For decades, the Dead Sea Scrolls were treated as a window into the beliefs of an ancient Jewish community, nothing more than fragments of scripture, prophecy, and ritual law. But as scholars revisited the scrolls with modern technology, a different pattern began to emerge—not of Anunnaki or extraterrestrial gods, but of ancient beings whose descriptions echo stories from Mesopotamia, the Hebrew Bible, and myths whispered in every corner of the ancient world. The question resurfaced with new intensity: do the scrolls contain references to Nephilim-like figures, or beings similar to the Watchers and sky-descending entities depicted in Sumerian lore? The answer, as always, is more complicated than a single yes or no. And the deeper one dives, the more the lines between myth, memory, and belief begin to blur.

The Dead Sea Scrolls do not contain the word “Anunnaki.” There is no explicit mention of sky-gods descending in fiery craft or extraterrestrial architects engineering early humanity. But they contain something else—something older, more symbolic, and in some ways more haunting. Hidden in the caves of Qumran were full copies of the Book of Enoch, fragments of the Book of Giants, and other writings long removed from the biblical canon. These texts describe beings called the Watchers, heavenly entities who “descended” to Earth in the days before the Flood. They took human women as partners. They fathered children—giants of enormous strength and knowledge, called the Nephilim. They taught forbidden arts: metallurgy, cosmetics, enchantments, astronomy. And they sparked a crisis so catastrophic that, according to the texts, the earth herself cried out beneath the violence of their offspring.

The Book of Giants, found in multiple fragments among the Dead Sea Scrolls, tells stories that read like a mythic echo of forgotten ages. Giants named Ohyah and Mahway speak in dreams of collapsing heavens and burning landscapes. One giant ascends—or imagines ascending—to meet Enoch, a prophet caught between worlds, to seek answers about their looming doom. These passages feel far removed from standard religious narrative. They contain hints of astronomical symbolism, cosmic rebellion, and a kind of hybrid lineage unlike anything found in mainstream biblical texts. Whoever wrote them believed that the ancient world had been shaped not only by humans and their God, but by powerful beings who crossed boundaries they were never meant to cross.

Some researchers draw parallels between these Watchers and the Anunnaki of Sumerian myth. Both are described as powerful heavenly beings. Both interact with early humans. Both appear in flood narratives. Both are connected to knowledge “from above.” And both vanish into myth, leaving behind stories of tragedy, judgment, and civilizations reset by divine decree. But the scrolls never use the Mesopotamian names. They never frame these beings as extraterrestrials or star-gods. The Watchers are described as angels, disobedient but created beings, not visitors from the Pleiades or Orion. Their story takes place in a theological world, not a cosmic one. Yet the recurring themes—descent, hybrid offspring, lost knowledge—are the same motifs that modern theorists stitch together when they draw comparisons to other ancient cultures.

The scrolls also reveal something remarkable. They expand the Nephilim story far beyond the brief verses in Genesis. Instead of a passing reference to “heroes of old,” they portray a world in which giant hybrid beings roam the land. They speak. They dream. They fear judgment. Their downfall is tied to a cosmic crisis, and their existence is presented not as metaphor, but as a narrative memory of a world before humanity’s reset. The fragments describe violence so extreme that the earth “accused them.” They describe a celestial trial, where the Watchers are imprisoned in darkness, awaiting a final judgment. These details fueled centuries of speculation long before anyone ever used the word “Anunnaki.” And in the 20th century, when the scrolls finally emerged from the caves, they reignited questions that scholars had tried to bury.

