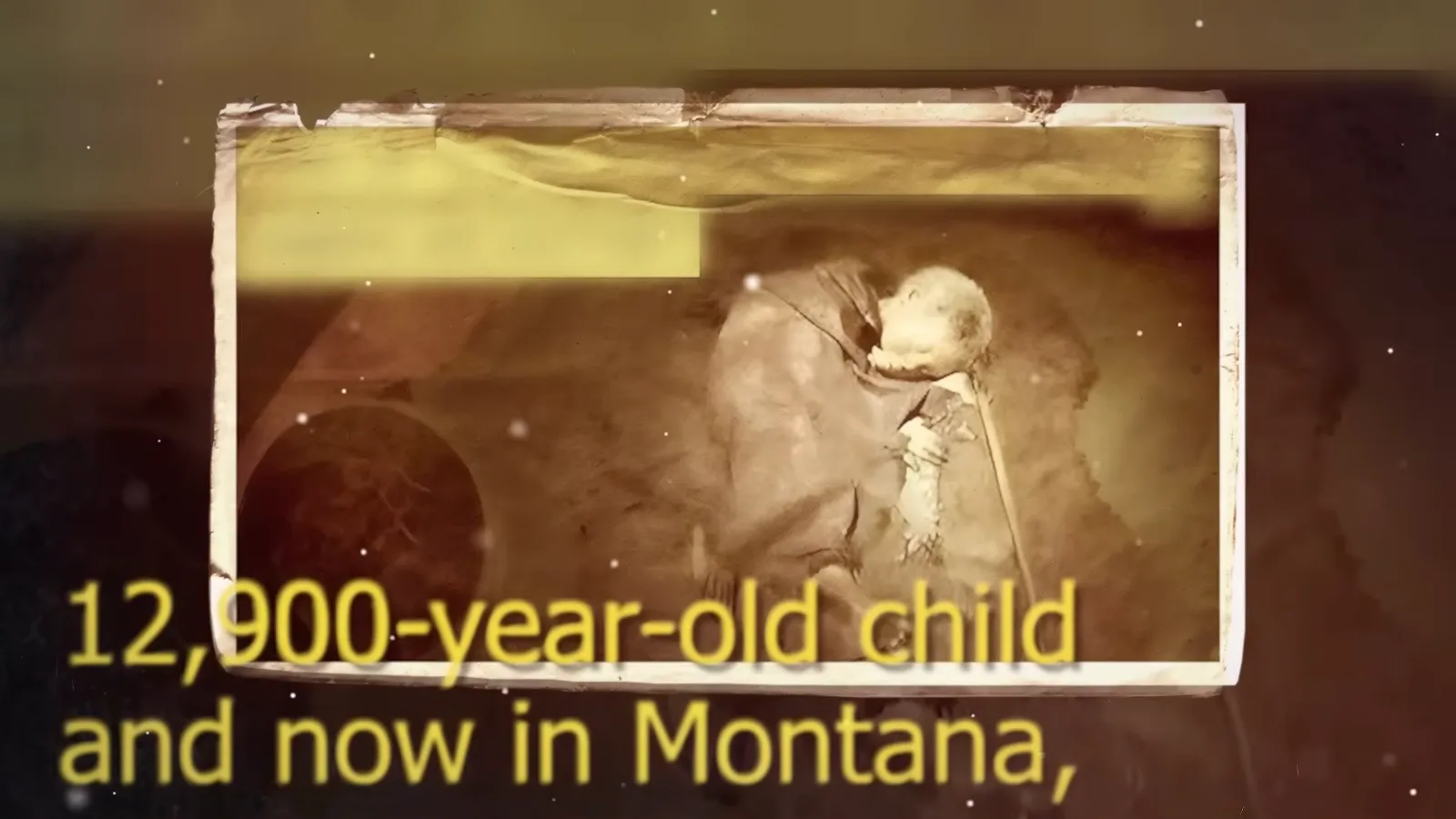

DNA From a 12,900-Year-Old Child in Montana Will Rewrite American History

In a groundbreaking discovery that has the potential to reshape our understanding of the first Americans, scientists have extracted DNA from the remains of a child buried in Montana over 12,000 years ago.

