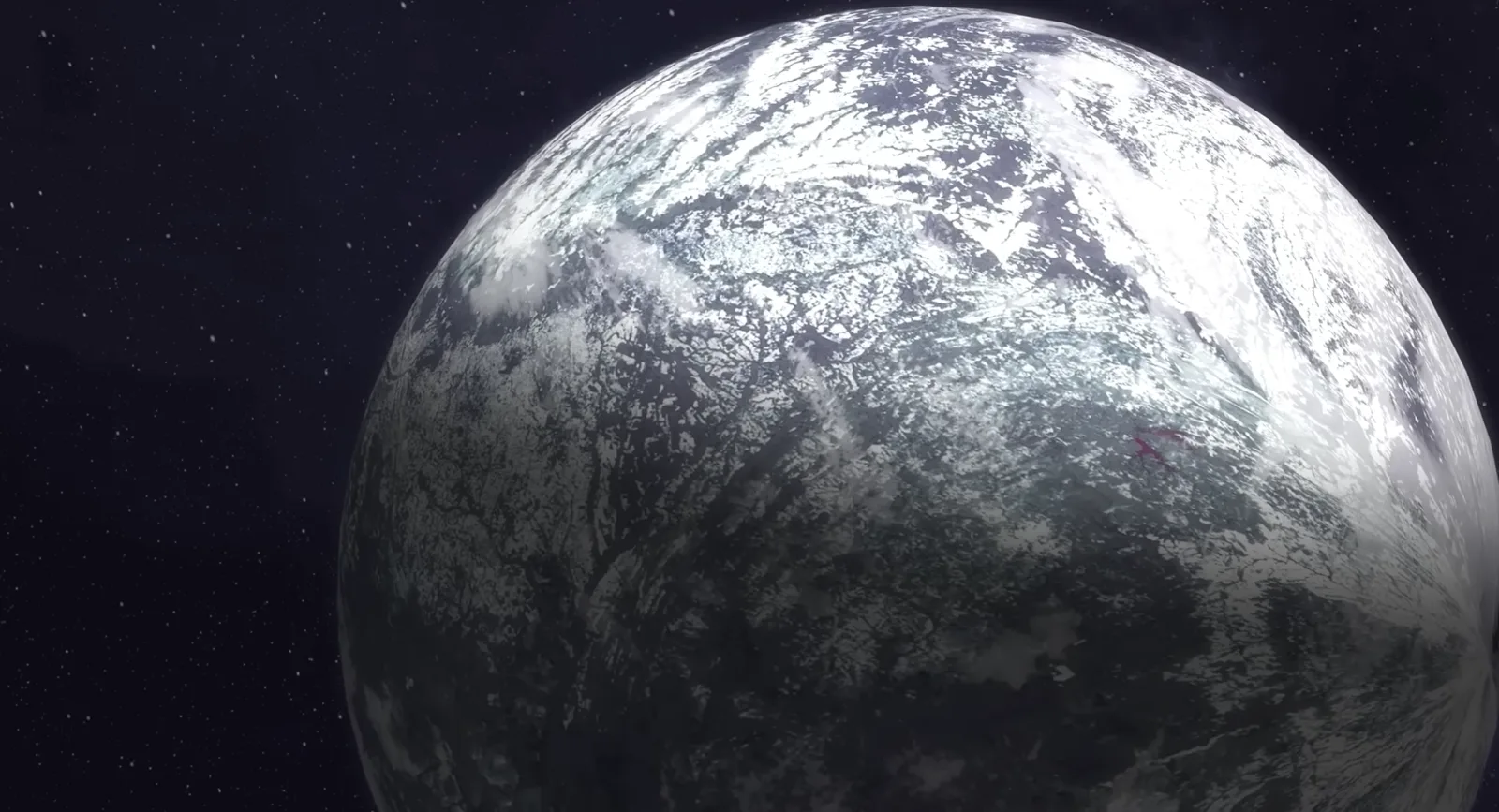

Imagine a planet that could be the perfect second Earth—an exoplanet orbiting the closest star to us, Proxima Centauri.

It’s a tantalizing thought, but is it truly possible? In 2025, astronomers revealed some groundbreaking discoveries about this distant star system and its Earth-like planets.

While one planet might have the potential for life, another discovery could challenge everything we think we know about exoplanet formation.

The more we learn about these distant worlds, the more questions arise.

Could one of them be humanity’s new home? Or will the truth shatter our expectations?

When we think about finding another Earth, the excitement often centers on the idea of planets existing somewhere out there, just waiting to be discovered.