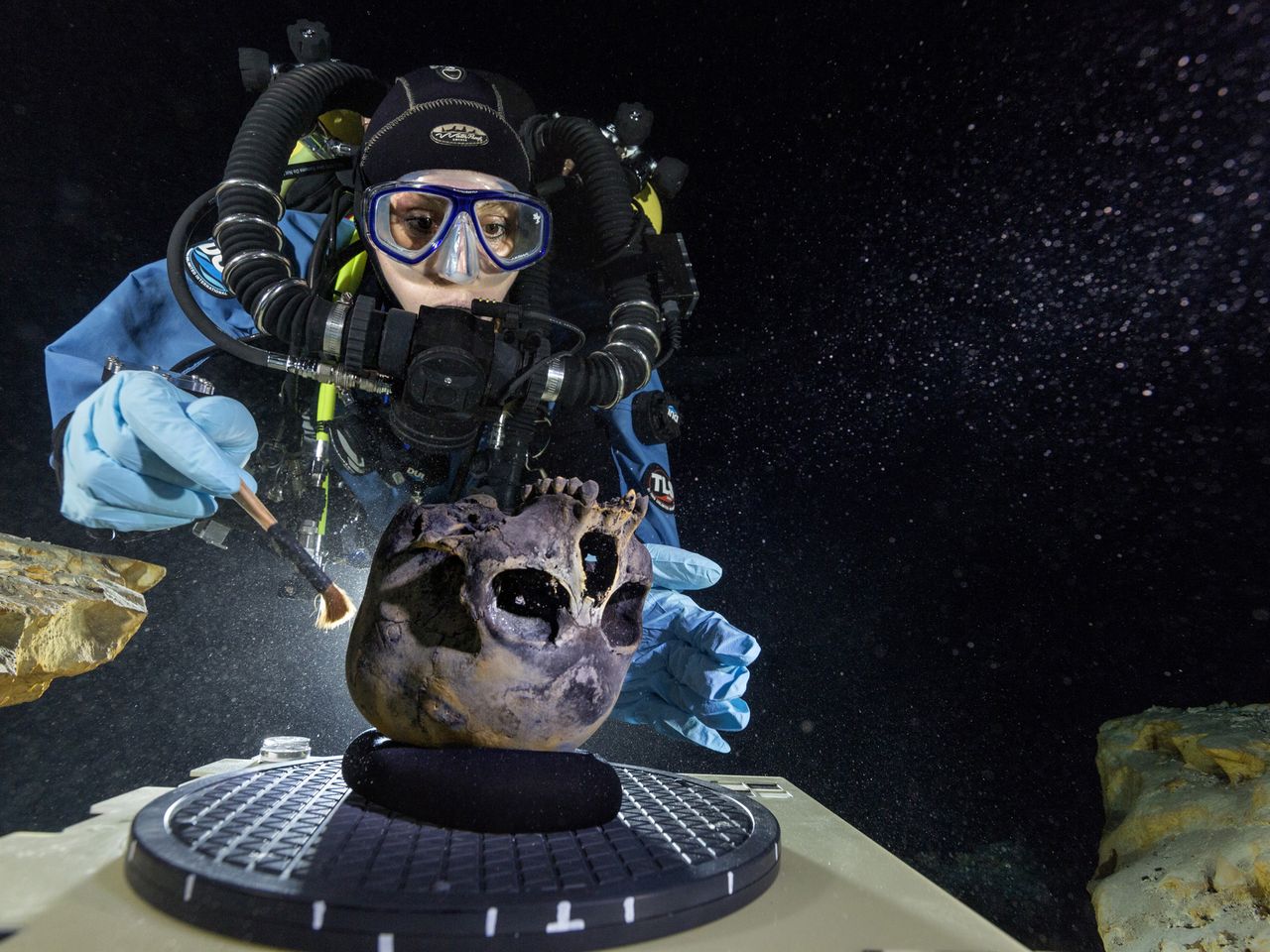

There is, however, a modern layer to the myth. In the age of genetic testing, elongated skulls, and global explorations, some have wondered whether the ancient stories could reflect reality, distorted over millennia. Experimental archaeology has uncovered unusual skeletons—elongated, sometimes massive, sometimes anatomically strange—though none have been definitively linked to non-human origins. DNA sequencing on controversial specimens often produces partial reads, degraded fragments, or sequences that don’t match known databases. Scientists caution that “unknown” does not mean “alien”—it usually means incomplete, damaged, or contaminated. But the mystery persists because the patterns found in the myths persist. Across Sumer, Canaan, Egypt, Persia, and the Levant, stories of heavenly visitors, giant offspring, and catastrophic floods appear again and again. Were these shared memories? Parallel myth-making? Or something older, buried so deeply in humanity’s beginnings that the stories fractured into a dozen different names?

