In the quiet darkness past Jupiter, a cosmic oddball has been acting like a firecracker for nearly a century.

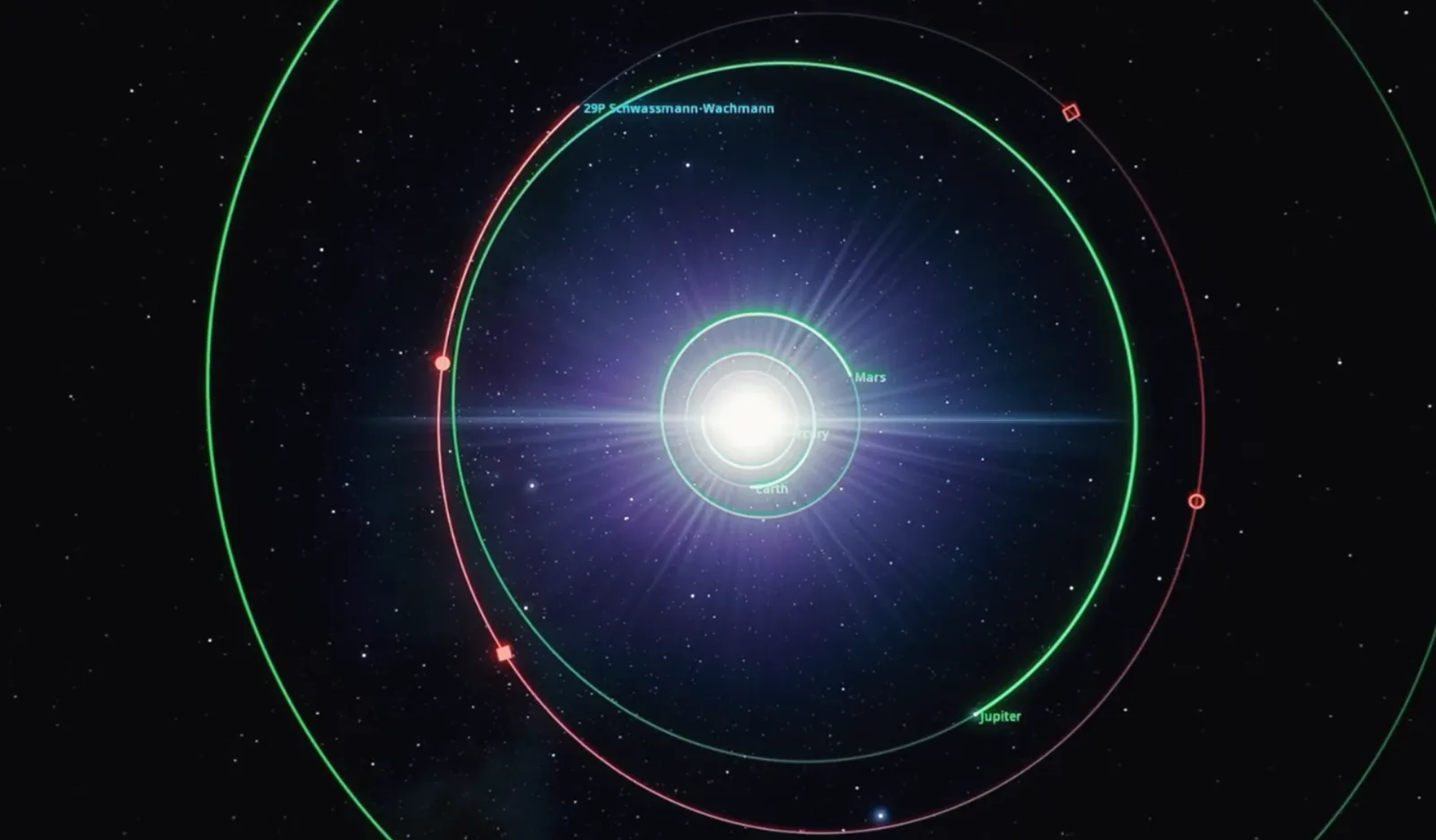

Known today as Centaur 29P/Schwassmann–Wachmann, this icy world sits in an unexpectedly calm region of the solar system — yet erupts with violent outbursts dozens of times each year.

Astronomers describe it as “the most explosive comet we’ve ever observed,” and its behavior is so extreme that scientists still cannot agree on what drives its fury.

