“If you could see Geminga with your eyes, its invisible glow would dominate the sky—along with the antimatter it’s quietly hurling at us.”

We tend to think of space as distant and detached from our daily lives.

Stars twinkle overhead, galaxies drift silently beyond our reach, and the night sky feels more like a backdrop than a battlefield.

But high above our atmosphere, something extraordinary is happening.

Tiny bullets of antimatter—positrons—are constantly streaming in from the depths of space and slamming into Earth.

For years, scientists had no idea where this strange surplus of positrons was coming from.

Dark matter was a prime suspect.

But new observations have revealed a different culprit: an 800-light-year-away cosmic engine known as **Geminga**, a pulsar with a story as wild as the particles it sends our way.

Up in the constellation Gemini, buried in what looks like empty sky, lies one of the most intriguing objects in the Milky Way.

Back in 1972, NASA’s **Small Astronomy Satellite 2 (SAS-2)** detected a mysterious source of high-energy gamma rays in that region.

The signal was there—but the source itself remained hidden.

No visible star, no nebula.

Just a hazy patch of gamma radiation with no obvious origin.

Italian physicist **Giovanni Bignami** became obsessed with it.

In 1976, he christened the source **Geminga**—a clever mashup of GEMini and GAMma, and also a pun in the Milanese dialect meaning “it’s not there.

” The name fit perfectly: a powerful gamma-ray glow that seemed to come from… nothing.

The breakthrough came in 1983, when the **Einstein X-ray satellite** picked up a faint X-ray source in the same region.

It narrowed the search, but still didn’t reveal exactly what Geminga was.

Then, in the early 1990s, the puzzle pieces fell into place.

Two missions—Germany’s **ROSAT** X-ray telescope and NASA’s **EGRET** gamma-ray telescope—detected *pulses* of radiation.

Not continuous waves, but rhythmic flashes, repeating every 0.237 seconds.

Roughly four times a second, Geminga blinked.

That regular cosmic heartbeat gave the game away:

Geminga was a **pulsar**.

A pulsar is the collapsed core of a massive star, a **neutron star** only about 20–30 km across but containing more mass than our Sun.

It spins rapidly and emits beams of radiation from its magnetic poles, sweeping the cosmos like the beams from a lighthouse.

If one of those beams crosses Earth, we detect regular pulses.

Most pulsars are found in **radio wavelengths**, emitting strong radio pulses that make them relatively easy to spot with radio telescopes.

But Geminga was different.

Unlike famous pulsars like **Crab** and **Vela**, Geminga seemed *radio silent*.

It glowed brilliantly in gamma rays—around 99% of its energy emerges at those extreme wavelengths—but produced no radio signal we could detect.

It also lacked the bright, obvious nebula surrounding Crab and Vela.

A pulsar with no radio signal and no visible nebula? Astronomers were baffled.

For decades, Geminga became the poster child for strange pulsars—loud in gamma rays, silent in radio, and still cloaked in mystery.

The first clue to its radio behavior came in 1997.

Using a highly sensitive antenna at the Pushchino Radio Astronomy Observatory, three independent teams detected **extremely faint radio pulses** from Geminga.

The catch? These pulses appeared at about **100 MHz**, a low radio frequency most telescopes hadn’t been listening at.

We had assumed Geminga was radio silent.

In reality, we were simply listening in the wrong place.

Further work suggested that **Geminga’s magnetic field** might absorb or distort most radio waves inside its magnetosphere, allowing only the lowest frequencies to leak out as weak, ghostlike pulses.