But what if we told you the search is no longer a distant dream? In 2025, a set of exciting new findings have brought us closer than ever to identifying our future home among the stars.

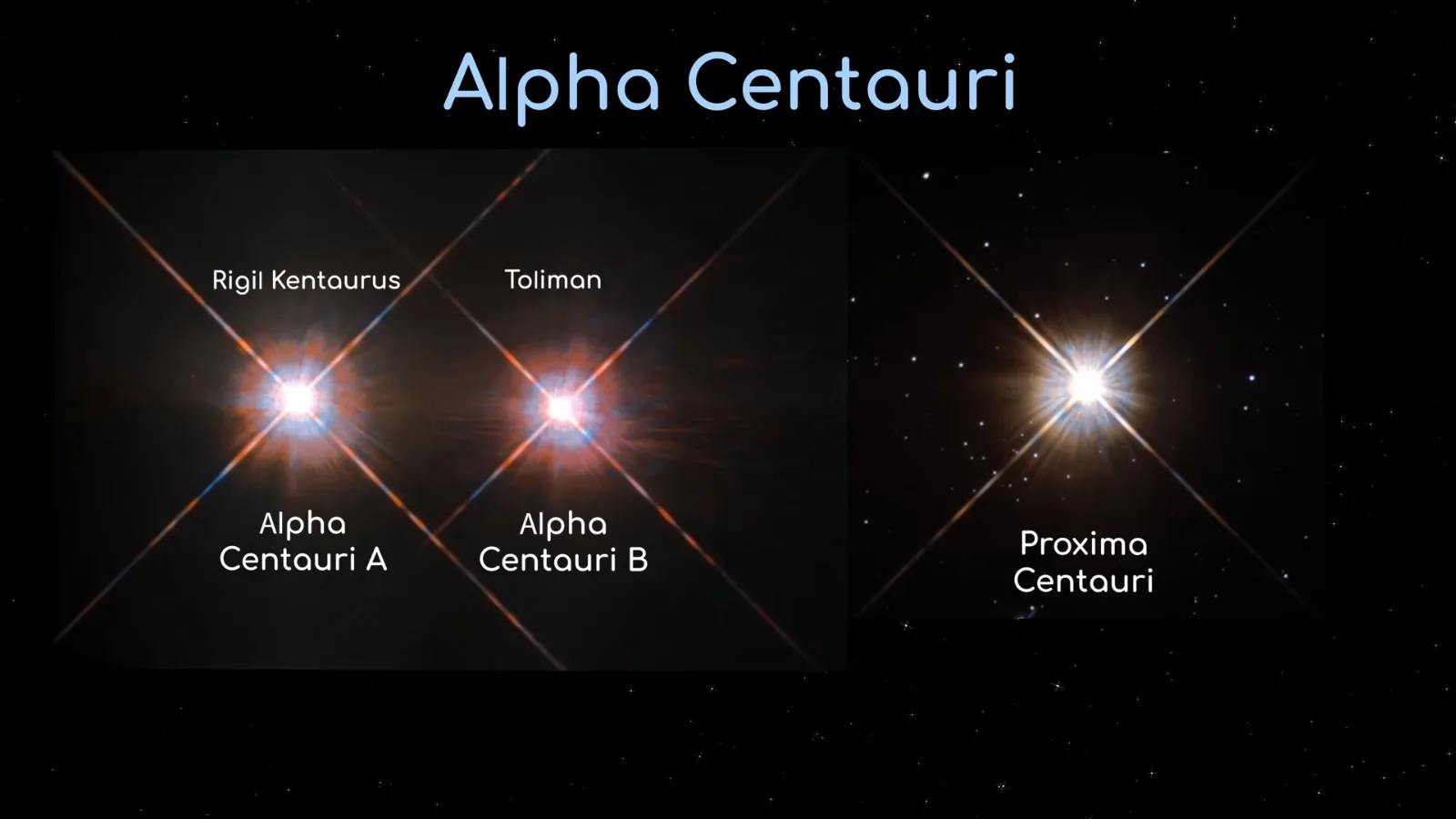

Astronomers have been zeroing in on Proxima Centauri, the closest known star to our solar system, located just 4.2 light years away.

Proxima Centauri has been in the spotlight for years, but it wasn’t until recent discoveries that the potential for habitability became a focal point.

Proxima Centauri is a red dwarf star, and around it orbits at least two exoplanets—Proxima Centauri B and Proxima D. Proxima Centauri B, the first discovered in 2016, has become one of the most discussed candidates for finding life outside our solar system.

