Archaeologists investigating the ancient ruins of Baalbek in Lebanon continue to confront one of the most enduring engineering mysteries of the ancient world.

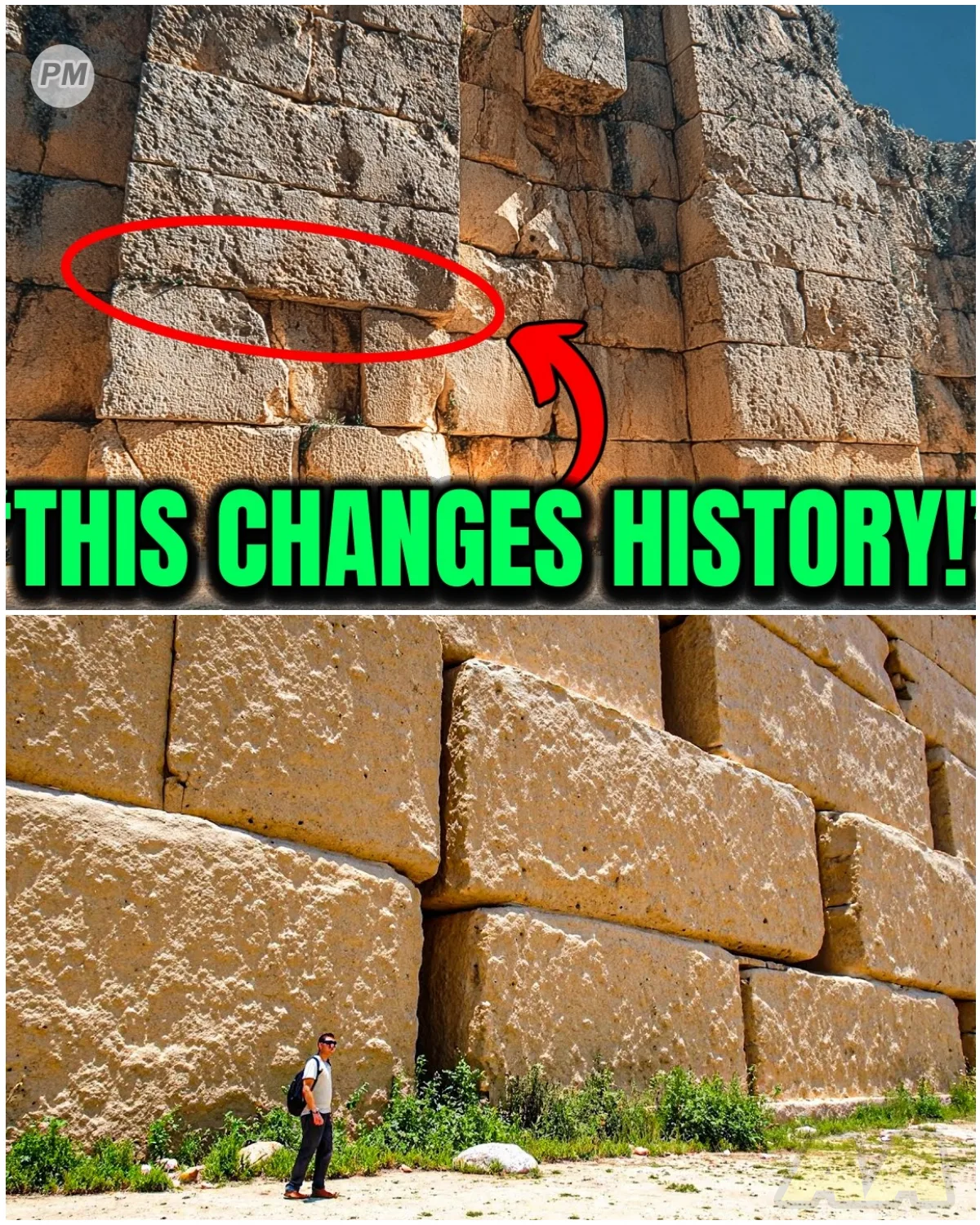

At the center of the debate are several megalithic blocks so large and so precisely placed that no modern crane in operation today can lift or position them.

