“Titanic’s Tragic Secret: The Heartbreaking Fate of Victims’ Bodies After the Ship Sank—Worse Than You Ever Imagined”

It was the frigid night of April 14, 1912, when the RMS Titanic struck an iceberg approximately 375 miles south of Newfoundland at around 11:40 p. m..

Within hours, the “unsinkable” ship would vanish beneath the icy waters of the North Atlantic, leaving 1,517 passengers and crew dead in one of history’s most infamous maritime disasters.

While the world has long focused on the ship itself, the tragic aftermath for the victims’ bodies has often remained obscured—until recently, when historians and oceanographers pieced together accounts from the disaster and subsequent recovery missions.

In the immediate aftermath, survivors described a horrifying scene.

Margaret Brown, famously known as “The Unsinkable Molly Brown,” recalled the chaos in her lifeboat as passengers clung to the sides, some desperately attempting to reach safety in the freezing sea.

“Bodies floated everywhere,” she wrote in her diary days later.

“Some were clothed, some were not, and many were so cold they drifted like statues in the dark.”

The temperature that night hovered around 28°F (-2°C), a lethal environment that left little hope for those not on lifeboats.

Oceanographers explain that in such frigid waters, hypothermia sets in within 15 minutes, making survival nearly impossible without immediate rescue.

For many victims, this meant that even before decomposition could begin, their bodies were already lost to the icy currents.

The White Star Line, responsible for Titanic’s voyages, immediately organized recovery missions in the days following the disaster.

Between April 15 and May 1912, ships including the CS Mackay-Bennett, SS Minia, and SS Montmagny scoured the debris field, retrieving a total of 333 bodies.

Crew members aboard these vessels recounted the grim work with haunting precision.

One officer described spotting bodies “entangled in wreckage, arms extended as if still reaching for loved ones, faces frozen in eternal expressions of fear and shock.”

Recovery teams faced difficult decisions.

Identification of victims was complicated by the fact that many had no personal belongings, while clothing was often ripped or missing.

To manage limited space aboard recovery ships, bodies in advanced stages of decomposition or beyond recognition were buried at sea, wrapped in canvas or weighted to prevent surfacing.

This practice, while necessary at the time, contributed to the many victims who were never accounted for.

For those bodies recovered, identification was a painstaking process.

Tattooed markings, jewelry, and personal effects were cataloged alongside physical characteristics.

Captain Frederick Fleet, who had witnessed the iceberg strike, assisted in sorting bodies, noting that class distinctions persisted even in death: first-class passengers often had personal effects intact, while third-class victims frequently had none.

Historians later examined accounts from Father Thomas Byles, a priest who died on board, and discovered that many passengers had died clutching letters or prayer books, frozen in a final moment of faith.

Dr.Robert Ballard, the oceanographer who located the wreck in 1985, confirmed that the Titanic’s remains are largely intact, but the surrounding debris field contains human artifacts intertwined with ship fragments.

This gives a haunting insight into the fates of those who were never recovered, preserved only in the depths of the North Atlantic.

Modern studies have used forensic reconstructions to hypothesize the likely decomposition processes.

In the cold, dark waters below 12,000 feet, microbial activity is slow, delaying decay.

This means that victims’ bodies that sank with the ship may remain relatively preserved for decades, slowly dispersing nutrients into the surrounding ecosystem.

Scavenging fish and deep-sea crustaceans played a role in the natural decomposition, consuming tissues over time, leaving skeletal remains mingled with wreckage.

Family members of the deceased faced a grim reality.

Letters from survivors describe how relatives were informed: some were given the unfortunate news of death without ever seeing a body, while others received bodies recovered at sea, sometimes partially decomposed or unrecognizable.

Survivors themselves were haunted by guilt, describing nightmares of people they could not save.

Perhaps the most chilling accounts come from those who witnessed the initial hours after the sinking.

Lifeboats bobbed in the icy waves, carrying both survivors and witnesses to tragedy.

One survivor, Harold Bride, the ship’s junior wireless operator, wrote that “the cries in the water were constant, a sound that chills the soul, many of them swallowed by darkness before we could reach them.