It is in the habitable zone of its star—an area where liquid water might exist on its surface, which is one of the key ingredients for life as we know it.

While that sounds promising, there’s more to the story.

Despite its close proximity to its star, Proxima Centauri B could be a hostile environment.

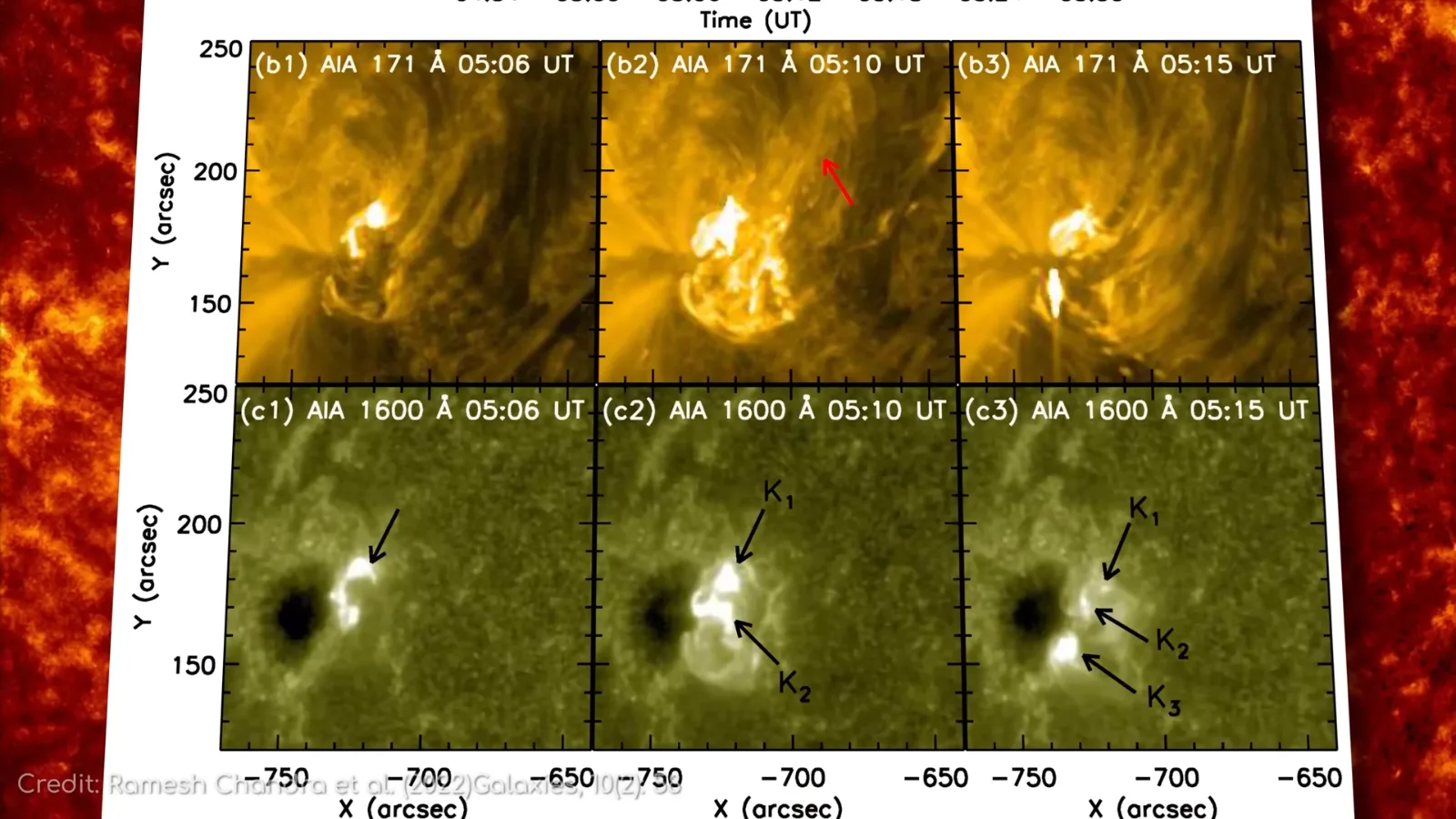

The star itself is highly active, emitting intense solar flares and X-rays that could bombard the planet with radiation levels far higher than we experience on Earth.

This raises a crucial question: can life exist in such extreme conditions? While scientists are hopeful, the intense radiation could strip away any atmosphere the planet might have, making it far less hospitable.

