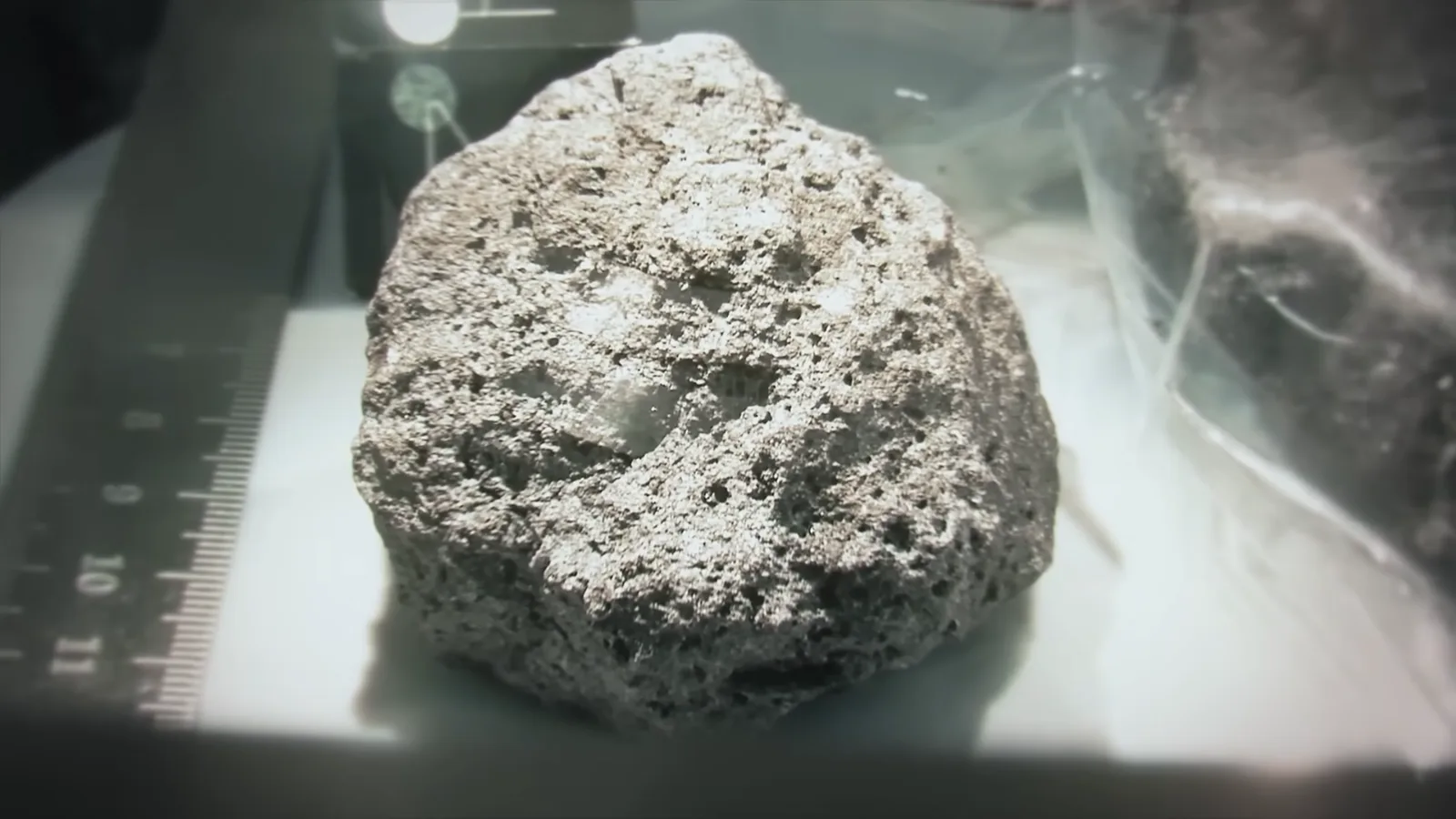

When the Apollo astronauts brought home their precious cargo of lunar rocks, no one expected them to unveil one of the greatest mysteries of Earth’s early history.

Yet hidden in those dusty samples was a clue — molten remnants of catastrophic impacts — all dated to the same narrow window: 4.1 to 3.8 billion years ago.

Instead of a slow, steady cosmic bombardment, the Moon appeared to have endured an extraordinary, violent surge of impacts within a geologically brief moment.

Researchers would later call this dramatic interval the Late Heavy Bombardment (LHB).

But where did this sudden rain of destruction come from? And if the Moon was pounded so brutally… what happened to Earth?

