When Einstein joked about the infinity of human stupidity, he probably didn’t expect his comment to echo across a century of cosmic confusion.

But in truth, his uncertainty about the universe has aged surprisingly well.

Even today — with telescopes powerful enough to see across 13.

5 billion years — the cosmos remains a riddle wrapped in a paradox, hidden inside a force we barely understand.

We’ve mapped galaxies, weighed stars, and studied the glow of the Big Bang.

Yet the answers we find only create deeper questions.

The most unsettling of these is dark energy — the invisible something that accelerates the universe’s expansion, pushing galaxies farther apart in every direction.

To understand how we uncovered this mystery, we have to begin with a much older puzzle: figuring out what the universe even looks like.

A hundred years ago, astronomers believed everything in existence belonged to a single island: the Milky Way.

The idea of other galaxies — vast universes of their own — wasn’t widely accepted.

But the moment we learned to measure distance in space, everything changed.

We first used the simplest trick available: parallax.

As Earth orbits the Sun, stars appear to shift against the distant background.

That angular wiggle, multiplied by the known width of Earth’s orbit, lets us triangulate distance using basic trigonometry.

But parallax only works for stars within a few hundred light years — a tiny bubble compared to the scale of the cosmos.

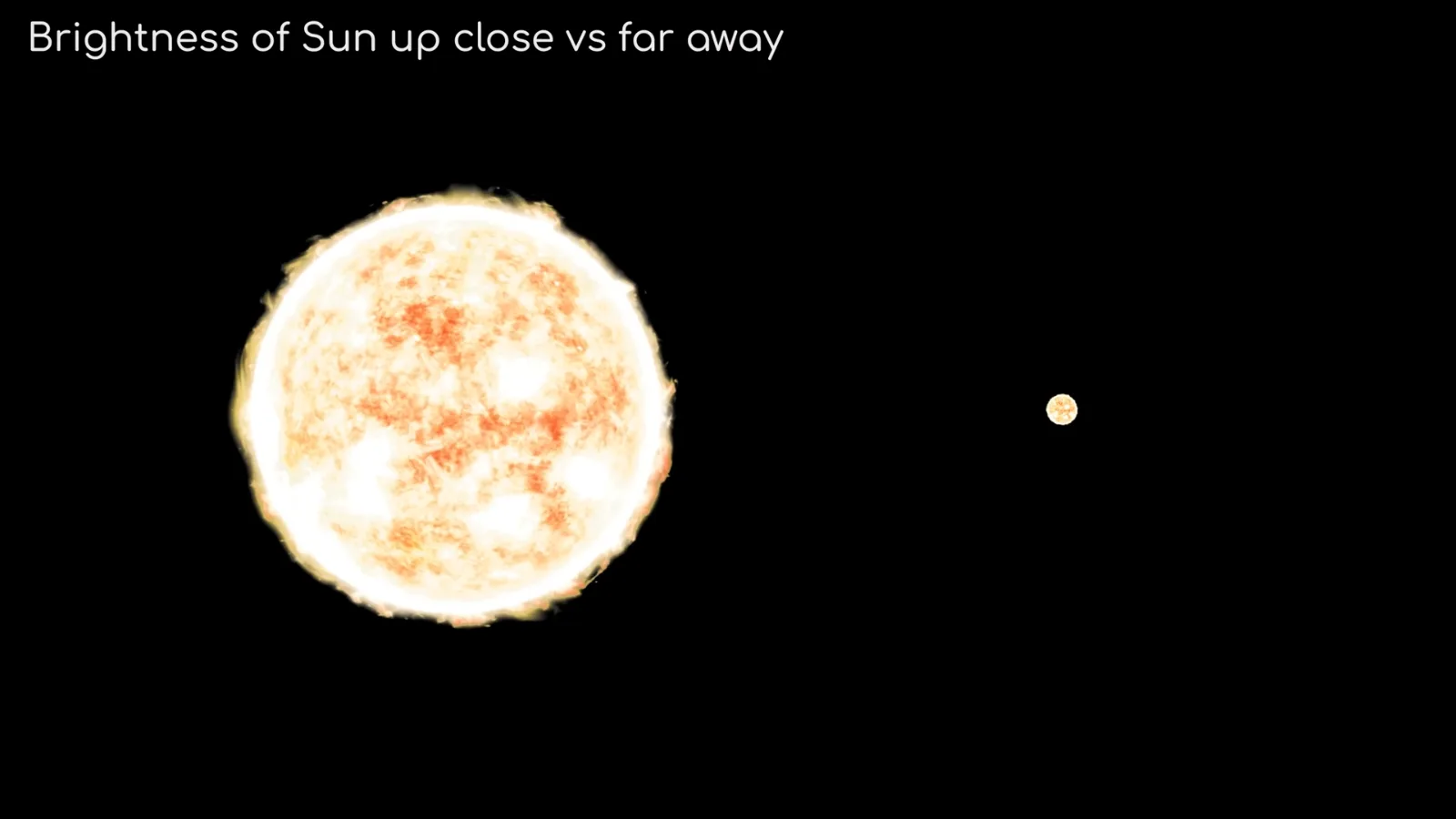

To probe farther, scientists discovered that stars obey patterns.