The planet’s rotation could also be problematic.

Being tidally locked to its star, one side would always face the sun, leaving the other in eternal darkness.

This could create extreme temperature variations between the two sides, making it difficult for any potential life to thrive.

Then, in 2022, came the discovery of another planet in the Proxima Centauri system: Proxima D.

Although much smaller than Proxima Centauri B, this planet has stirred up its own set of debates among astronomers.

Located much closer to its star, Proxima D has an incredibly short orbit—just 5.1 Earth days.

But with temperatures likely soaring up to 87°C (188°F), it is far from being an ideal candidate for life.

However, the discovery of Proxima D wasn’t all bad news.

This planet, along with Proxima Centauri B, forms part of a larger puzzle in understanding how exoplanets form and evolve.

Proxima D could help us unlock answers about planetary systems and the conditions under which planets like Earth could form around red dwarf stars.

Yet, Proxima D’s potential for habitability seems slim, primarily due to the intense radiation and its close proximity to its star.

Still, the idea that a nearby star could host not just one but two potentially habitable planets is revolutionary.

But these discoveries also highlight the difficulty of finding planets that could truly support life.

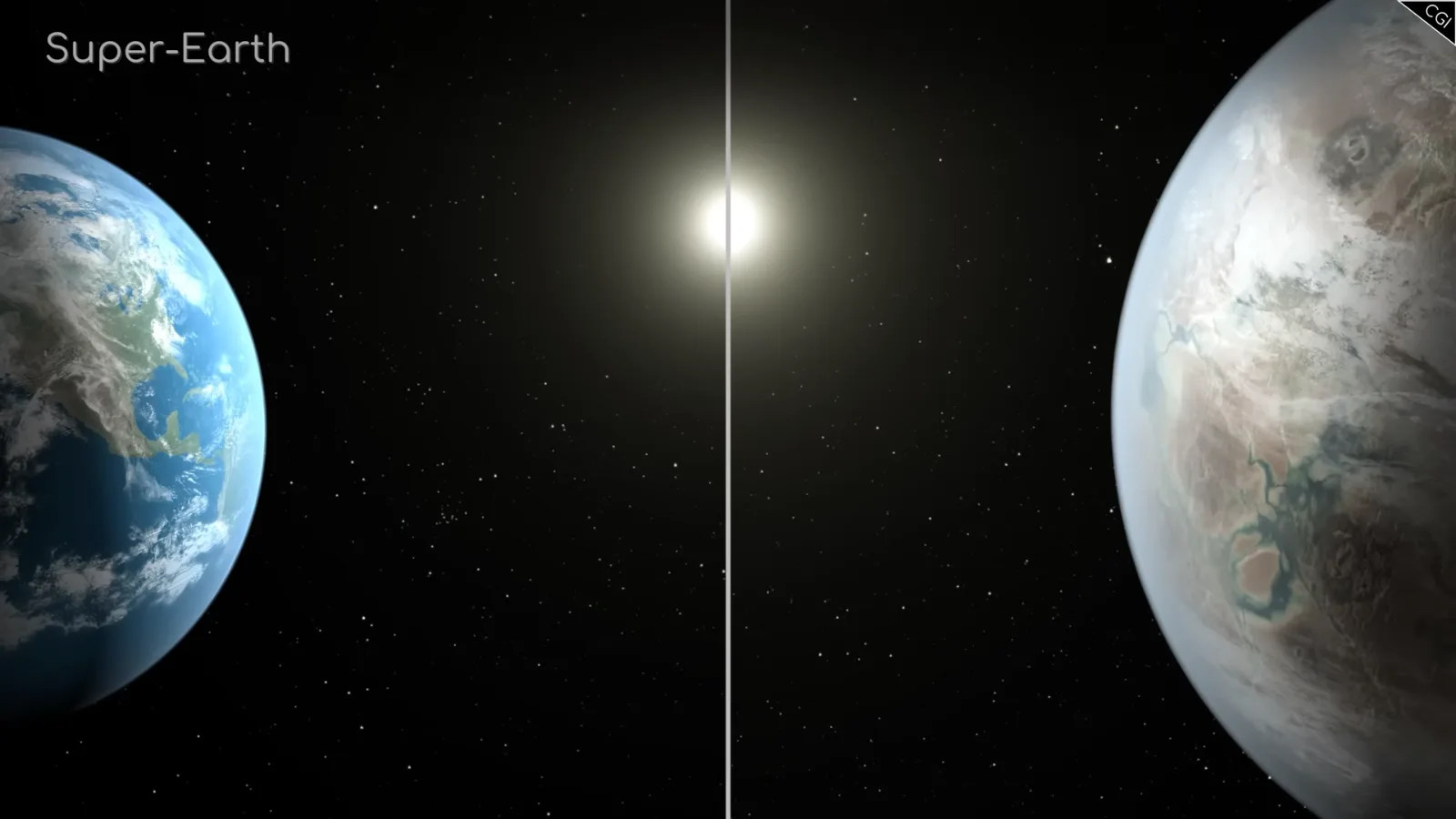

As astronomers continue to search for Earth-like planets, many of the ones they find are under challenging conditions—either too hot, too cold, or exposed to dangerous radiation.

And even though the term “Earth 2.0” is often thrown around, the reality is that finding a perfect replica of Earth might not be as easy as it sounds.

One of the key challenges in studying exoplanets lies in the stars they orbit.

Proxima Centauri is a red dwarf star, which, unlike our Sun, burns much cooler and longer.

Red dwarfs make up about 75% of all stars in the Milky Way galaxy, and most exoplanets we’ve discovered orbit these types of stars.

But there’s a downside to living near a red dwarf.

They emit significantly more radiation than our Sun, which can be catastrophic for planets in their habitable zones.

Even if a planet is at the right distance, the radiation could make the surface uninhabitable, wiping out any chance for life to develop.

In fact, it’s not just the planets that are an issue— it’s the solar radiation from their stars.

Proxima Centauri, in particular, is known for its powerful flares, which occur at a much higher frequency and intensity than those from our Sun.

These flares could bomb any atmosphere with dangerous amounts of UV radiation and X-rays.

While some scientists believe that life could still survive in certain niches or underground, the overall habitability of planets like Proxima Centauri B remains in question.

Despite the challenges, we have new tools at our disposal to study these far-off worlds.