This child’s story, along with the artifacts found alongside them, offers not only a glimpse into the past but also challenges long-held theories about the migration and settlement of ancient peoples in North America.

The implications of this discovery extend far beyond the realm of archaeology; they touch upon identity, culture, and the very roots of indigenous peoples across the continent.

The story begins in 1968 when construction workers in central Montana stumbled upon something extraordinary beneath the earth—a burial site containing the remains of a young child, estimated to be around two years old.

The burial was carefully arranged, with stone tools, antler rods, and a generous sprinkling of red ochre placed alongside the child.

Archaeologists quickly recognized the significance of the find; it was not merely an accidental discovery but a deliberate arrangement that hinted at the cultural practices of the people who lived there during the Ice Age.

The artifacts found with the child were characteristic of the Clovis culture, known for its distinctive spear points and advanced hunting tools.

For decades, the Clovis people were considered the earliest inhabitants of North America, and this burial site was seen as a significant connection to their legacy.

However, the true story of the child remained locked within the fragile bones, waiting for the right moment and technology to reveal its secrets.

For over 40 years, the remains were too delicate for DNA extraction.

Early attempts at testing risked damaging the bones, and researchers were cautious about ruining such a unique specimen.

However, advancements in DNA technology eventually opened the door to new possibilities.

With careful planning and innovative techniques, scientists returned to the burial site, now known as the ANZIC site, with hope and determination.

The team successfully extracted enough genetic material to conduct full genome sequencing, marking a monumental achievement in the field of ancient DNA research.

What they uncovered was unprecedented: the oldest complete human genome ever recovered from the Americas.

The anticipation surrounding the results was palpable, as researchers hoped to uncover not just the identity of the child but also insights into the broader narrative of human migration.

When the DNA sequencing results came back, they revealed a startling truth that would challenge prevailing theories about the origins of the first Americans.

Instead of indicating a lost lineage or a separate population, the child’s genome showed direct connections to the ancestors of nearly all indigenous peoples in the Americas today.

This revelation forced researchers to reconsider the timeline of human migration and the relationships between ancient populations.

Previously, the dominant narrative suggested that the Clovis culture represented a distinct wave of migration into North America.

However, the DNA evidence indicated that these early inhabitants were not outsiders but rather part of a continuous lineage that connected them to modern Native American populations.

This discovery not only rewrote the history books but also reinforced the cultural memory of Indigenous communities, who have long maintained that their roots in the Americas extend far back into the land.

The implications of this discovery are profound.

It challenges the notion that the first Americans were a single group that migrated through a narrow corridor after the Ice Age.

Instead, it suggests a more complex picture of migration, with multiple waves of movement and adaptation occurring over thousands of years.

The genetic connections revealed by the child’s DNA indicate that these early populations were not static but dynamic, continually evolving and spreading across the continent.

The findings also raise important questions about how these ancient families lived, interacted, and adapted to their environments.

The child’s burial, adorned with red ochre and accompanied by tools, suggests that these early peoples had a rich cultural life, complete with rituals and a deep respect for their dead.

This challenges the stereotype of prehistoric humans as primitive and highlights their emotional depth and social complexity.

To understand the context of the Montana child’s life, we must envision the world they inhabited.

The late Ice Age was characterized by vast open grasslands, scattered forests, and an abundance of wildlife.

Mammoths, bison, and ancient horses roamed the landscape, providing sustenance for the early inhabitants.

These were not primitive wanderers but skilled hunters and gatherers, adept at navigating their environment and utilizing its resources.

The presence of sophisticated tools, like the Clovis points found with the child, indicates that these early peoples were highly skilled craftsmen.

They created tools not just for survival but also for art and expression.

The act of crafting a tool required knowledge, patience, and creativity, reflecting the ingenuity of the people who lived during this time.

Family and community were central to their way of life.

Small groups of 20 to 50 people likely formed tight-knit communities, sharing responsibilities and resources.