Main-sequence stars fall along a predictable curve linking temperature, color, and brightness.

If we know a star’s color, we know its true brightness — and by comparing it to how dim it appears, we can estimate its distance.

It’s less precise than parallax, but far more wide-reaching.

Still, we needed something brighter — something so powerful it could bridge the gulf between galaxies.

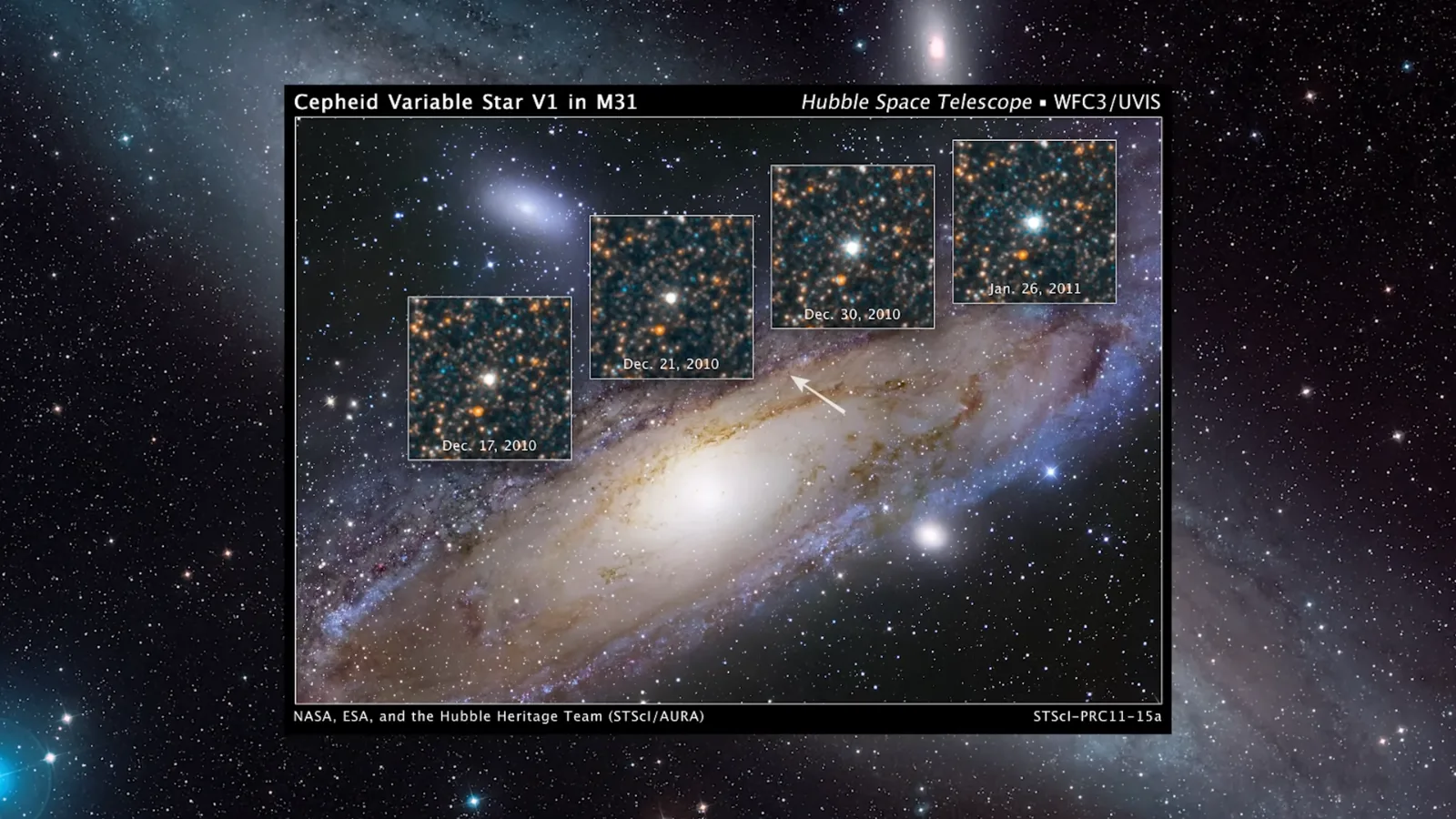

Enter Cepheid variables, whose rhythmic pulsing encodes their intrinsic luminosity.