” The frigid sea effectively claimed countless lives before any human intervention could occur.

Scientific expeditions in recent decades, particularly those led by Dr. Ballard and other deep-sea researchers, have documented the wreck’s debris field, observing the remains of the ship’s grand staircase, dining halls, and cabins.

Items once held by passengers—china, clothing, and letters—have been preserved in the sediment.

These remnants offer somber testimony to the lives that were lost and the final moments of those who perished.

In total, it is estimated that of the 1,517 lives lost, fewer than a quarter were recovered.

The remainder likely sank with the ship or were carried away by the currents, their fates unknown.

Ocean currents, water temperature, and scavenger activity all contributed to the dispersal, leaving a silent graveyard across the North Atlantic.

Forensic experts and maritime historians emphasize that the human cost of the Titanic disaster extends far beyond the number of bodies recovered.

The psychological impact on survivors, families, and rescuers underscores the tragedy’s enduring legacy.

Annual commemorations, museum exhibits, and ongoing research ensure that the victims are remembered, while also highlighting the stark realities of life and death in extreme maritime disasters.

Even today, deep-sea expeditions to Titanic reveal occasional human artifacts, reminding the world that thousands of lives were claimed in the cold, dark waters.

Each fragment tells a story of loss, courage, and the limits of human endurance.

Modern technology allows us to revisit the site with remotely operated vehicles, offering unprecedented views of the wreck and, indirectly, the fates of those who perished.

In the end, the tragedy of the Titanic extends beyond the sinking itself.

While the ship rests silently on the ocean floor, the bodies of the victims—whether buried at sea, recovered, or lost to the abyss—serve as a haunting testament to human vulnerability, the unforgiving nature of the sea, and the enduring need to remember those who were lost on that fateful April night.

The story of what happened to the Titanic victims’ bodies is more harrowing than popular imagination allows.

It is a tale of survival, loss, and the deep silence of the North Atlantic, reminding us that while history remembers the ship, the lives and deaths of those aboard continue to resonate more than a century later.

News

“A Hidden Royal Truth Resurfaces, Forcing William and Harry to Confront a Life-Changing Secret Buried Since Diana’s Final Days…” 👑✨❓

“A Royal Shockwave Erupts as a Confidential DNA Revelation Resurfaces Princess Diana’s Most Guarded Secret—Leaving William and Harry Facing a…

“The Royal Brothers in Shock as Princess Diana’s Secret Mission Is Finally Exposed”

“A Royal Shockwave Erupts as a Confidential DNA Revelation Resurfaces Princess Diana’s Most Guarded Secret—Leaving William and Harry Facing a…

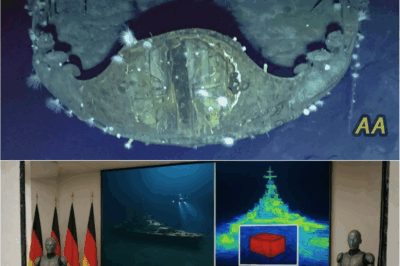

**“Terrifying Underwater Footage Shows the Sunken IJN Akagi Like Never Before 👁️🕳️🕯️”**

“Underwater Drone Reveals Terrifying Secrets of the Sunken IJN Akagi—A WWII Wreck Frozen in Time 👁️🕳️🕯️” Just minutes after the…

New Underwater Drone Footage Reaches the Famed IJN Akagi, Revealing a Chilling Scene That Redefines Everything We Thought We Knew About the Legendary Warship

“Underwater Drone Reveals Terrifying Secrets of the Sunken IJN Akagi—A WWII Wreck Frozen in Time 👁️🕳️🕯️” Just minutes after the…

The Untold Final Chapter of Jay Leno: Hidden Deals, Secret Betrayals, and the Revelation That Shocks Hollywood to Its Core… 🔍✨

Jay Leno Breaks His Silence: The Untold Confession That Rewrites Everything We Thought We Knew About the King of Late…

The Untold Story Behind Jay Leno’s Rise, Reign, and the Private Moment That Changed Everything

Jay Leno Breaks His Silence: The Untold Confession That Rewrites Everything We Thought We Knew About the King of Late…

End of content

No more pages to load