First discovered in 1927 by astronomers Arnold Schwassmann and Arno Arthur Wachmann, 29P was initially thought to be a normal periodic comet.

But as more observations accumulated, its identity shifted.

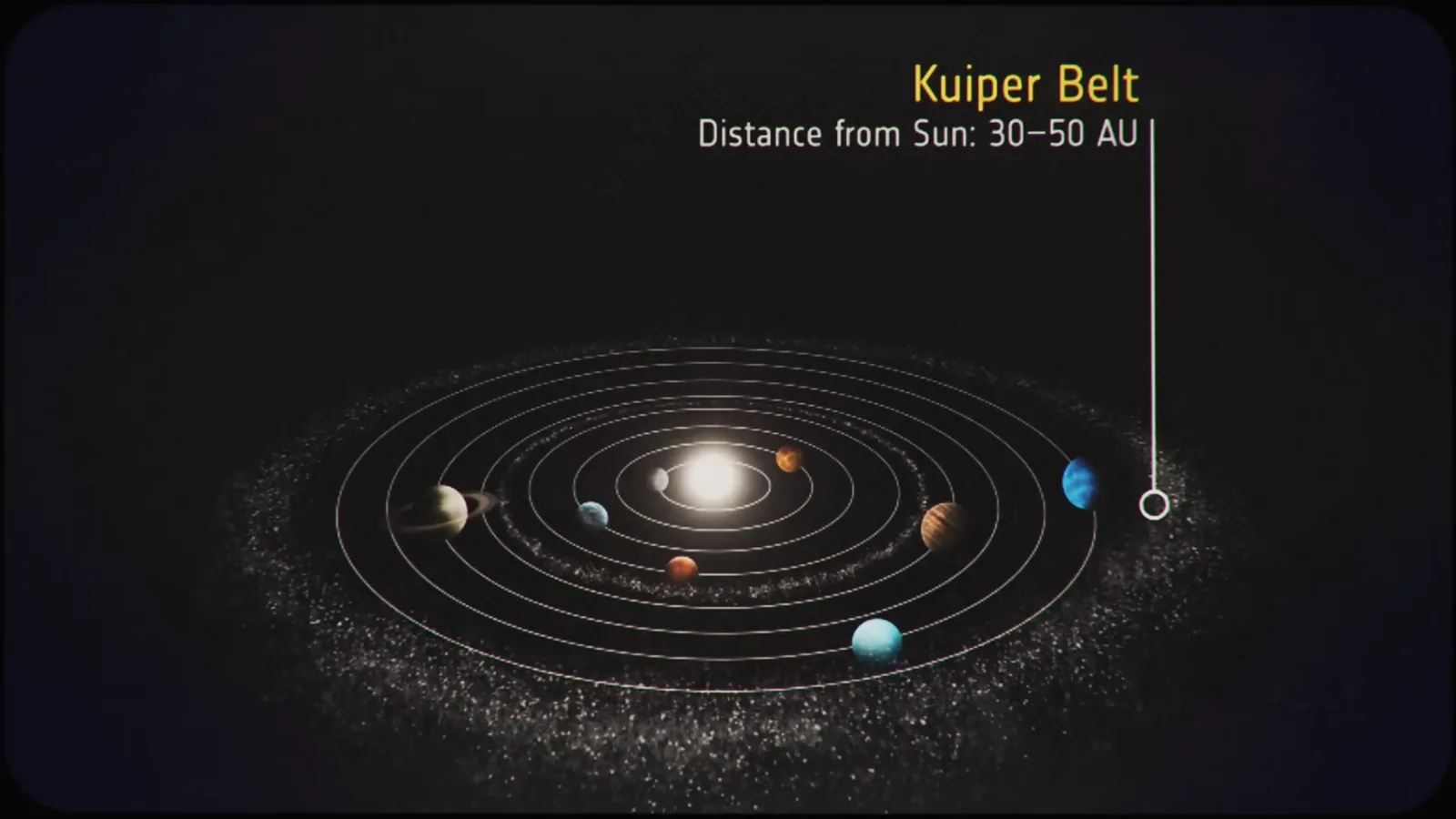

It was reclassified as a Centaur, a hybrid population that orbits between Jupiter and Neptune — part asteroid, part comet — and represents a transitional stage for objects migrating inward from the Kuiper Belt.

Most Centaurs follow unstable, elliptical orbits heavily influenced by gravitational nudges from the giant planets.

