals Terrifying Secrets of the Sunken IJN Akagi—A WWII Wreck Frozen in Time 👁️🕳️🕯️” Just minutes after the…

The Untold Final Chapter of Jay Leno: Hidden Deals, Secret Betrayals, and the Revelation That Shocks Hollywood to Its Core… 🔍✨

Jay Leno Breaks His Silence: The Untold Confession That Rewrites Everything We Thought We Knew About the King of Late…

The Untold Story Behind Jay Leno’s Rise, Reign, and the Private Moment That Changed Everything

Jay Leno Breaks His Silence: The Untold Confession That Rewrites Everything We Thought We Knew About the King of Late…

End of content

No more pages to load