Their presence raises questions not only about the origins of the site, but also about ancient capabilities that appear to exceed the known technology of any recorded civilization.

The core of the mystery lies in a set of three limestone blocks known as the Trilithon.

Each stone measures roughly 62 feet long, 14 feet tall, and 12 feet thick.

Each weighs an estimated 800 tons—more than double the weight of the heaviest stones known to be transported in modern construction.

What makes the phenomenon more striking is that these stones are elevated more than 20 feet above ground level and fitted so tightly that a sheet of paper cannot be inserted between them.

There is no written record from Rome, the empire credited with constructing the temple complex above the foundation, explaining how these blocks arrived or how they were raised into position.

The Romans recorded virtually every major architectural accomplishment across their empire, from bridges to aqueducts to amphitheaters.

Yet Baalbek, which they renamed Heliopolis, is missing from these engineering reports.

No Roman text references the transportation, cutting, or lifting of the Trilithon stones.

This silence has become one of the most significant anomalies in ancient architectural scholarship.

The enigma deepens with the discovery of even larger unfinished stones still lying in the nearby quarry.

The “Stone of the Pregnant Woman” weighs approximately 1,000 tons.

The “Stone of the South,” identified in the 1990s, weighs around 1,200 tons.

And in 2014, excavators uncovered a third megalith estimated at more than 1,500 tons, making it the single largest stone ever carved by human hands.

These stones surpass the capacity of all modern lifting equipment, including the massive cranes housed in NASA’s Vehicle Assembly Building.

Local legends attempt to explain the stones through folklore, describing giants, divine beings, or supernatural helpers moving the massive blocks.

Such stories reflect the community’s long-standing attempt to rationalize a scale of construction that does not align with known historical methods.

Despite these myths, engineering assessments reveal that moving such stones on level ground would require tens of thousands of laborers, even with modern replica equipment.

Lifting them onto elevated platforms would involve an even greater challenge, one modern engineers still cannot fully model.

Archaeological investigation indicates that the Roman structures visible today were built atop a far older stone platform.

This earlier substructure includes the Trilithon and the giant megalithic retaining walls.

Carbon traces and stratigraphic analysis beneath the Roman layers reveal human presence at the site dating back to the Neolithic era, around 9,000 BCE.

This pushes the earliest occupation of Baalbek far beyond the Roman, Persian, and Phoenician periods traditionally associated with the region.

A major German-Lebanese research collaboration launched in 2004 added further complexity to the chronology.

Excavations documented pottery fragments with cuneiform inscriptions dating to the 6th to 4th centuries BCE, indicating Persian activity long before Roman arrival.

However, the Persian architectural record elsewhere—including sites like Persepolis—does not display construction on anything approaching Baalbek’s scale.

Their stone blocks, typically ranging from 1 to 20 tons, fall far short of Baalbek’s hundreds-ton megaliths.

No ancient Near Eastern civilization has demonstrated the capacity to quarry, transport, and elevate stones of this magnitude.

Another significant development emerged from stone-cutting analysis conducted by German researcher Margarete Van Ess.

She noted that the ancient builders exploited natural fissures within the limestone to detach massive blocks cleanly.

This method appears in other Roman projects such as the Pont du Gard aqueduct, suggesting that Roman engineers understood the technique.

Yet even with this knowledge, the Romans’ most advanced lifting apparatus—the polyspastos crane—could safely lift no more than about 6 tons.

It remains unclear how such techniques could be scaled to handle stones more than one hundred times heavier.

Scientific attempts to replicate ancient transport methods using wooden rollers and earthen ramps have also failed to provide workable models.

Experiments with much smaller stones, such as those conducted during efforts to replicate Stonehenge transport, repeatedly resulted in slippage, instability, or catastrophic tipping when moved uphill.

Scaling these methods to megaliths weighing 1,000 tons or more appears unfeasible with ancient materials.

