“The dead star isn’t just swallowing planets… it’s tearing entire worlds into glowing plasma.”

A single line from NASA’s briefing—one that left even veteran astronomers stunned.

Space is full of wonders, but every now and then, astronomers stumble upon something so shocking that it shakes the foundations of astrophysics.

That’s exactly what happened when NASA’s Chandra X-ray Observatory revealed a gruesome spectacle unfolding 45 light-years away in Pisces.

A white dwarf named G29-38—the collapsed core of a once-sunlike star—is actively devouring its own planets.

White dwarfs are known for their crushing gravity, but scientists had never witnessed one feasting so violently.

The planets around G29-38 are being shredded into incandescent plasma, forming a glowing halo of pulverized worlds.

It is one of the clearest examples yet of stellar cannibalism.

But what’s even more alarming?

Stars don’t always get the last bite.

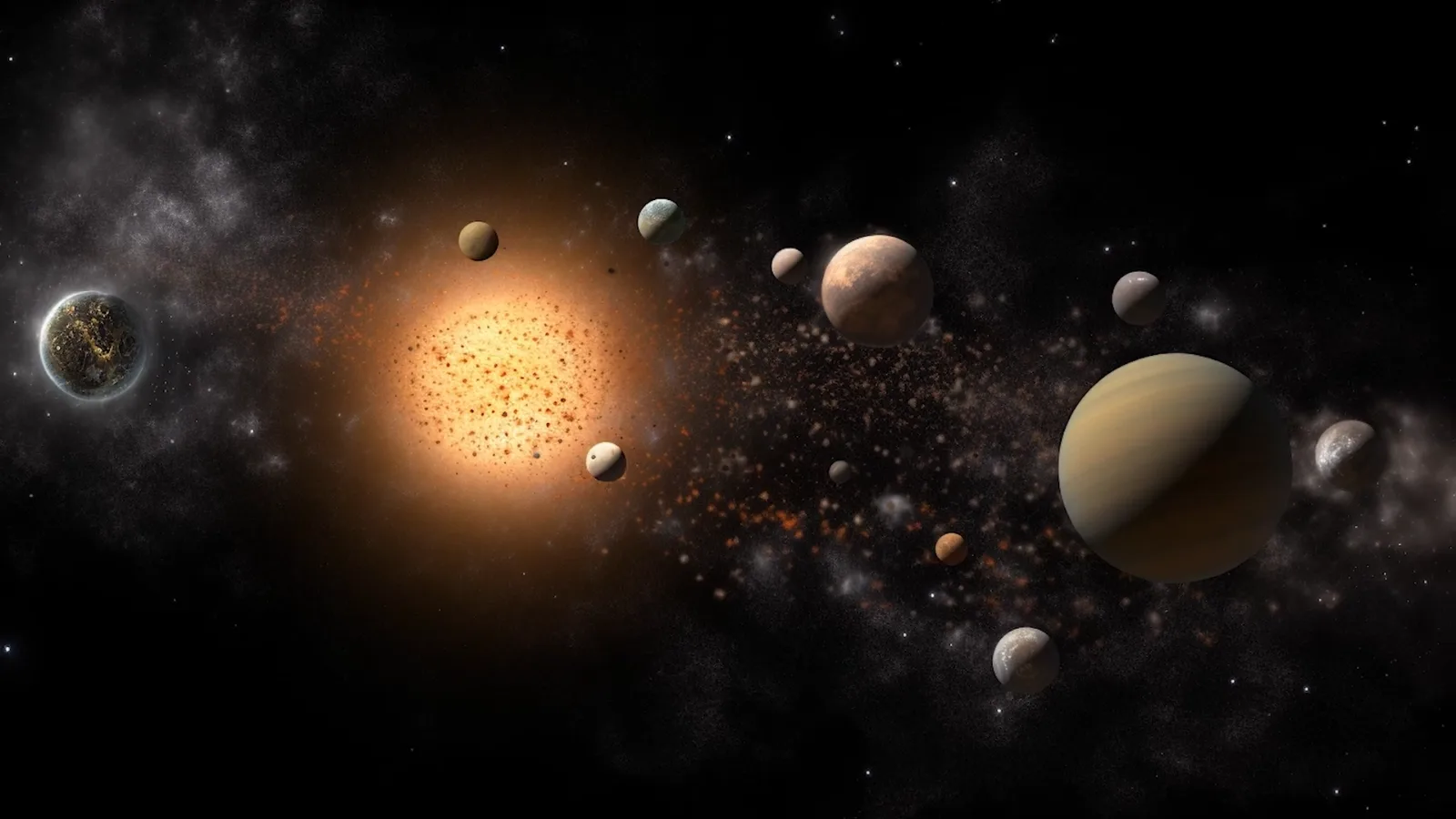

Astronomers at the University of California discovered that while a star can swallow small planets like Earth without much trouble, a super-Jupiter plunging into a star can unleash destructive shock waves so intense that the star’s entire atmosphere can be blasted away.