To understand the chaos, we must travel back to the origins of the solar system.

About 4.6 billion years ago, a vast cloud of dust and gas collapsed under gravity, forming the Sun at its center.

Around it, swirling debris collided, merged, and accumulated into planetesimals — the seeds of future planets.

In a mere hundred million years, these clumps of matter grew into the terrestrial worlds: Mercury, Venus, Earth, and Mars.

Earth itself endured a colossal collision during this stage — a Mars-sized body struck our young planet, ejecting molten material that eventually coalesced into our Moon.

After this, the inner solar system began to calm.

Accretion slowed.

The leftover debris thinned.

You would expect impacts to steadily decrease, not spike later.

And yet, lunar samples show something different — a violent resurgence of cosmic shrapnel.

What could cause such a delayed catastrophe?

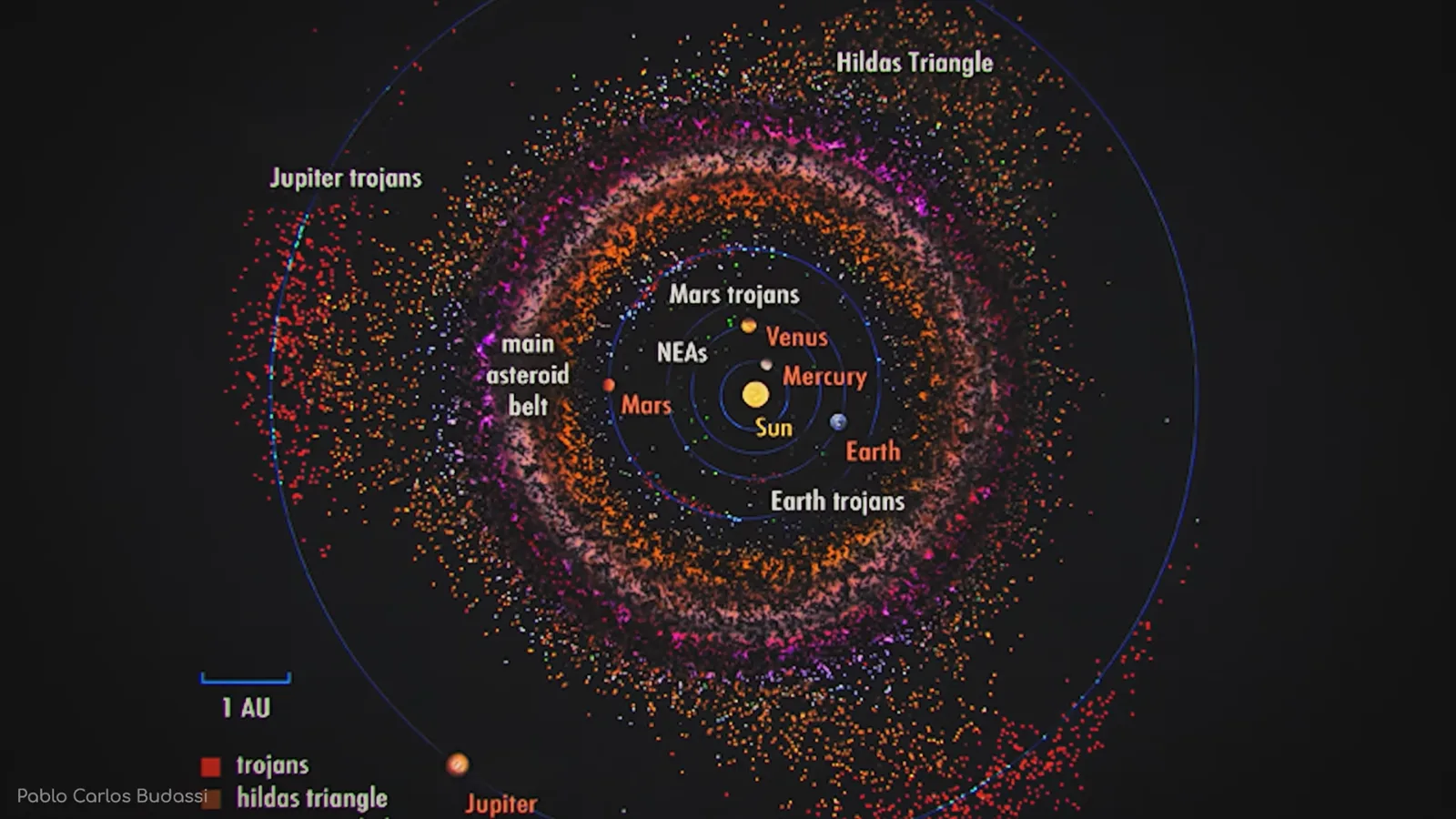

The prime suspect: Jupiter, the solar system’s gravitational juggernaut.