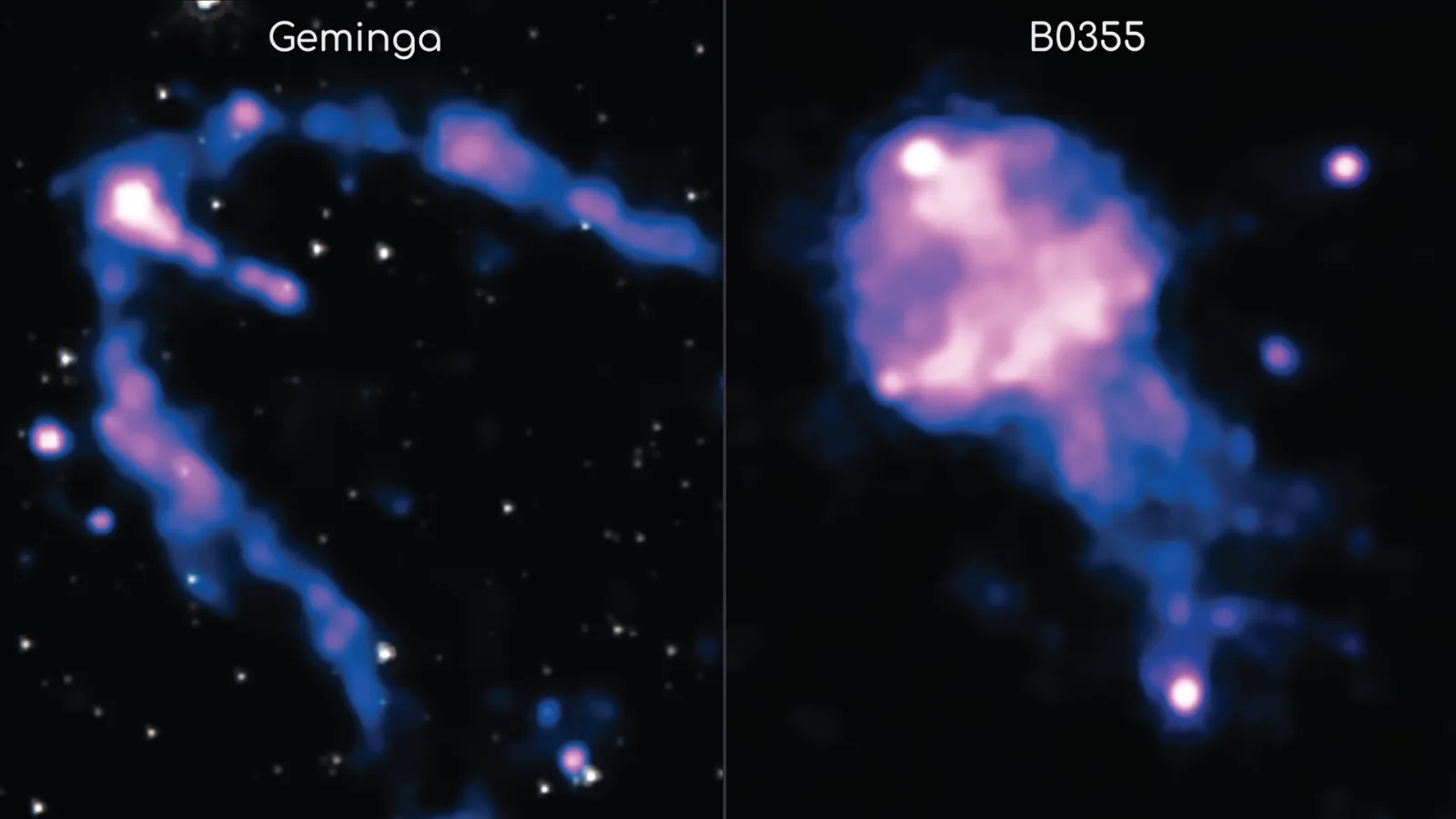

Its nebula mystery was solved later, too.

In the early 2000s, observations from **XMM-Newton** and later confirmation from other instruments revealed two spectacular, comet-like **X-ray tails** streaming behind Geminga, stretching **trillions of kilometers**.

These are powered by the pulsar barreling through the interstellar medium at around **210 km/s**—a stellar bullet crossing space.

By 2005, astronomers identified a **pulsar-wind nebula** around Geminga: a faint shell of neutral hydrogen and high-energy plasma driven by a relentless wind of electrons and positrons pouring out of the pulsar.

The missing nebula was there all along—it just took the right instruments to see it.

Geminga’s properties are extreme even by pulsar standards:

Distance: ~**800 light-years**

Radius: ~**20–30 km**

Mass: about **1.5 times the Sun’s

Density: a teaspoon of its material would weigh billions of tons

As it spins and races through space, Geminga’s intense magnetic field rips particles off its surface and accelerates them to near light speed.

These include both **electrons** and their antimatter siblings, **positrons**.

Some of these particles spiral along magnetic field lines, producing intense gamma-ray beams we detect as Geminga’s pulses.

Others escape into space, forming a vast halo of high-energy particles that drift far beyond the pulsar’s immediate neighborhood.

For a long time, this was just an interesting bit of astrophysics.