Henrietta Swan Leavitt discovered this relationship; Edwin Hubble used it to measure the distance to the Andromeda “nebula.

” What he found shocked the world: Andromeda was far too distant to be part of the Milky Way.

It was its own galaxy.

Then came the second shock.

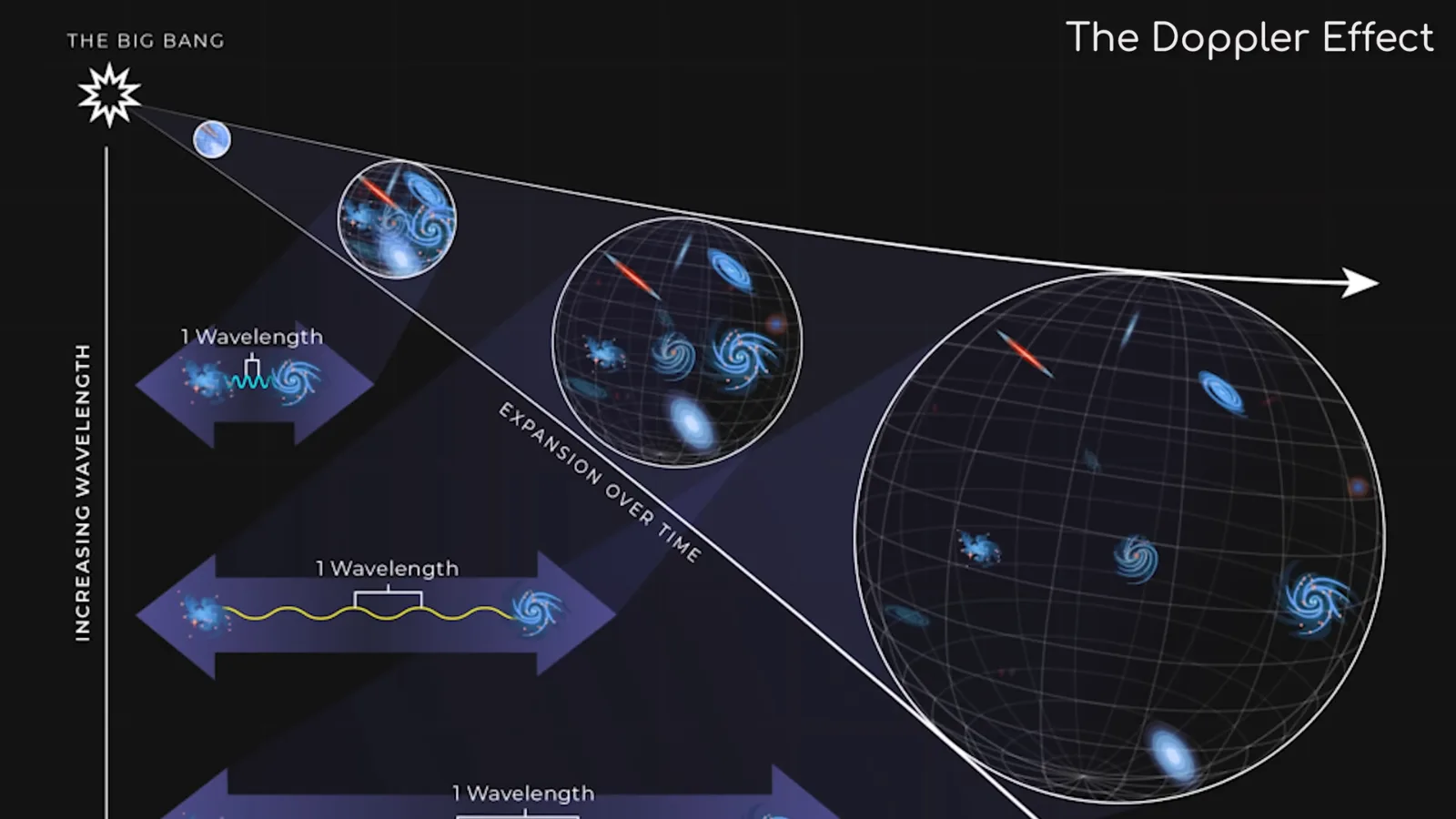

Observing the Doppler shift of distant galaxies, Hubble realized almost every one was moving away from us — the universe was expanding.