Jupiter didn’t always sit where it does today.

Early in the solar system’s formation, the gas giant likely migrated inward toward the Sun, drawn by the dense gaseous disk surrounding the young star.

When Saturn formed, its gravity interacted with Jupiter’s, halting its inward march and reversing its path.

This gravitational dance — often called the “Grand Tack” model — destabilized countless smaller bodies.

As Jupiter plowed through the primordial asteroid belt, its immense gravity scrambled the orbits of millions of objects.

Most of this debris either spiraled into the Sun or was flung outward… but a significant portion was hurled inward toward the terrestrial planets.

This cosmic shuffle brought in two distinct asteroid populations:

S-type (stony) asteroids from the inner belt

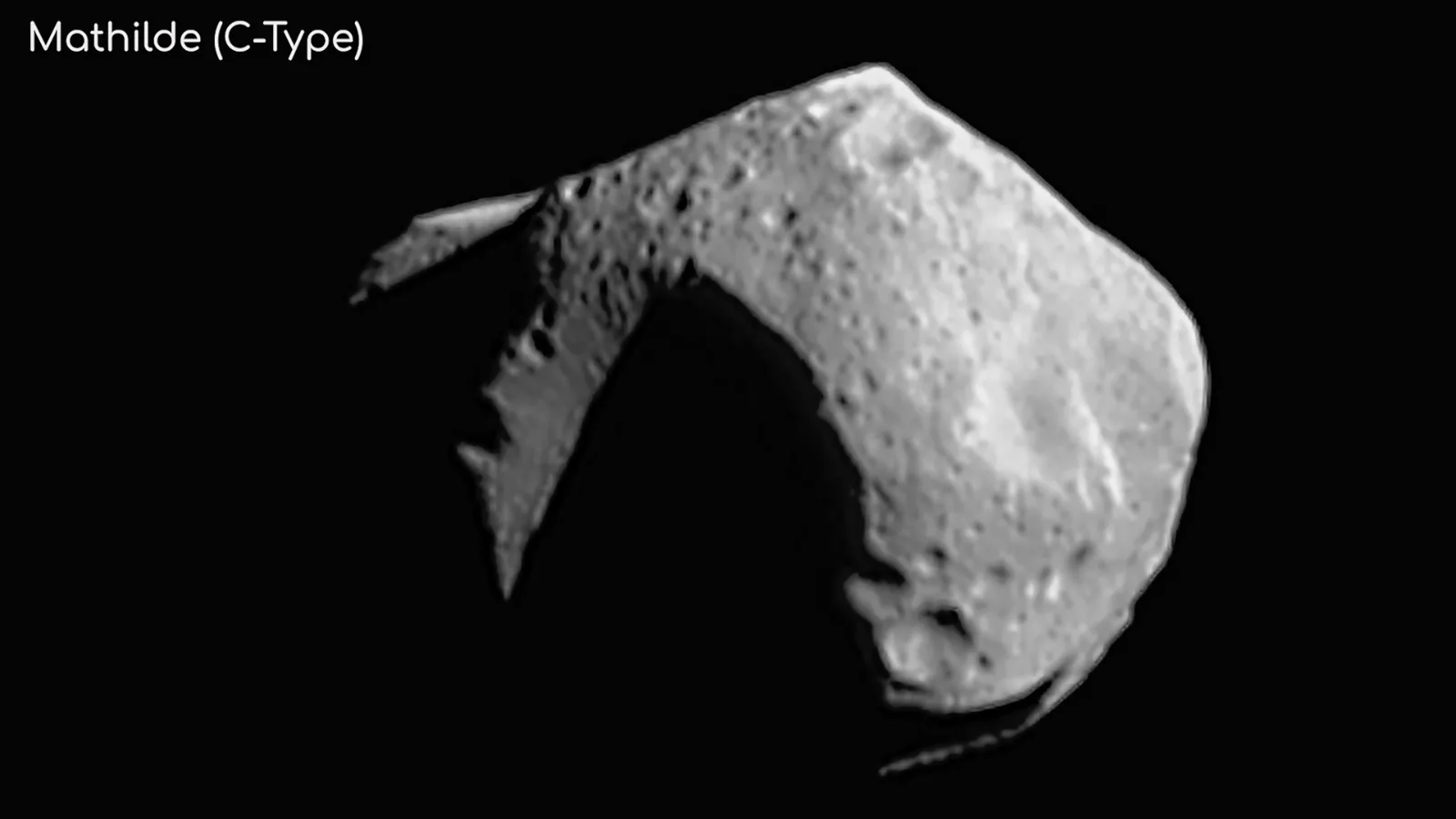

C-type (carbon-rich) asteroids from farther out — crucially, rich in water and complex organic molecules

This detail matters, because the kind of asteroid that struck Earth determines what ingredients arrived with it.