In extreme cases, it can even tear open parts of the star’s interior.

These collisions scatter debris into space—wreckage that can eventually merge into entirely new worlds.

This revelation raises a stunning possibility: some planets aren’t born in peaceful disks around young stars.

Some are forged from cataclysms—worlds built from the corpses of destroyed planets.

But what happens to the worlds that escape?

Billions of planets drift through the Milky Way completely alone.

These rogue planets were once part of traditional star systems, but gravitational chaos—collisions, close passes by another star, or the influence of a black hole—threw them into the abyss.

Once ejected, their surface temperatures plummet to –270°C (–455°F).

No sunlight.

No seasons.

No day or night.

Yet astrophysicist Manasvi Lingam believes some of these dark wanderers might still harbor life.

It sounds impossible—until you look at Earth.

Beneath Antarctica’s ice sheets, scientists have found liquid rivers and lakes heated solely by geothermal energy.

Deep under the frozen crust, entire ecosystems exist in complete darkness.

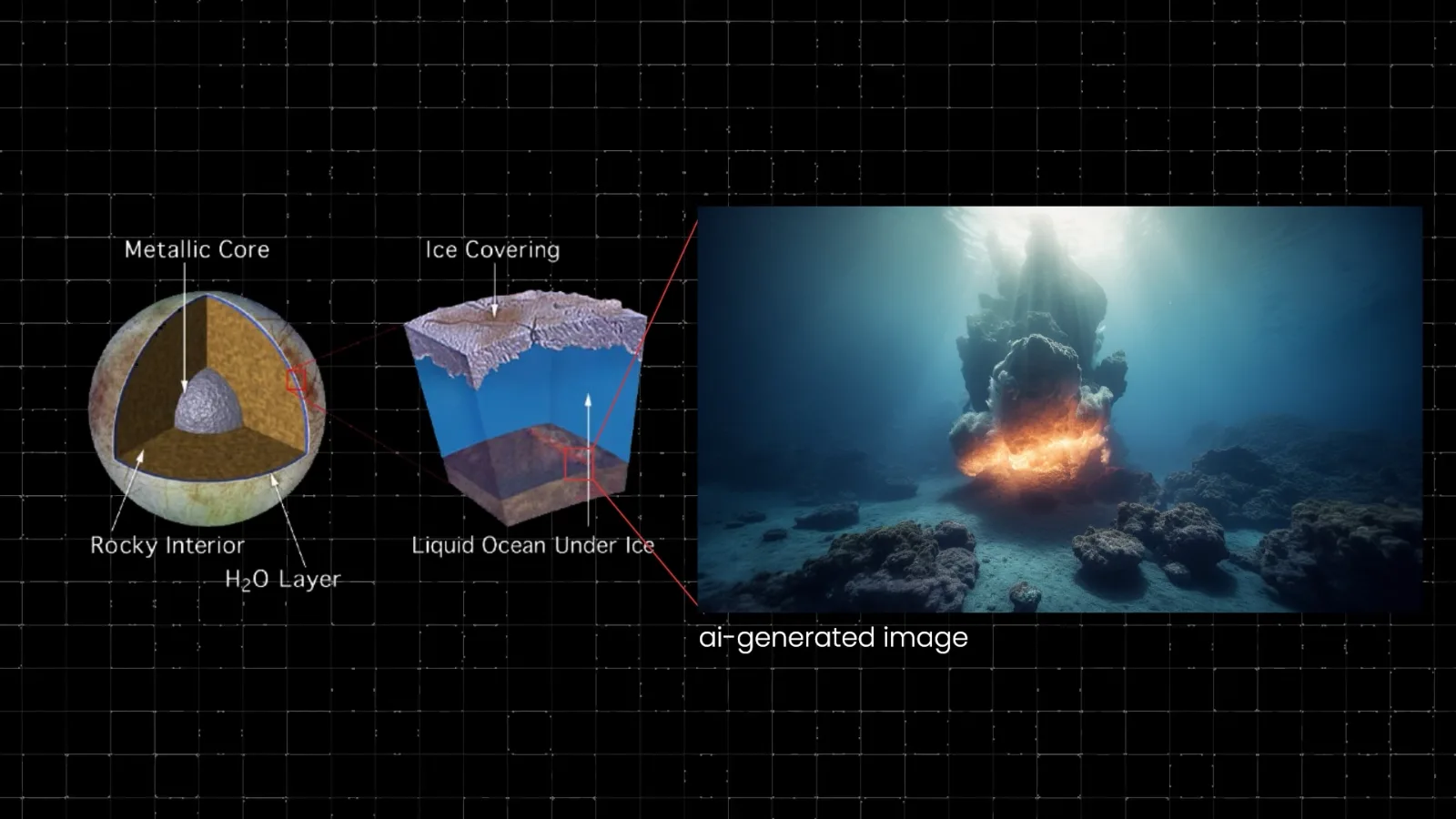

A rogue Earth-like planet could function the same way.