They eventually become Jupiter-family comets or are ejected from the solar system.

But 29P breaks the trend in two unusual ways:

its orbit is nearly a perfect circle, and

its size is enormous — about 60 kilometers across, making it larger than the overwhelming majority of known Centaurs.

And unlike almost any other object in its category… 29P explodes.

Not once in a while.

Not seasonally.

But relentlessly.

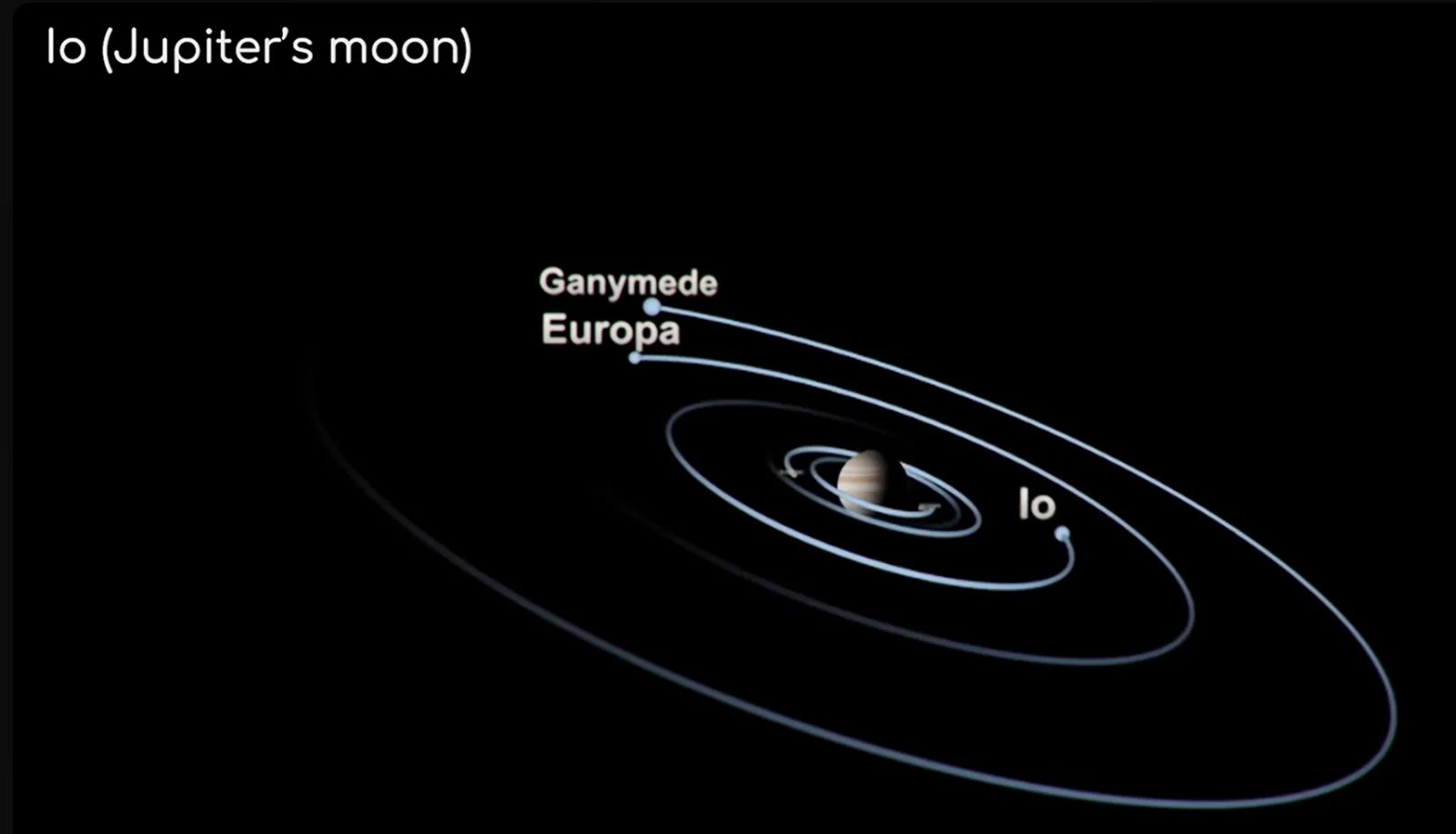

It erupts roughly 30 times a year, making it the second most active body in the entire solar system after Jupiter’s volcanic moon Io.

