When the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) offered humanity its clearest window into the early universe, astronomers expected to find a calm, sparsely populated cosmos.

Instead, what they found was unsettling: the early universe was too busy, too bright, and far too mature.

Galaxies appeared billions of years “ahead of schedule,” shining with more light than their age should allow.

And at their centers lurked black holes far larger than they had any right to be only a few hundred million years after the Big Bang.

For months, astrophysicists whispered the phrase no one wanted to say out loud:

“Is cosmology broken?”

Some crises eased as better data came in.

Others deepened.

But one mystery — the impossible speed at which early black holes grew — refused to go away.

Then a new object entered the spotlight: a distant, dim red dot whose behavior was so extreme it now threatens to rewrite the rules of black-hole physics.

Its name is LID-568, and it appears to be breaking the Eddington Limit, a fundamental constraint that has shaped our understanding of cosmic growth for over a century.

The Early-Universe Crisis That Started It All

To understand why LID-568 matters, we must return to JWST’s first deep-field images.

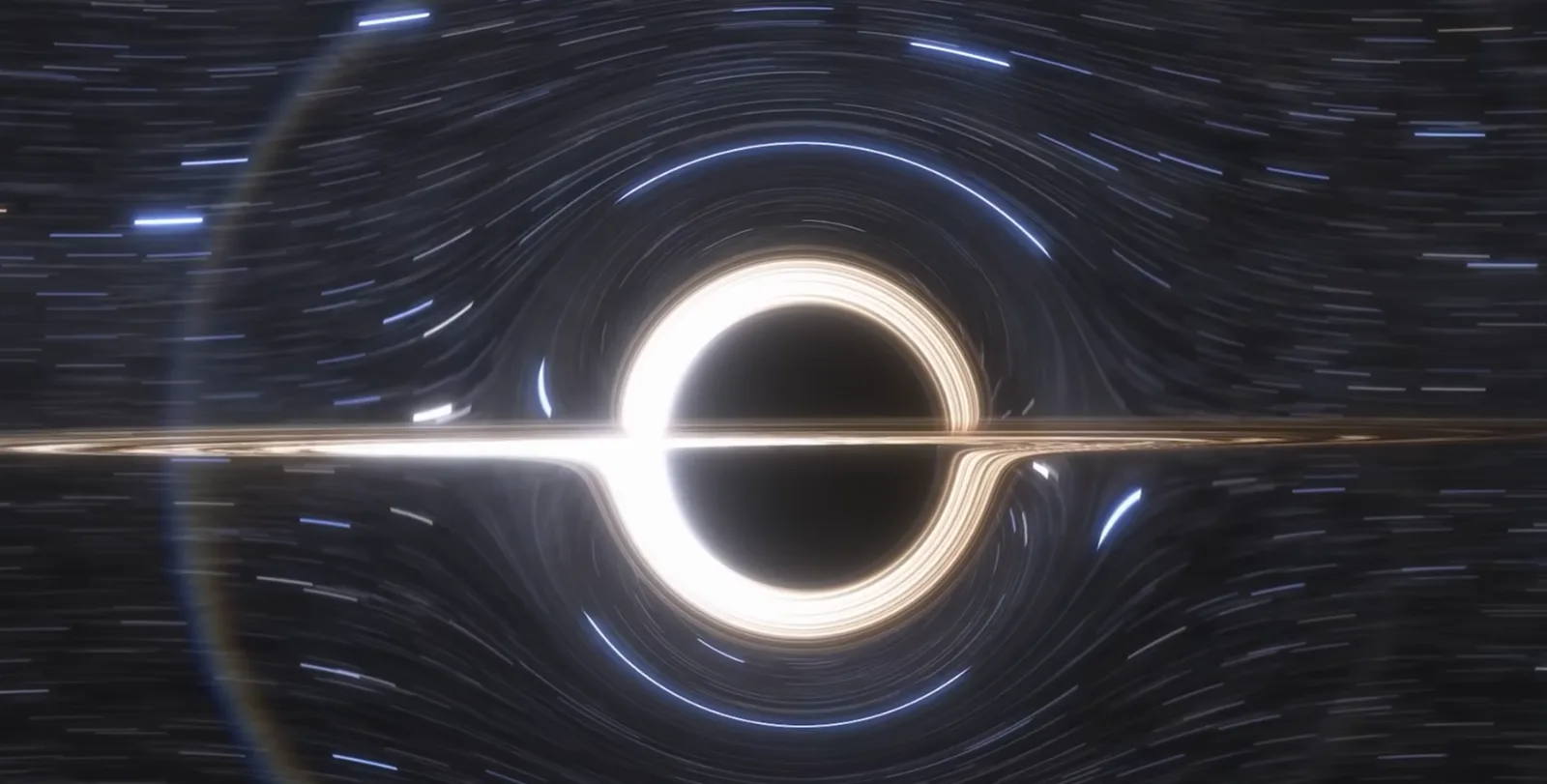

These pictures showed galaxies from 13 billion years ago, glowing with unexpected intensity.

At first, astronomers thought these galaxies were crammed with too many stars — far more than could have formed so early.

But researchers at UT Austin proposed a bold explanation:

the extra brightness wasn’t from stars at all — it was from enormous black holes feeding violently in their centers.

This revelation fixed one problem… and exposed another.

If these black holes were already supermassive, how did they form so quickly? Stellar black holes — created from collapsed stars — grow slowly.