As long as it retains an atmosphere, internal heat from radioactive decay could sustain liquid oceans for billions of years.

Some wanderers might even have surface life if wrapped in a dense hydrogen atmosphere—a thermal blanket strong enough to trap interior heat.

And there’s more:

If such a rogue planet has a large moon, tidal forces would knead its interior, boosting heat production.

The same process warms Jupiter’s moon Io so intensely that it erupts with ceaseless volcanic activity.

For now, rogue planets remain hypothetical—but NASA is preparing to change that.

NASA is developing Extrasolar Object Interceptors, fast nuclear-powered probes equipped with electric propulsion.

Their job? Chase down interstellar bodies—including rogue planets—take samples, and return them to Earth.

If a wandering world ever drifts into our solar system, these interceptors could reach it and return samples in under a decade.

For the first time in history, we may soon touch material from a planet born in another star system.

But rogue planets are just one type of cosmic oddity.

Some worlds shouldn’t exist at all.

Located 2,300 light-years away in Virgo, PSR B1257+12 b, nicknamed Poltergeist, orbits a pulsar—an ultra-dense stellar remnant formed from a catastrophic supernova.

Planets shouldn’t survive such an explosion.

Yet Poltergeist did.

Astronomers now believe it formed from the debris after the supernova—a planet reborn from destruction.

Its rocky surface is constantly blasted by high-energy radiation, but a dense atmosphere could make the world habitable for radiation-resistant microbes.

Earth already hosts such organisms.

The bacterium Deinococcus radiodurans can survive 500 times the radiation a human can.

If life can thrive in nuclear reactors on Earth, perhaps it can endure Poltergeist’s inferno.

Just 63 light-years away, hidden behind a swirling disk of dust, astronomers discovered Beta Pictoris b—a super-Jupiter with a radius 1.

65 times larger than Jupiter and a mass 11 times greater.

Even stranger? It completes a rotation in just 8.1 hours, making it one of the fastest-spinning giants known.

But the biggest mystery:

Although it orbits 10 AU from its star (as far as Saturn is from the Sun), its temperature is an unbelievable 1,451°C.

There’s no accepted explanation.

Some theories suggest that residual heat from formation, combined with a massive dusty envelope, might trap heat—but no model fully explains the extreme temperature.

Discovered in 2022, this monster planet—nine times Jupiter’s mass—forms in a way never seen before.

It sits 100 times farther from its star than Earth is from the Sun, yet continues to accumulate material.

Traditional models say this should be impossible.

There simply isn’t enough gas or dust so far out in a system.

AB Aurigae b may have formed through gravitational fragmentation, where a young star’s disk collapses into planet-sized clumps.

If true, it challenges every modern theory of planet formation.

Orbiting a tiny red dwarf only 30 light-years away, GJ 3512 b is a gas giant half the size of Jupiter—despite orbiting a star that barely has enough mass to form planets at all.

It contradicts the long-held belief that small stars can only host small rocky planets.

This discovery forces astronomers to revisit everything they thought they understood about planetary formation.

From planet-eating stars to frozen ocean worlds, from supernova survivors to impossible giants, these strange planets reveal a universe far stranger—and more violent—than we ever imagined.

In the coming decade, missions like the James Webb Space Telescope and ESA’s Ariel (launching 2029) will uncover even more bizarre worlds.

One thing is certain:

Every time we think we know how planets should form or behave, the cosmos proves us wrong.

News

“Screaming Silence: How I Went from Invisible to Unbreakable in the Face of Family Betrayal”

“You’re absolutely right. I’ll give you all the space you need.” It’s a mother’s worst nightmare—the slow erosion of her…

“From Invisible to Unstoppable: How I Reclaimed My Life After 63 Years of Serving Everyone Else”

“I thought I needed their approval, their validation. But the truth is, I only needed myself.” What happens when a…

“When My Son Denied Me His Blood, I Revealed the Secret That Changed Everything: A Journey from Shame to Triumph”

“I thought I needed my son’s blood to save my life. It turned out I’d saved myself years ago, one…

“When My Daughter-in-Law Celebrated My Illness, I Became the Most Powerful Woman in the Room: A Journey of Betrayal, Resilience, and Reclaiming My Life”

“You taught me that dignity isn’t about what people give you, it’s about what you refuse to lose. “ What…

“When My Sister-in-Law’s Christmas Gala Turned into My Liberation: How I Exposed Their Lies and Found My Freedom”

“Merry Christmas, Victoria. ” The moment everything changed was when I decided to stop being invisible. What happens when a…

On My Son’s Wedding Day, I Took Back My Dignity: How I Turned Betrayal into a Legacy

“You were always somebody, sweetheart. You just forgot for a little while.” It was supposed to be the happiest day…

End of content

No more pages to load