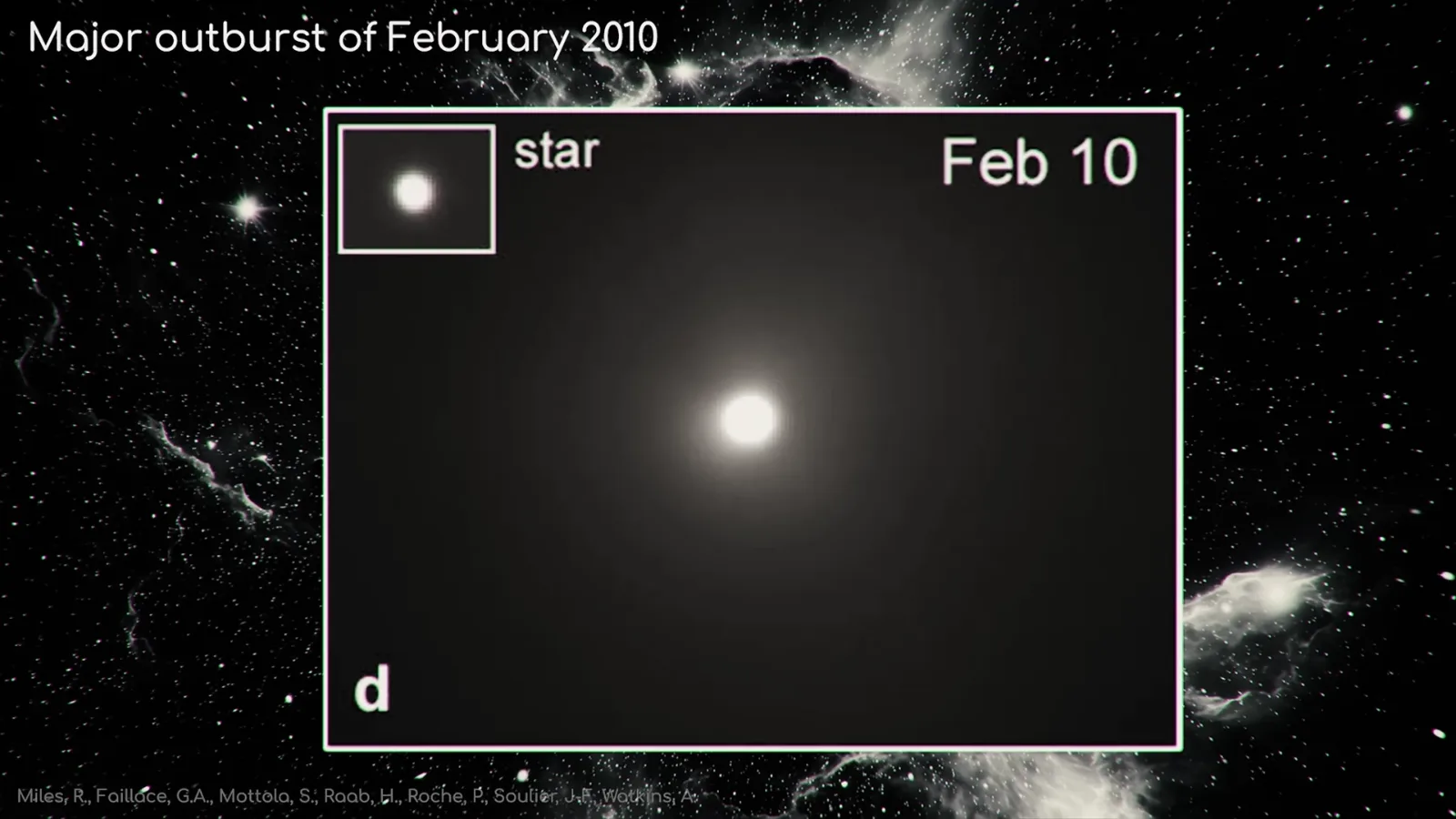

Its blasts can make it jump almost 300 times brighter within hours.

In 2024, it erupted four times within 48 hours, spewing more than a million tons of debris faster than the speed of sound — a phenomenon more reminiscent of a ruptured pressure tank than a sleepy outer-system comet.

The eruptions are so unpredictable that most are detected first not by professional observatories but by dedicated amateur astronomers.

In one legendary 2021 event — the largest outburst in four decades — 29P erupted five times in succession, yet professional telescopes failed to capture the first blasts.