Evidence from Roman architectural plans etched directly into the stone floors at Baalbek confirms that later builders used sophisticated measurement systems and layout techniques.

These engraved blueprints match the geometry of the surviving temple courtyards and reveal advanced surveying methods.

A comparison with constructions in Jerusalem has shown that certain elements of the podium masonry align closely with Herodian-era building styles.

Despite these connections, the foundational megaliths remain unmatched in size, function, and technique.

Modern archaeology now accepts that Baalbek is a layered site representing thousands of years of occupation.

The Phoenicians dedicated it to Baal and Astarte around 3,200 BCE, constructing an early sanctuary whose outline remains visible beneath the Roman Jupiter temple.

Alexander the Great later renamed the site Heliopolis, “City of the Sun.”

The Romans expanded it into one of the grandest temple complexes in their empire beginning around 16 BCE under Augustus.

They built colossal columns, vast courtyards, and monumental staircases—but the Roman contributions sit atop a platform whose origins they did not document.

Later cultures continued to repurpose the site.

Byzantine Christians converted the temples into churches during the 4th and 5th centuries CE.

Arab dynasties transformed the region into the fortified citadel known as Qalaat Baalbek after 637 CE.

Each layer added architecture, but none altered the original megalithic base.

The stones endured through earthquakes, invasions, and rebuilding efforts across more than 11,000 years.

The unresolved question remains at the center of ongoing research: who carved, transported, and positioned stones of such scale?

No civilization documented in the region possessed machinery capable of lifting 800- to 1,500-ton blocks.

No text describes the methods used to achieve this unprecedented engineering feat.

And no parallel structure anywhere else in the ancient world demonstrates a comparable combination of size, precision, and elevation.

Baalbek therefore occupies a unique position in archaeological discourse.

It is simultaneously a Roman temple, a Phoenician sanctuary, a Persian-era settlement, and a prehistoric occupation site.

Its foundation stones exceed the engineering capacity of every culture known to have lived there.

Whether the result of a now-lost building tradition or a still-unidentified earlier culture, the megalithic platform challenges conventional assumptions about ancient technological limits.

As excavations continue, Baalbek remains one of the most enigmatic architectural sites on Earth.

It offers a rare intersection where archaeology, mythology, engineering, and speculative history converge.

Whether explained by forgotten ingenuity or an unrecorded civilization, the presence of stones that modern cranes cannot move ensures that Baalbek will remain central to debates about the true capabilities of the ancient world.

News

Princess Leonor and Lamine Yamal Caught Dining Together in Madrid—Is There a Secret Relationship?

LAMINE YAMAL SURPRISED HAVING DINNER WITH PRINCESS LEONOR! Incredible! Princess Leonor and footballer Lamine Yamal have been spotted dining together…

🚨🔥 “Hey, 18-Year-Old, Shut Your Mouth!” Arda Güler’s Fierce Comeback Sparks Global Frenzy After Yamal’s Insults!

In a dramatic turn of events that has sent shockwaves through the football world, Real Madrid’s young prodigy Arda Güler…

“Inside Lamine Yamal’s Secret World: The Untold Story No One Dared to Reveal!”

Everyone knows how talented Lamine Yamal is on the pitch. The young FC Barcelona prodigy is already making history with…

“Messi’s Shocking Prison Visit to Robinho—What Happened Behind Bars Left Everyone Stunned!”

Just days after lifting another trophy with Inter Miami and being honored as a global ambassador of football, Lionel Messi…

“Isak’s Injury Sparks Unimaginable Chaos: The Unseen Consequences for Liverpool!”

The Impact of Isak’s Injury on Liverpool’s Hopes for the Season Liverpool’s recent setback with Isak’s injury has left fans…

“LeBron James Sends Heartfelt Message to Lionel Messi Ahead of Inter Miami & MLS Debut – The Gesture That Captivated Fans! 💬💖

LeBron James Shows Unwavering Support to Lionel Messi Ahead of His Inter Miami MLS Debut As the countdown to Lionel…

End of content

No more pages to load