Einstein resisted the idea at first, even adding the infamous cosmological constant to “fix” his equations.

Only later did he admit it was his greatest blunder.

Yet the expanding universe raised enormous new questions.

Why is the night sky dark — a puzzle known as Olbers’ Paradox? In an infinite, static universe, every patch of sky should blaze as bright as a star’s surface.

But the sky is black because the universe has a beginning, and because galaxies beyond a certain distance are receding faster than light can reach us.

This boundary defines our observable universe, a sphere determined not by what exists, but by what we can see.

As astronomers probed deeper, they confronted troubling anomalies.

Matter wasn’t behaving the way gravity predicted.

Galaxies rotated too fast; clusters held too tightly.

Something invisible — dark matter — had to be adding mass we couldn’t detect.

And even stranger: galaxies were accelerating away from each other.

Expansion wasn’t slowing as gravity stretched thinner.

It was speeding up.

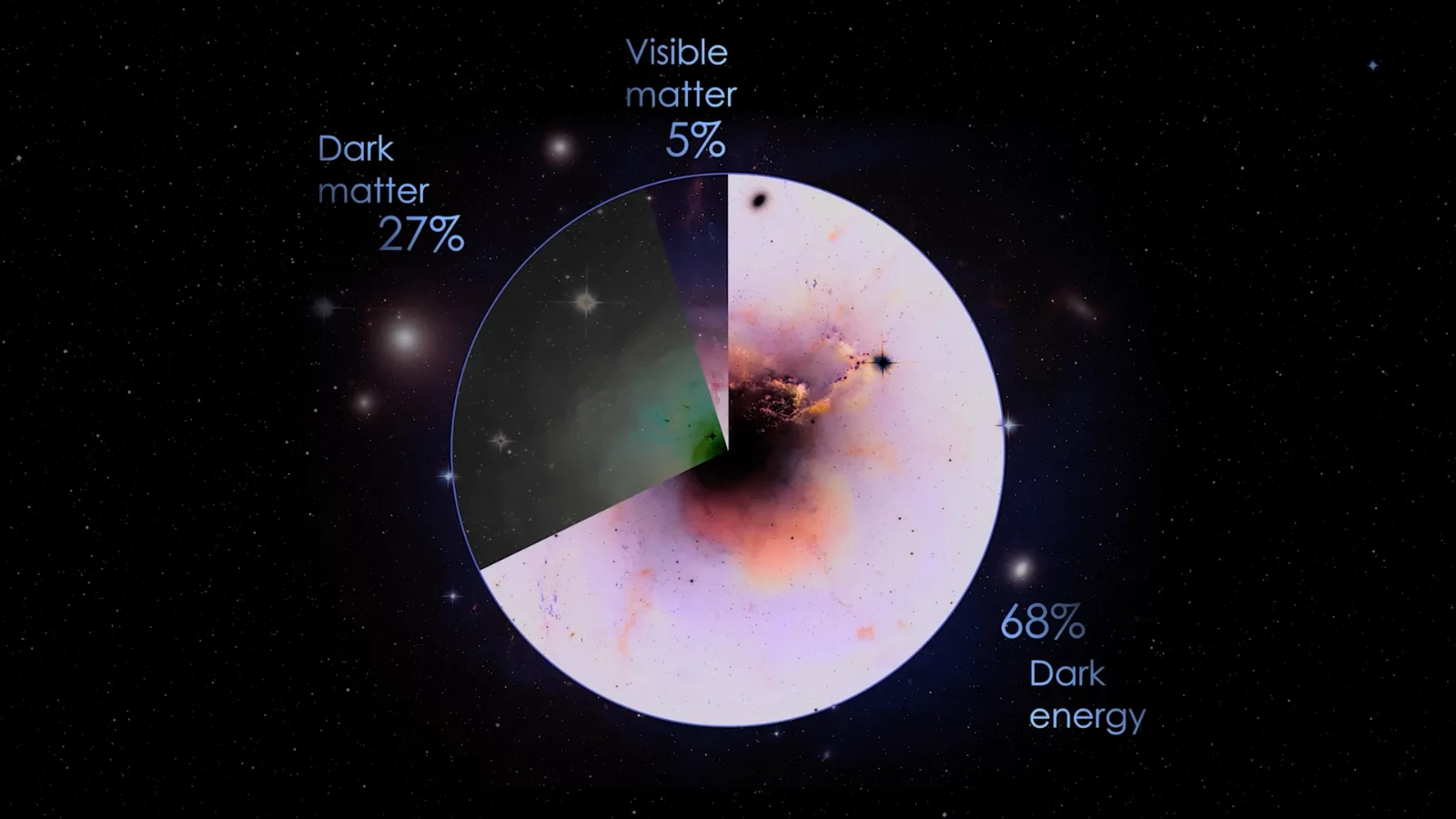

To account for this, scientists introduced dark energy, the substance or field that makes up 68% of everything — yet interacts with none of our instruments.