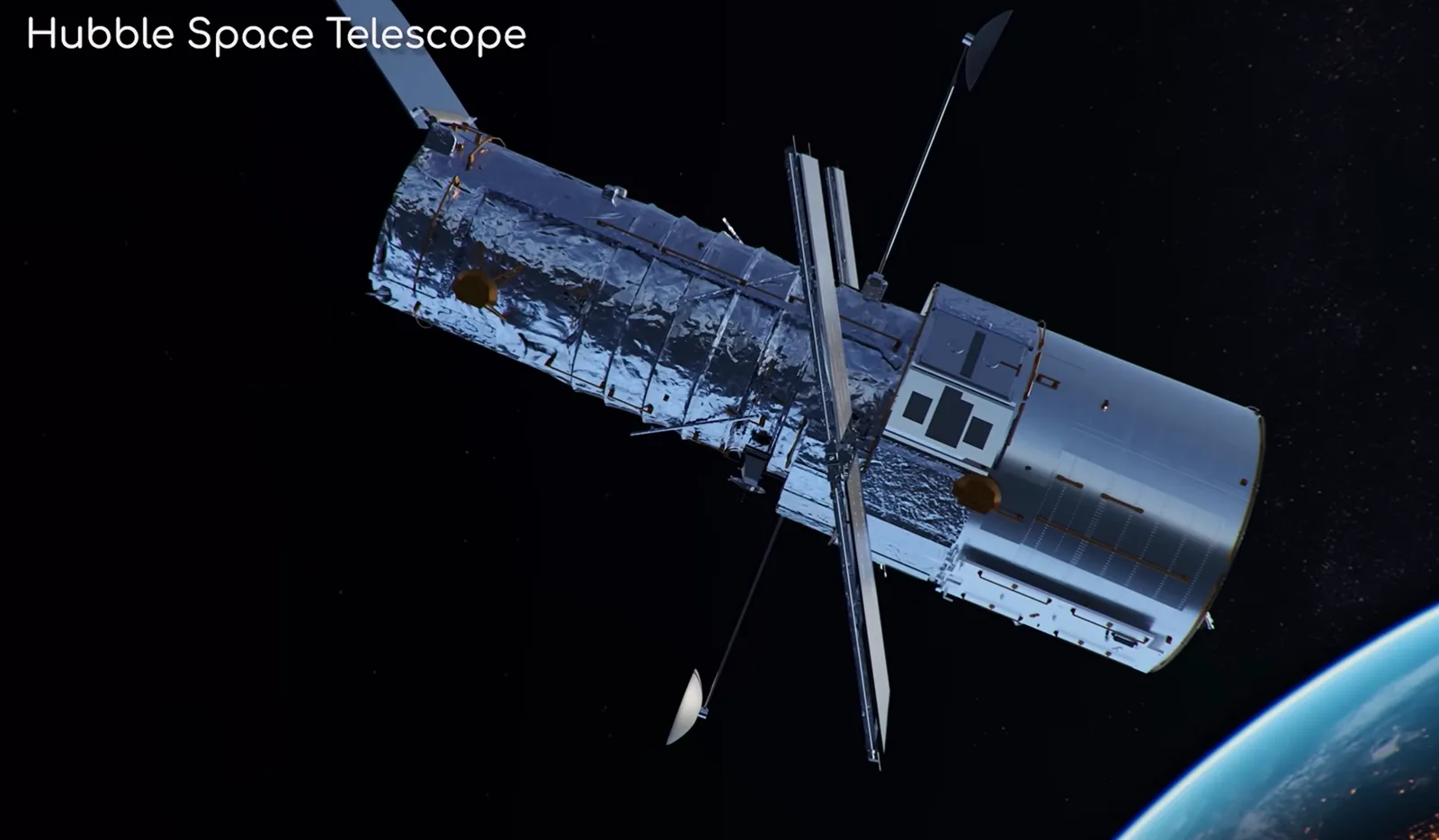

When scientists scrambled to schedule Hubble observations, the telescope suffered a technical malfunction, almost as if the universe wanted to keep 29P’s secrets buried a little longer.

To understand this chaotic behavior, researchers turned their focus to the comet’s internal structure.

Centaur 29P is believed to be cryovolcanic — its eruptions powered not by molten rock but by volatile chemicals such as carbon monoxide, nitrogen, and carbon dioxide.

