“If this molecule is really there… it changes everything.”

A single line from NASA’s briefing — and suddenly the entire scientific community is holding its breath.

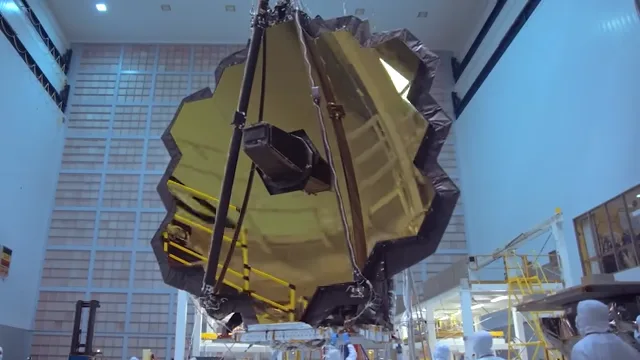

In less than two years, the James Webb Space Telescope has gone from humanity’s most ambitious experiment in space observation… to the most powerful scientific instrument ever pointed at the cosmos.

Its findings are rewriting astronomy at a breathtaking pace — and one discovery in particular has ignited the biggest debate in decades.

A potential sign of alien life.

But before we get to that, scientists needed to answer a fundamental question:

Is JWST actually powerful enough to detect life on a distant world?

To find out, researchers decided to run a bold experiment — by seeing whether Webb could detect life on the only inhabited planet we know: Earth.

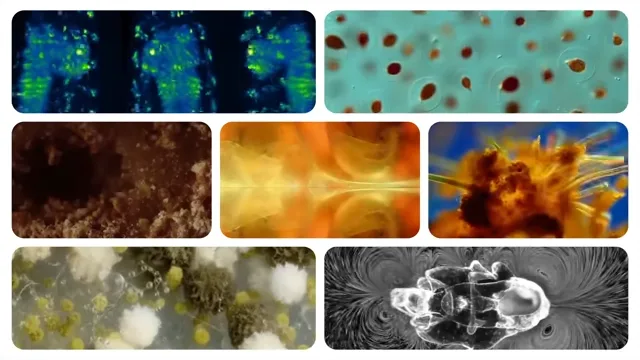

Scientists simulated what JWST would “see” if it observed Earth as an exoplanet orbiting a distant star.

They blurred and diluted Earth’s atmospheric data until it mimicked a signal coming from 40 light-years away — roughly the distance of the TRAPPIST-1 system.

They then used Webb’s own sensor profile to analyze the data.

The result shocked them.

Webb could detect oxygen, methane, and nitrogen dioxide — the exact biosignatures and technosignatures produced by Earth’s civilizations and biological life.

Not just that:

JWST could detect an alien civilization up to 50 light-years away.

But what happened next was even more extraordinary.

In 2023, Webb turned its gaze toward K2-18b, a planet roughly 120 light-years from Earth.

This world is unlike anything in our solar system — larger than Earth, smaller than Neptune, and covered in a deep global ocean beneath a hydrogen-rich atmosphere.

Scientists call it a Hycean world, and these planets may be more promising for life than Earth-like planets.

When Webb analyzed the starlight passing through K2-18b’s atmosphere, it detected:

Methane

Carbon dioxide

Low ammonia

Indicators of a water-rich environment.

But then came the molecule that set the world on fire:

Dimethyl sulfide (DMS).

On Earth, the only known natural source of DMS is life — primarily marine phytoplankton.

No volcanoes.

No lightning.

No abiotic geological process is known to produce it.

If DMS is confirmed, it would be the first biosignature ever found on an exoplanet.

Scientists are cautious, however.

K2-18b is far from Earth-like, and biosignatures can have deceptive origins — sometimes chemistry plays tricks we don’t yet understand.

But the possibility is now officially on the table:

There may be life 120 light-years away.

And JWST is just getting started.

While biosignature gases help, scientists are also studying how alien ecosystems might alter a planet’s appearance.

On early Earth, “purple bacteria” dominated the oceans.

Their pigments reflect light differently from plants, creating a distinct signature — similar to the “red edge” scientists look for today, but shifted into new wavelengths.

Simulations show that if a planet were covered in such bacteria, and had relatively clear skies, Webb could detect their spectral fingerprint.

Alien life might not be green.

It might not breathe oxygen.

It might glow purple from space.

JWST allows scientists to look for these signatures — a new frontier in exoplanet biology.

But the telescope is also changing our understanding of the early universe.

JWST has detected what appear to be galaxies that are far too massive, too bright, and too old to exist so soon after the Big Bang.

But some scientists now believe they may not be galaxies at all.

They might be “dark stars.”

These theoretical stars would be:

a million times more massive than the Sun

cold on the surface

but glowing incredibly bright

powered not by fusion, but dark matter annihilation

If true, this would be the first evidence that dark matter interacts with itself, releasing energy.

Dark stars could also solve three huge mysteries:

Why early galaxies appear too massive

Dark stars grow rapidly, looking like galaxies from far away.

Why supermassive black holes already existed 300 million years after the Big Bang

Collapsed dark stars could provide the seeds.

The nature of dark matter

Their existence would prove dark matter can self-annihilate, producing photons.

Suddenly, JWST isn’t just looking for life…

It may be revealing an entire missing chapter of cosmic evolution.

Through gravitational lensing, Webb detected two stars so luminous that even magnification from a galaxy cluster couldn’t explain them.

One is a binary system nicknamed Mothra, the other — Godzilla — is the brightest star ever observed.

But something doesn’t add up.

Their brightness suggests additional magnification from a massive, invisible object:

too massive to be a star

too small to be a galaxy

completely undetectable by Webb

The leading suspects?

A dark-matter–rich dwarf galaxy

or

an intermediate-mass black hole.

Either way, the universe is hiding far more than we realized.

The James Webb Space Telescope has already:

challenged our models of galaxy formation

possibly identified the first dark stars

spotted the brightest stars ever recorded

probed planets for life-bearing molecules

hinted at alien ocean worlds

And we’re only in the second year.

As more data arrives, one thing becomes clear:

The universe is not what we thought it was — it’s far more complex, more active, and more alive than we ever imagined.

News

“Screaming Silence: How I Went from Invisible to Unbreakable in the Face of Family Betrayal”

“You’re absolutely right. I’ll give you all the space you need.” It’s a mother’s worst nightmare—the slow erosion of her…

“From Invisible to Unstoppable: How I Reclaimed My Life After 63 Years of Serving Everyone Else”

“I thought I needed their approval, their validation. But the truth is, I only needed myself.” What happens when a…

“When My Son Denied Me His Blood, I Revealed the Secret That Changed Everything: A Journey from Shame to Triumph”

“I thought I needed my son’s blood to save my life. It turned out I’d saved myself years ago, one…

“When My Daughter-in-Law Celebrated My Illness, I Became the Most Powerful Woman in the Room: A Journey of Betrayal, Resilience, and Reclaiming My Life”

“You taught me that dignity isn’t about what people give you, it’s about what you refuse to lose. “ What…

“When My Sister-in-Law’s Christmas Gala Turned into My Liberation: How I Exposed Their Lies and Found My Freedom”

“Merry Christmas, Victoria. ” The moment everything changed was when I decided to stop being invisible. What happens when a…

On My Son’s Wedding Day, I Took Back My Dignity: How I Turned Betrayal into a Legacy

“You were always somebody, sweetheart. You just forgot for a little while.” It was supposed to be the happiest day…

End of content

No more pages to load