It was the return of Einstein’s cosmological constant, except now reinterpreted as a property of space itself.

Empty vacuum, it seemed, might not be empty at all.

Quantum mechanics offered one explanation: virtual particles, popping in and out of existence, could provide outward pressure.

But when physicists tried to compute the expected energy of this quantum vacuum, the answer exceeded reality by 120 orders of magnitude — the single worst prediction in modern physics.

So theorists introduced another idea: quintessence, a fifth fundamental force represented by a field that changes over time.

But the more possibilities we added, the more confusing the picture became.

To investigate dark energy directly, scientists constructed new instruments.

Brazil’s BINGO telescope examines hydrogen emissions to map matter distribution in cosmic voids.

ESA’s Euclid telescope, launched in 2023, now surveys a third of the sky, capturing visible and infrared light from tens of millions of galaxies to track dark energy’s influence across 10 billion years.

With AI tools sorting its vast dataset, Euclid might soon expose patterns we’ve never seen.

Understanding dark energy isn’t academic — it determines our ultimate fate.

If dark energy is vacuum energy, the universe expands forever, cooling into a lonely wasteland — the Big Freeze.

Stars die, black holes evaporate, and entropy reigns.

Roger Penrose suggests this “heat death” could actually seed the next Big Bang, linking cosmic cycles like beads on an infinite chain.

But the vacuum might not be stable.

If it’s meta-stable, the universe could tunnel into a lower-energy state via quantum decay — erasing atoms, stars, and even physical laws in an instant.

If dark energy is a dynamic field, the possibilities multiply.

If it weakens, expansion might slow; the universe could drift into a calmer heat death.

If it reverses, gravity may take over — the universe collapses in a Big Crunch.

Or worst of all:

If dark energy grows stronger over time, we face the Big Rip, where galaxies, stars, planets, molecules, and atoms are torn apart as space itself stretches infinitely in a finite period.

Other models propose cyclical universes linked by Big Bounces, where contraction rebounds into expansion.

Each cycle rewrites reality anew.

In the end, all these possibilities flow from one unknown:

What is dark energy?

We only know it exists because space is expanding.

We feel its touch only through cosmic motion, not physical sensation.

It fills the universe, shapes its evolution, and determines its destiny — yet remains invisible and untouchable.

But as Euclid, Webb, and next-generation observatories gather more data, we may soon get our first real glimpse of the force that will ultimately dictate how everything ends.

Until then, the universe remains a breathtaking question mark — a puzzle we are still learning to read.

And as strange as it sounds, the fact that we don’t know all the answers is part of what makes the cosmos so extraordinary.

We are small.

The universe is vast.

But we are woven from the same fabric — and wired with the same curiosity — that drives the stars themselves.

News

“Screaming Silence: How I Went from Invisible to Unbreakable in the Face of Family Betrayal”

“You’re absolutely right. I’ll give you all the space you need.” It’s a mother’s worst nightmare—the slow erosion of her…

“From Invisible to Unstoppable: How I Reclaimed My Life After 63 Years of Serving Everyone Else”

“I thought I needed their approval, their validation. But the truth is, I only needed myself.” What happens when a…

“When My Son Denied Me His Blood, I Revealed the Secret That Changed Everything: A Journey from Shame to Triumph”

“I thought I needed my son’s blood to save my life. It turned out I’d saved myself years ago, one…

“When My Daughter-in-Law Celebrated My Illness, I Became the Most Powerful Woman in the Room: A Journey of Betrayal, Resilience, and Reclaiming My Life”

“You taught me that dignity isn’t about what people give you, it’s about what you refuse to lose. “ What…

“When My Sister-in-Law’s Christmas Gala Turned into My Liberation: How I Exposed Their Lies and Found My Freedom”

“Merry Christmas, Victoria. ” The moment everything changed was when I decided to stop being invisible. What happens when a…

On My Son’s Wedding Day, I Took Back My Dignity: How I Turned Betrayal into a Legacy

“You were always somebody, sweetheart. You just forgot for a little while.” It was supposed to be the happiest day…

End of content

No more pages to load