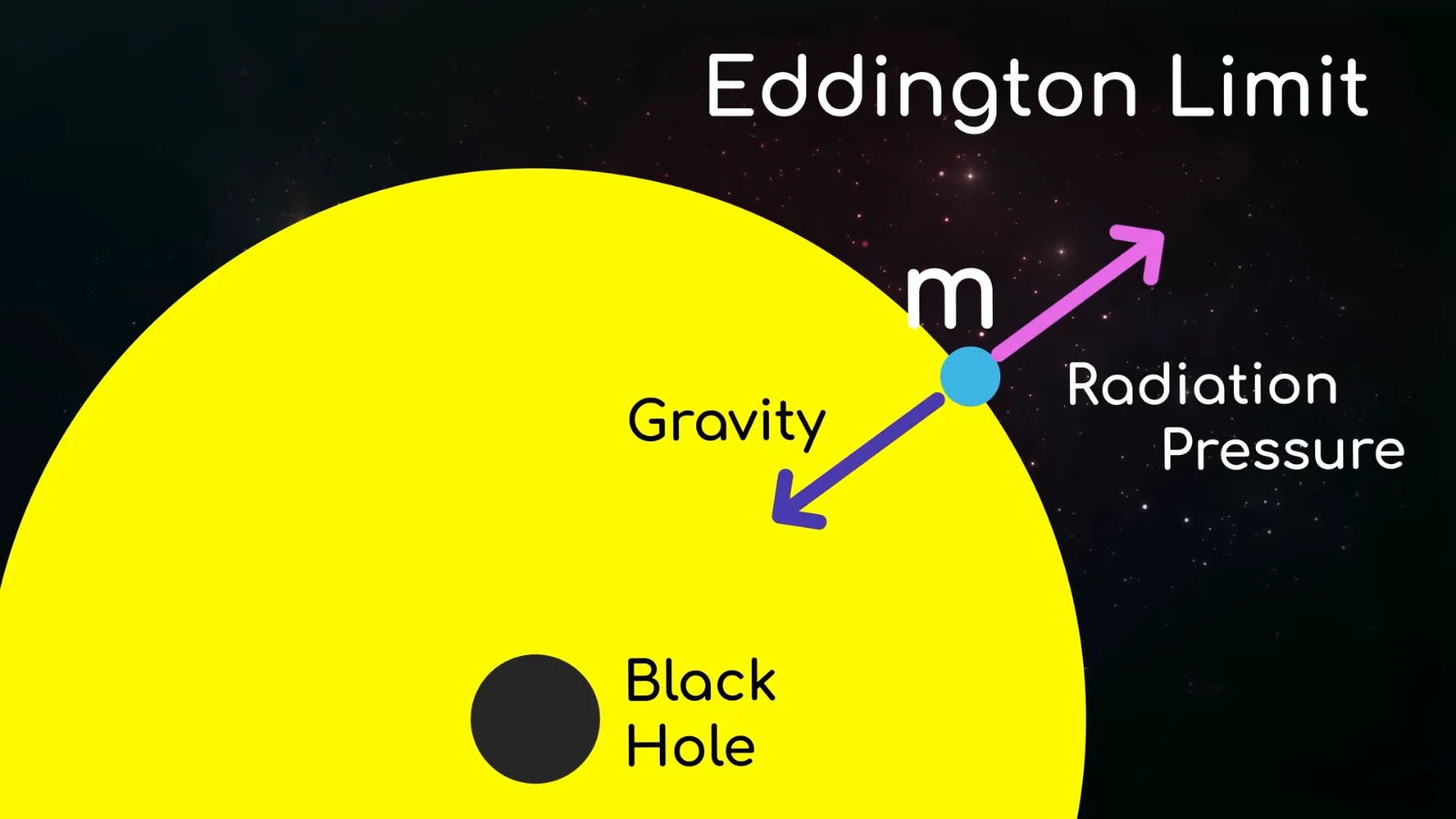

They must obey the Eddington Limit, which caps how fast matter can fall into a black hole before radiation pressure pushes the infalling material back out.

Even with ideal, nonstop feeding, stellar black holes simply shouldn’t have been able to grow into billion-solar-mass giants in such a short cosmic window.

So where did these monsters come from?

A Physics Limit That Shouldn’t Be Breakable

The Eddington Limit, proposed by Arthur Eddington in 1920, states that black holes can only consume matter up to a certain rate before incoming gas is blown away by photon pressure.

The brighter the accretion disk becomes, the harder it is for gravity to overcome this outward pressure.

For stars, this limit prevents them from growing too massive.

For black holes, it serves as a cosmic speed limit for growth.

Without violating the Eddington Limit, turning a stellar black hole into a supermassive one in just a few hundred million years is nearly impossible.

Models show it could technically happen — but the black hole would need to eat continuously, without interruption, at the maximum possible rate for its entire existence.

That scenario is about as realistic as a person eating nonstop for years without sleeping.

Worse, scientists don’t even see evidence of the “intermediate-mass” black holes that should mark this evolutionary path.

We have plenty of stellar black holes and plenty of supermassive ones — but almost none in the middle.

So cosmologists proposed another idea:

Maybe supermassive black holes weren’t grown.

Maybe they were born.

Theorists suggested that in the dense early universe, clouds of interstellar dust could collapse directly into black holes, skipping the star phase entirely.

These “direct-collapse black holes” could start life already enormous.

It was elegant.

It was possible.

But it wasn’t confirmed.

Then came LID-568 — and everything shifted again.