Solar radiation weakens its icy crust over time, sublimating frozen gases and building enormous pressure beneath the surface.

When the crust can no longer contain it, 29P blows out, sometimes violently enough to trigger secondary eruptions days later.

The result is a haze of dust and ice around the comet, making it appear dramatically brighter for days or weeks.

Other cryovolcanic comets, such as the famous “Devil Comet” 12P/Pons-Brooks, erupt when their eccentric orbits bring them closer to the Sun.

But this explanation fails for 29P: its orbit is circular.

It receives nearly constant sunlight, so its activity should be steady — yet its eruptions are anything but.

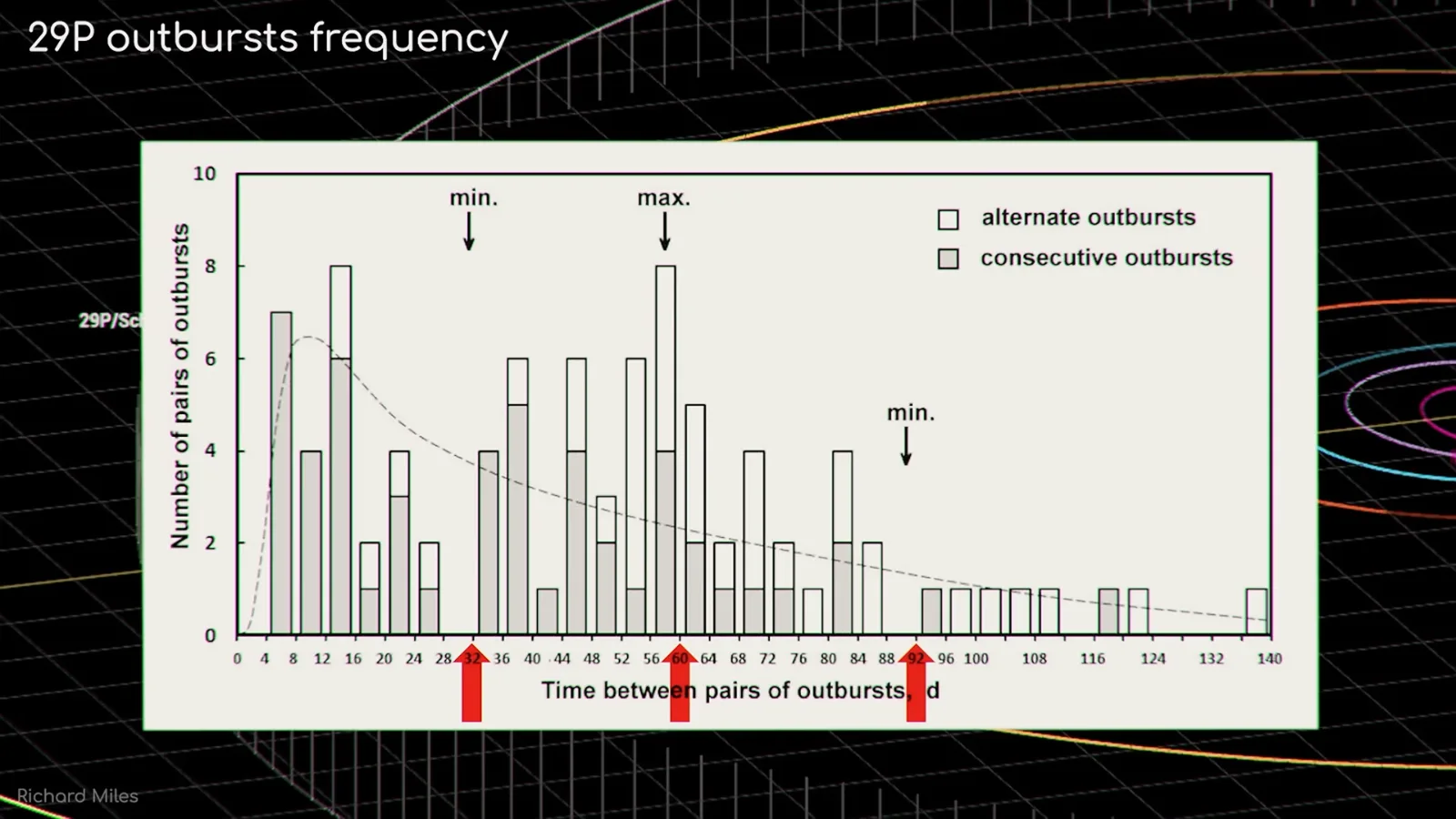

Scientists began looking for patterns.