While the Moon was pounded relentlessly, Earth did not escape the onslaught.

It was hit just as fiercely — perhaps even more so — but our planet’s violent geological churn erased all visible traces.

At the time, Earth had recently cooled enough to form a solid crust, but its lithosphere was fragile and constantly recycled by extreme volcanic activity.

Any crater formed by an incoming asteroid would have been swallowed, melted, or dragged beneath the surface in short order.

But although Earth lost its scars, it retained something much more valuable: the materials delivered by these impacts.

Asteroids striking the young Earth deposited enormous amounts of heavy metals like nickel, gold, lead, and copper — materials that would otherwise have sunk deep into Earth’s molten interior.

More importantly, those C-type asteroids delivered vast quantities of water.

If this water had arrived earlier, it would have instantly boiled off into space.

But the timing was perfect: Earth had cooled just enough to hold onto its atmosphere.

Incoming impacts vaporized oceans temporarily, only for them to condense again — a cycle that gradually birthed the seas we know today.

And along with water came something even more astonishing: the building blocks of life.

Recent studies have shown that all five precursor components of DNA and RNA can be found on meteorites.

Tiny molecules from distant regions of the solar system may have seeded Earth during this bombardment, helping form the organic soup from which life emerged.

Geological evidence suggests life appeared on Earth roughly 3.

8 billion years ago — coinciding precisely with the tail end of the Late Heavy Bombardment.

Whether coincidence or catalyst, the overlap is striking.

If life needed water, organics, energy, and chemical complexity to begin, the Late Heavy Bombardment may have provided all four at once.

The Moon serves as our cosmic archive, preserving what Earth lost.

Because the lunar surface has no plate tectonics, no weather, and no erosion, its craters remain virtually unchanged across billions of years.

The smooth, dark maria we see on the Moon formed when enormous impacts cracked the crust, allowing lava to pool and solidify.

These features, widespread and consistent in age, support the idea of an impact surge.

Yet the theory remains debated.

New techniques suggest the bombardment might have been extended rather than sudden.

Some argue that Moon samples reflect only local events, not global patterns.

Future missions — beginning with NASA’s Artemis program — may finally gather samples from lunar far-side regions to settle the question.

Regardless of the precise timeline, one fact remains clear: Earth owes much of its water — and possibly its first life — to asteroids.

Our oceans, our continents, the metals we mine, and perhaps even the spark of biology itself may all be gifts of that chaotic era.

Without the bombardment, Earth might have remained a dry, barren world.

So the next time you watch moonlight shimmer across the sea, consider this: the Moon’s scars are the record of impacts that helped fill our oceans below.

Life on Earth may have begun not in peaceful ponds, but in the aftermath of cosmic fire.

And if that’s true…then every wave that touches our shores is a whisper from the ancient, violent sky.

News

“Screaming Silence: How I Went from Invisible to Unbreakable in the Face of Family Betrayal”

“You’re absolutely right. I’ll give you all the space you need.” It’s a mother’s worst nightmare—the slow erosion of her…

“From Invisible to Unstoppable: How I Reclaimed My Life After 63 Years of Serving Everyone Else”

“I thought I needed their approval, their validation. But the truth is, I only needed myself.” What happens when a…

“When My Son Denied Me His Blood, I Revealed the Secret That Changed Everything: A Journey from Shame to Triumph”

“I thought I needed my son’s blood to save my life. It turned out I’d saved myself years ago, one…

“When My Daughter-in-Law Celebrated My Illness, I Became the Most Powerful Woman in the Room: A Journey of Betrayal, Resilience, and Reclaiming My Life”

“You taught me that dignity isn’t about what people give you, it’s about what you refuse to lose. “ What…

“When My Sister-in-Law’s Christmas Gala Turned into My Liberation: How I Exposed Their Lies and Found My Freedom”

“Merry Christmas, Victoria. ” The moment everything changed was when I decided to stop being invisible. What happens when a…

On My Son’s Wedding Day, I Took Back My Dignity: How I Turned Betrayal into a Legacy

“You were always somebody, sweetheart. You just forgot for a little while.” It was supposed to be the happiest day…

End of content

No more pages to load