They moved with the seasons, following animal migrations and adapting to the changing landscape.

This dynamic lifestyle fostered a deep connection to the land and each other, creating a rich tapestry of culture and tradition.

The Montana child’s DNA serves as a bridge connecting the past to the present.

By revealing genetic ties to modern indigenous populations, the discovery underscores the continuity of life and culture in the Americas.

The child’s genome not only reinforces the idea that these early inhabitants were the ancestors of today’s Native Americans but also highlights the complexity of their migration patterns.

As researchers delve deeper into the genetic data, they uncover a more nuanced understanding of how these ancient families spread across the continent.

The findings suggest that migration was not a linear process but rather a series of movements, adaptations, and interactions among diverse groups.

This perspective challenges the traditional view of migration and emphasizes the importance of understanding the interconnectedness of human history.

For many Native American tribes involved in the research, the findings resonate deeply with their cultural narratives.

For generations, indigenous communities have passed down stories of their origins, emphasizing their connection to the land and their ancestors.

The DNA results validate these stories, reinforcing the idea that their roots in the Americas run far deeper than previously acknowledged.

This recognition is crucial for indigenous peoples, who have often faced marginalization and erasure in historical narratives.

By acknowledging the continuity of their ancestry, the scientific community helps to reclaim the history of these communities and honor their contributions to the rich tapestry of American culture.

The discovery of the Montana child’s DNA opens up new avenues for research and exploration.

Scientists are eager to investigate further, aiming to uncover more about the lives of these early inhabitants and their interactions with the environment.

The focus will likely shift to understanding how these ancient populations adapted to changing climates, resources, and landscapes.

Moreover, the findings challenge researchers to rethink existing theories about migration and settlement patterns.

As more ancient genomes are sequenced, the potential for discovering new connections and insights into human history expands.

The Montana child’s legacy will undoubtedly continue to shape the field of archaeology and genetics for years to come.

The story of the 12,900-year-old child from Montana is a testament to the resilience of ancient peoples and their enduring legacy.

Through the lens of DNA, we glimpse a world filled with complexity, culture, and connection.

This discovery not only rewrites the history of the first Americans but also honors the rich traditions and identities of indigenous peoples today.

As we continue to explore the past, we must remember that history is not just a series of events but a tapestry woven from the lives, struggles, and triumphs of countless individuals.

The Montana child stands as a reminder of our shared humanity and the interconnectedness of all people throughout time.

In understanding our origins, we gain insight into who we are today and the paths that lie ahead.

News

Blake Lively: The Media Manipulation Behind Her Trader Joe’s Photo Op

Blake Lively: The Media Manipulation Behind Her Trader Joe’s Photo Op In the ever-watchful gaze of the media, celebrities often…

Blake Lively vs. Justin Baldoni: The Dramatic Legal Showdown Unveiled!

Blake Lively vs. Justin Baldoni: The Dramatic Legal Showdown Unveiled! In the glitzy and often tumultuous world of Hollywood, where fame…

Kodi Lee: The Inspiring Journey of a Musical Sensation After “America’s Got Talent”

Kodi Lee: The Inspiring Journey of a Musical Sensation After “America’s Got Talent” In the world of talent shows, few…

AGT Golden Buzzer Hero Avery Dixon EXPOSES the Truth Behind His Heartbreaking Finale Snub!

AGT Golden Buzzer Hero Avery Dixon EXPOSES the Truth Behind His Heartbreaking Finale Snub! Avery Dixon, the talented saxophonist who…

Where is Sara James from ‘The Voice Kids’ and ‘America’s Got Talent’ Today?

Where is Sara James from ‘The Voice Kids’ and ‘America’s Got Talent’ Today? Sara James, the talented young singer from…

Jay-Z Reportedly Warns Nicki Minaj Not to Involve Beyoncé in Remy Ma Beef

Jay-Z Reportedly Warns Nicki Minaj Not to Involve Beyoncé in Remy Ma Beef In the often tumultuous world of hip-hop,…

End of content

No more pages to load