The Dead Sea Scrolls offer no extraterrestrial explanations. They do not rewrite human evolution or prove star-born bloodlines. What they offer is a shockingly detailed account of a forgotten cosmology, one in which divine beings and mortals intersected in ways the later biblical tradition tried to silence. These banned texts present the Watchers not as metaphors, but as real presences in the ancient imagination—so real that the Qumran community preserved their stories even when mainstream Judaism abandoned them. The scrolls act like a missing chapter of ancient belief, not confirming alien theories, but providing the foundation upon which those theories were later built.

What makes these writings compelling is the consistency. The descriptions of hybrid giants. The warnings of forbidden knowledge. The divine punishment that echoes through flood myths in multiple cultures. The sudden disappearance of these beings after a world-resetting catastrophe. These patterns are not random. They reflect a worldview shared by multiple civilizations separated by geography and language. Whether the origin of those stories was supernatural, cultural, or historical is a question scholars still debate. But the myths themselves formed the backbone of Near Eastern thought long before the Bible took shape.

The scrolls, in essence, preserve the raw, unfiltered version of those myths. They offer a picture of the ancient world that is more dramatic, more violent, and more cosmically interconnected than any modern translation of Genesis suggests. They show us a humanity that saw itself caught between heaven and earth, shaped by beings of enormous power and punished for their excesses. They remind us that the earliest storytellers were not interested in making history logical. They were trying to explain a world full of unexplained marvels, tragedies, and structures of origin.

No, the Dead Sea Scrolls do not mention the Anunnaki. But they speak of beings who served the same narrative role—cosmic intermediaries, bringers of knowledge, breakers of boundaries, fathers of giants. Whether symbolic or literal, they haunted the ancient imagination. And through the scrolls, they haunt ours too. Because the closer we look at these texts, the more they remind us of something older than religion, older than civilization, older than history itself: humanity’s instinct to look up at the night sky and ask who came before us—and who might have come from beyond.

News

Princess Leonor and Lamine Yamal Caught Dining Together in Madrid—Is There a Secret Relationship?

LAMINE YAMAL SURPRISED HAVING DINNER WITH PRINCESS LEONOR! Incredible! Princess Leonor and footballer Lamine Yamal have been spotted dining together…

🚨🔥 “Hey, 18-Year-Old, Shut Your Mouth!” Arda Güler’s Fierce Comeback Sparks Global Frenzy After Yamal’s Insults!

In a dramatic turn of events that has sent shockwaves through the football world, Real Madrid’s young prodigy Arda Güler…

“Inside Lamine Yamal’s Secret World: The Untold Story No One Dared to Reveal!”

Everyone knows how talented Lamine Yamal is on the pitch. The young FC Barcelona prodigy is already making history with…

“Messi’s Shocking Prison Visit to Robinho—What Happened Behind Bars Left Everyone Stunned!”

Just days after lifting another trophy with Inter Miami and being honored as a global ambassador of football, Lionel Messi…

“Isak’s Injury Sparks Unimaginable Chaos: The Unseen Consequences for Liverpool!”

The Impact of Isak’s Injury on Liverpool’s Hopes for the Season Liverpool’s recent setback with Isak’s injury has left fans…

“LeBron James Sends Heartfelt Message to Lionel Messi Ahead of Inter Miami & MLS Debut – The Gesture That Captivated Fans! 💬💖

LeBron James Shows Unwavering Support to Lionel Messi Ahead of His Inter Miami MLS Debut As the countdown to Lionel…

End of content

No more pages to load