Then something above our heads began counting positrons—by the hundreds of thousands.

In 2011, NASA’s **Alpha Magnetic Spectrometer (AMS-02)**, attached to the **International Space Station**, began capturing high-energy charged particles from space.

By 2013, scientists analyzing its data made a startling announcement:

There were far more high-energy positrons hitting Earth than expected.

We’d always known that cosmic rays and natural processes could produce some positrons.

But AMS-02 showed a **huge excess**—hundreds of thousands of them.

The obvious question was: *Where were they coming from?*

For years, one exciting possibility took center stage: Dark matter.

If dark matter particles annihilated each other, they might produce excess positrons as a by-product.

This made the AMS-02 positron anomaly a tantalizing potential clue in one of modern physics’ greatest mysteries.

But as more data poured in, the case for dark matter became weaker.

The energy spectrum and distribution of the positrons pointed toward a more mundane but still extraordinary source: **pulsars**.

And right in our cosmic backyard, Geminga was a prime suspect.

In 2017, the **HAWC Gamma-Ray Observatory** detected a compact gamma-ray halo around Geminga, in the multi-TeV range (5–40 trillion electron volts).

The halo’s properties suggested that electrons and positrons from Geminga were colliding with starlight and upscattering it to gamma-ray energies.

But the halo HAWC saw was relatively small.

That led some to argue that particles from Geminga couldn’t reach Earth efficiently, and that the positron excess must be from something else.