Telescopes like the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) and TESS (Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite) are providing us with the most detailed information about exoplanets yet.

JWST, launched in late 2021, is capable of studying exoplanet atmospheres and determining whether conditions exist that could support life.

As we learn more about the composition of distant planets, we’ll get closer to understanding if any of them can truly be called “Earth 2.0.”

However, even with the incredible progress in astronomy, space travel to these distant stars remains a far-off dream.

The idea of sending a probe to Proxima Centauri, for example, would take thousands of years with current propulsion technology.

But there is hope on the horizon with projects like Breakthrough Starshot, which aims to send microprobes to Alpha Centauri—our closest stellar system—at 15-20% of the speed of light.

If successful, this could open the door to exploring the exoplanets around Proxima Centauri in ways we’ve never been able to before.

As we continue to discover new planets, one thing is certain: the search for “Earth 2.0” is far from over.

With every new discovery, we get closer to understanding how planets form, how they evolve, and whether any of them can sustain life.

Yet the more we uncover, the more we realize how unlikely it is that we’ll find an exact replica of Earth.

What we need to focus on instead is how to make life sustainable on the planets we can reach—whether they’re similar to Earth or completely alien in nature.

News

“Screaming Silence: How I Went from Invisible to Unbreakable in the Face of Family Betrayal”

“You’re absolutely right. I’ll give you all the space you need.” It’s a mother’s worst nightmare—the slow erosion of her…

“From Invisible to Unstoppable: How I Reclaimed My Life After 63 Years of Serving Everyone Else”

“I thought I needed their approval, their validation. But the truth is, I only needed myself.” What happens when a…

“When My Son Denied Me His Blood, I Revealed the Secret That Changed Everything: A Journey from Shame to Triumph”

“I thought I needed my son’s blood to save my life. It turned out I’d saved myself years ago, one…

“When My Daughter-in-Law Celebrated My Illness, I Became the Most Powerful Woman in the Room: A Journey of Betrayal, Resilience, and Reclaiming My Life”

“You taught me that dignity isn’t about what people give you, it’s about what you refuse to lose. “ What…

“When My Sister-in-Law’s Christmas Gala Turned into My Liberation: How I Exposed Their Lies and Found My Freedom”

“Merry Christmas, Victoria. ” The moment everything changed was when I decided to stop being invisible. What happens when a…

On My Son’s Wedding Day, I Took Back My Dignity: How I Turned Betrayal into a Legacy

“You were always somebody, sweetheart. You just forgot for a little while.” It was supposed to be the happiest day…

End of content

No more pages to load