Some suspected the comet’s 57-day rotation period may play a role, as major outbursts seemed to cluster around 52 to 60 days apart.

Others noticed weaker cycles every 30 and 90 days, hinting at complex seasonal effects on the comet’s surface.

But although these rhythms exist, they fail to predict the timing or strength of the biggest blasts.

That changed briefly in April 2023, when astronomers noticed the coma around 29P dimming more than usual.

They predicted pressure was building rapidly inside the nucleus — and hours later, the comet erupted exactly as anticipated.

It was the first time anyone had successfully predicted an outburst from this volatile object.

But the greatest breakthroughs came when scientists turned the James Webb Space Telescope toward 29P.

Before 2024, we had never detected carbon dioxide on the comet directly — only carbon monoxide.

Radio observations had long shown a jet of CO gas aimed toward Earth, suggesting CO was driving the eruptions.

But when Webb’s Near-Infrared Spectrograph examined the comet, the picture radically changed.

Webb revealed not one but two distinct carbon monoxide jets, as well as two jets of carbon dioxide — the first confirmed detection of CO₂ on the comet.

Even more intriguing was what the differing compositions suggested: that 29P might not be a single object at all, but a cluster of smaller bodies fused together over time.

This idea helps explain the chaotic outgassing but still leaves a deeper puzzle unsolved: where does 29P get so much carbon monoxide?

CO is incredibly volatile.

If pure CO ice existed near the surface, it would have escaped millions of years ago.

Its presence today implies the gas is somehow trapped deep below the surface.

The leading theory points to amorphous water ice, a porous form of ice common in the frigid Kuiper Belt.

Amorphous ice can trap large amounts of gas within its structure.

When exposed to warmer temperatures — above 77 Kelvin — it gradually converts into crystalline ice, releasing the gas in sudden bursts.

Because 29P is so much larger than typical Centaurs, its deep interior may still contain significant amounts of amorphous ice.

Models suggest smaller Centaurs convert their amorphous ice within a few million years, but a massive object like 29P could take up to 100 million years.

That means the comet may still be halfway through a slow, destructive transformation, with gas release and structural collapses driving its chaotic eruptions.

This theory explains much — but not everything.

29P still erupts too often, and often too violently, for slow crystallization alone.

Some researchers think internal caverns may collapse suddenly, causing chain-reaction sinkholes.

Others believe layers of ice and dust might act like pressure valves, rupturing sporadically as thermal stresses shift.

But no single explanation fully captures the unpredictability of its behavior.

The truth is, Centaur 29P remains one of the most mysterious objects in the solar system.

Its violent personality challenges our assumptions about what icy bodies can do, and every new observation deepens the mystery rather than solves it.

With more eyes — human and telescopic — turning its way, we may one day decode the physics behind its thunderous eruptions.

For now, though, 29P remains a frozen enigma — a cosmic bomb that refuses to stop going off.

News

“Screaming Silence: How I Went from Invisible to Unbreakable in the Face of Family Betrayal”

“You’re absolutely right. I’ll give you all the space you need.” It’s a mother’s worst nightmare—the slow erosion of her…

“From Invisible to Unstoppable: How I Reclaimed My Life After 63 Years of Serving Everyone Else”

“I thought I needed their approval, their validation. But the truth is, I only needed myself.” What happens when a…

“When My Son Denied Me His Blood, I Revealed the Secret That Changed Everything: A Journey from Shame to Triumph”

“I thought I needed my son’s blood to save my life. It turned out I’d saved myself years ago, one…

“When My Daughter-in-Law Celebrated My Illness, I Became the Most Powerful Woman in the Room: A Journey of Betrayal, Resilience, and Reclaiming My Life”

“You taught me that dignity isn’t about what people give you, it’s about what you refuse to lose. “ What…

“When My Sister-in-Law’s Christmas Gala Turned into My Liberation: How I Exposed Their Lies and Found My Freedom”

“Merry Christmas, Victoria. ” The moment everything changed was when I decided to stop being invisible. What happens when a…

On My Son’s Wedding Day, I Took Back My Dignity: How I Turned Betrayal into a Legacy

“You were always somebody, sweetheart. You just forgot for a little while.” It was supposed to be the happiest day…

End of content

No more pages to load