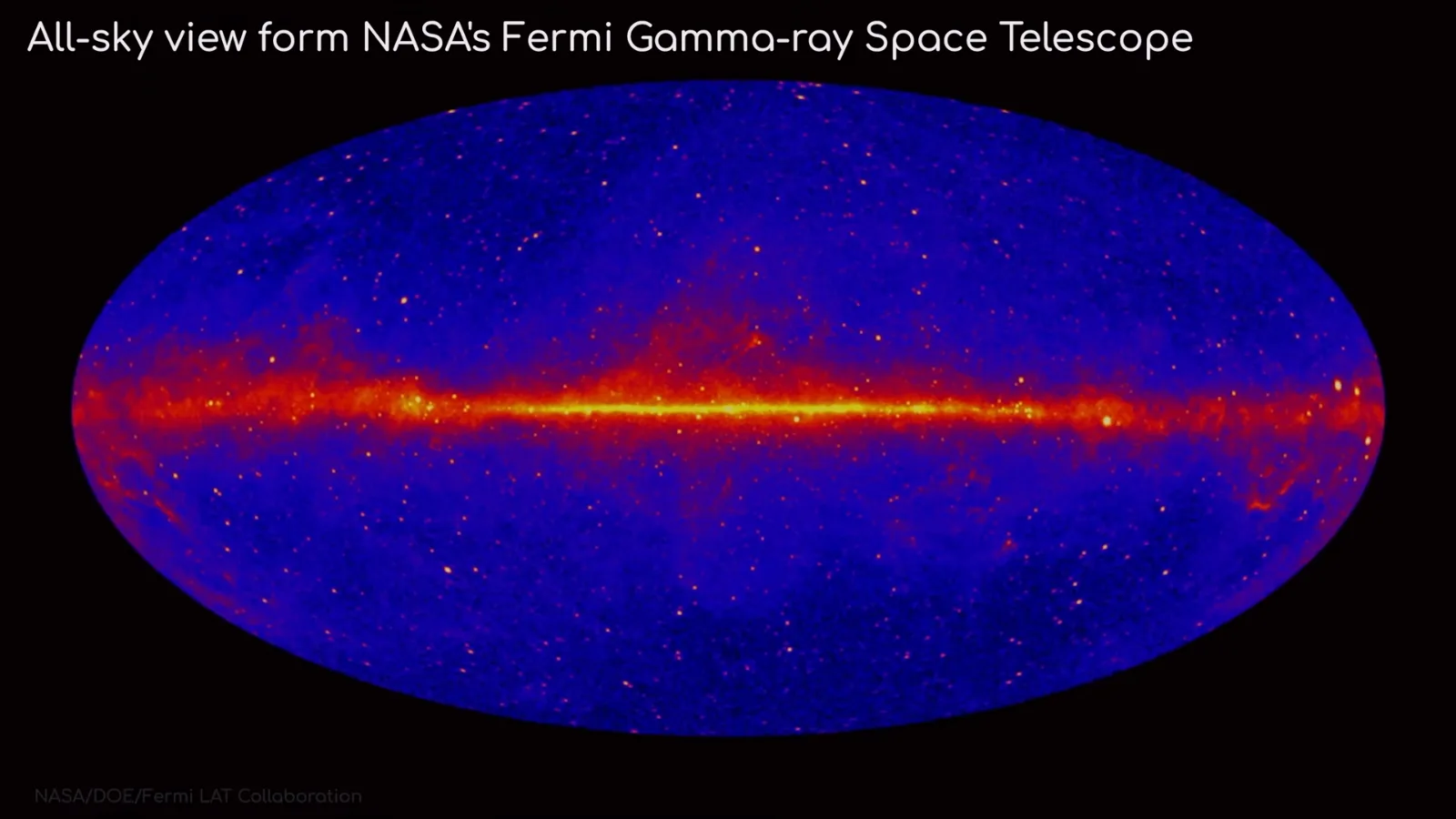

Then, astrophysicist **Mattia Di Mauro** and his team took a decade of data from **Fermi’s Large Area Telescope** and did something more drastic: they subtracted out every other known gamma-ray source.

What remained was stunning.

A huge, oblong gamma-ray halo** surrounding Geminga at ~10 billion electron volts, spanning about 20 degrees of sky—roughly the size of the Big Dipper.

At even lower energies, the halo would be even larger.

If your eyes could see gamma rays, Geminga’s glow would dominate a massive patch of our sky, covering an area **40 times larger than the full Moon**.

From the size and energy distribution of this halo, Di Mauro’s team calculated that **Geminga alone could account for up to 20% of the excess positrons detected near Earth

If just one pulsar can do that, it doesn’t take many more to explain the rest.

The likely conclusion?

Pulsars—not dark matter—are the main suppliers of the antimatter shower hitting our planet.

That may sound like a letdown for dark matter hunters, but it’s actually a huge scientific win.

In less than a century, pulsars have gone from being mistaken for alien beacons (“LGM” for Little Green Men, in Jocelyn Bell Burnell’s notebook) to becoming laboratories of extreme physics—testing grounds for relativity, nuclear matter, magnetism, and high-energy particles.

Geminga, first discovered as a nameless gamma-ray smudge in the 1970s, has now:

* Helped confirm the existence of **radio-quiet gamma-ray pulsars**

* Revealed how pulsar orientation affects what we see from Earth

* Shown us how pulsar winds carve out **enormous nebulae and particle halos**

* Demonstrated that nearby pulsars can dramatically shape our **local cosmic ray environment**

And yet, it may still be hiding secrets: about magnetic fields, particle acceleration, and the structure of the interstellar medium.

We once thought the cosmos was distant and disconnected from our lives.

But above our heads, a stellar corpse the size of a city, spinning four times a second hundreds of light-years away, is quietly flooding our neighborhood with antimatter.

Not to destroy us.

But to teach us.

To show us that even in the emptiest space, invisible forces are at work, shaping what we detect, what we believe, and what we still have left to understand.

News

“Screaming Silence: How I Went from Invisible to Unbreakable in the Face of Family Betrayal”

“You’re absolutely right. I’ll give you all the space you need.” It’s a mother’s worst nightmare—the slow erosion of her…

“From Invisible to Unstoppable: How I Reclaimed My Life After 63 Years of Serving Everyone Else”

“I thought I needed their approval, their validation. But the truth is, I only needed myself.” What happens when a…

“When My Son Denied Me His Blood, I Revealed the Secret That Changed Everything: A Journey from Shame to Triumph”

“I thought I needed my son’s blood to save my life. It turned out I’d saved myself years ago, one…

“When My Daughter-in-Law Celebrated My Illness, I Became the Most Powerful Woman in the Room: A Journey of Betrayal, Resilience, and Reclaiming My Life”

“You taught me that dignity isn’t about what people give you, it’s about what you refuse to lose. “ What…

“When My Sister-in-Law’s Christmas Gala Turned into My Liberation: How I Exposed Their Lies and Found My Freedom”

“Merry Christmas, Victoria. ” The moment everything changed was when I decided to stop being invisible. What happens when a…

On My Son’s Wedding Day, I Took Back My Dignity: How I Turned Betrayal into a Legacy

“You were always somebody, sweetheart. You just forgot for a little while.” It was supposed to be the happiest day…

End of content

No more pages to load