The Arrival of the Rule-Breaker

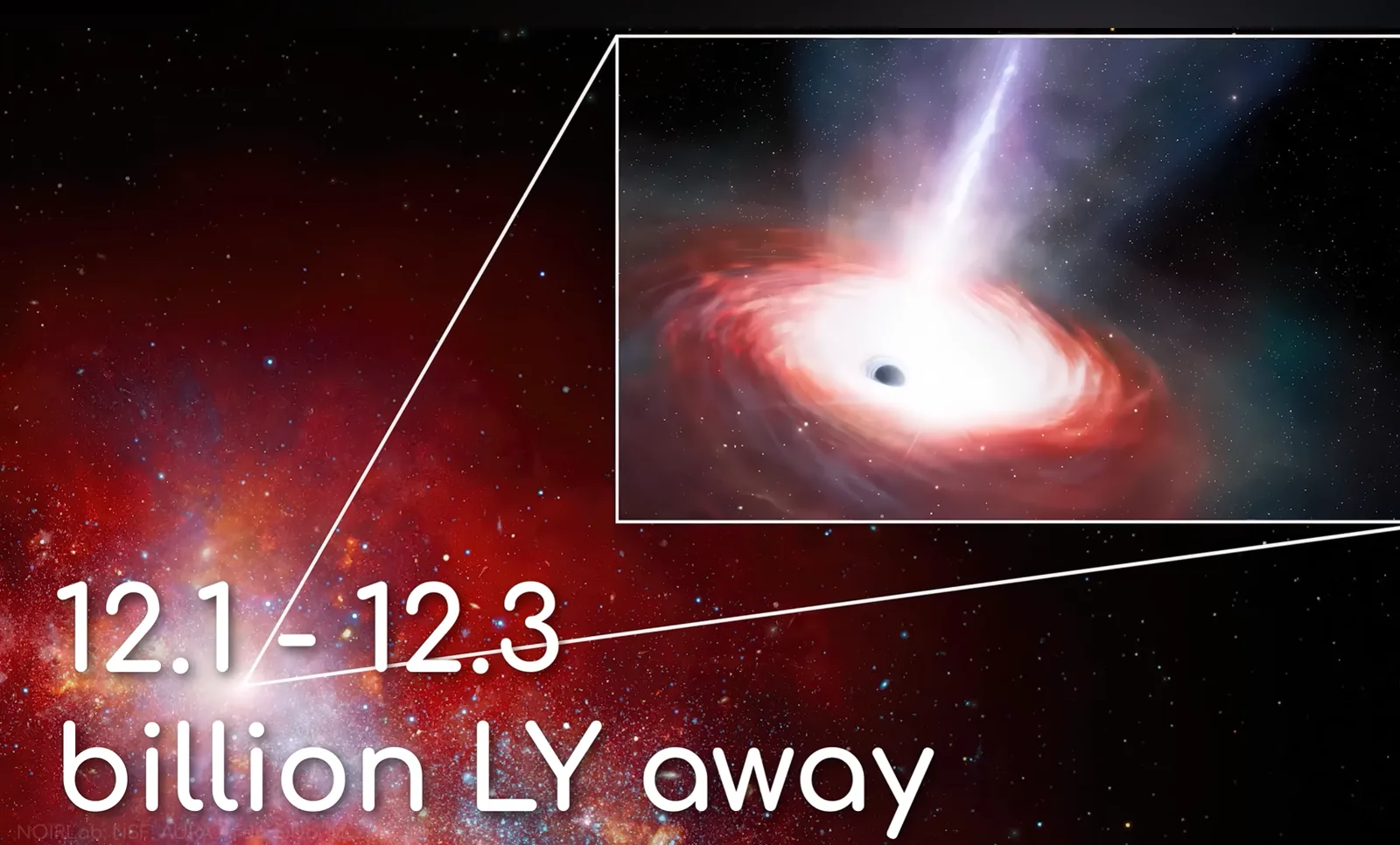

LID-568 sits between 12.

1 and 12.

3 billion light-years away, so distant that cosmic expansion has shifted its light all the way into the infrared.

Even then, it was almost too faint for detection.

It took the combined power of the Chandra-COSMOS Legacy Survey and JWST’s unprecedented resolution to detect it.

What they found stunned everyone.

The faint red glow wasn’t just a distant galaxy — it housed a black hole that was actively consuming matter at 40 times the Eddington Limit.

Not two times.

Not five times.

FORTY.

This should be impossible.

And yet, the X-ray emissions from its accretion disk made the conclusion unavoidable: LID-568 is consuming matter so quickly that it seems to be ignoring one of the most fundamental rules in astrophysics.

How Can Something Break the Eddington Limit?

As it turns out, black holes might have loopholes.

Scientists now suspect that super-Eddington accretion can occur under certain extreme conditions, such as:

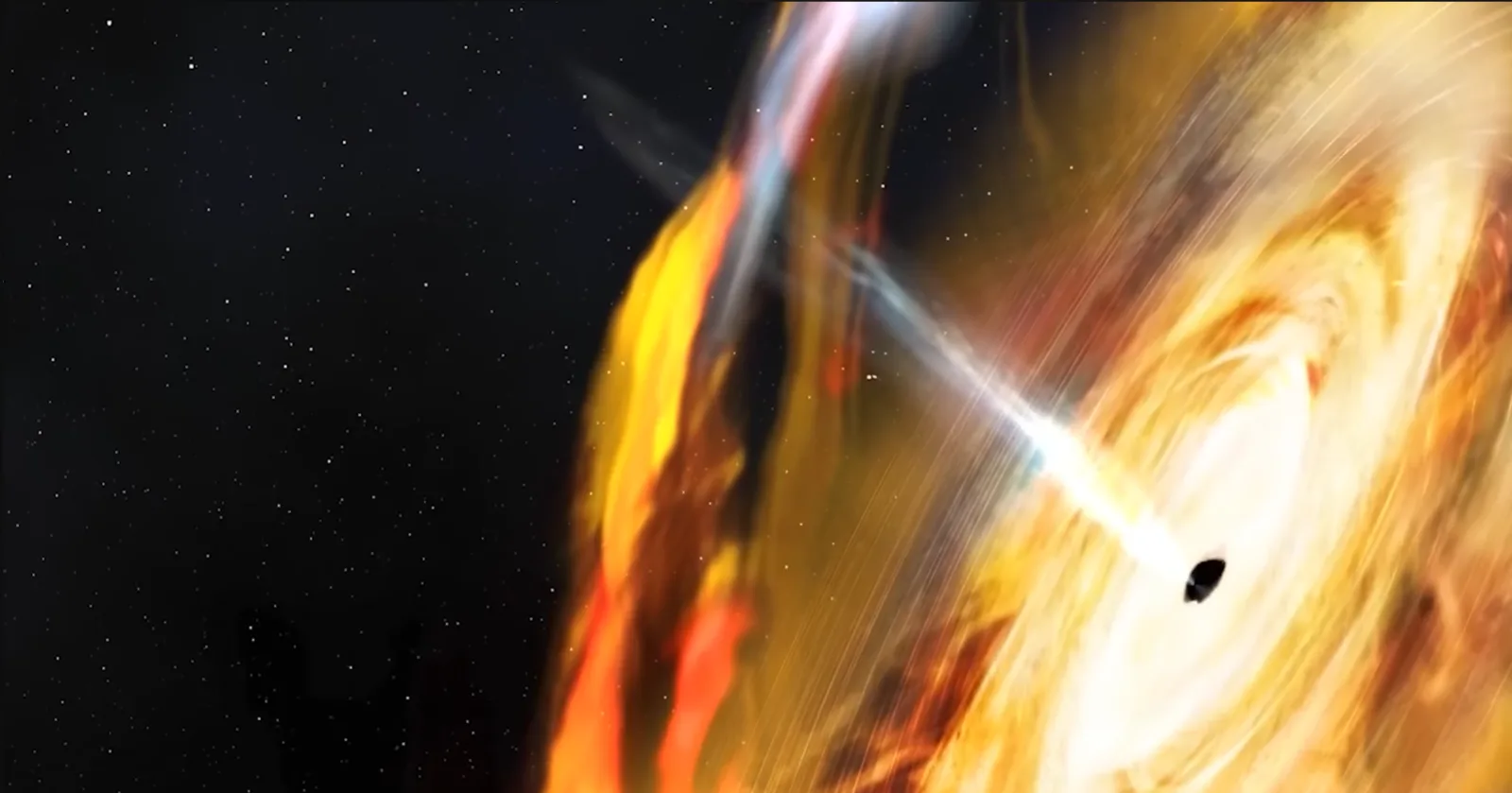

Photon Jets

If most photons are being expelled in narrow jets rather than in all directions, other regions around the black hole can feed freely.

This uneven radiation distribution might allow a black hole to gorge locally without triggering the Eddington cutoff everywhere.

“Chaotic Feeding”

Gas falling inward in irregular, clumpy bursts may briefly overwhelm radiation pressure, letting the black hole snatch food before it’s blown away.

Thick Accretion Disks

Some models show that dense, puffed-up accretion disks can trap photons briefly, lowering the outward radiation pressure and allowing faster infall.

If any of these mechanisms operate in the early universe, then early black holes could have grown far faster than we assumed — even without needing to be born massive.

And LID-568 may be the most convincing evidence yet.

Why This Matters for the Universe Itself

If super-Eddington growth is not only possible but common in the early universe, then many of the “crisis” problems triggered by JWST suddenly become explainable:- rapid early galaxy formation- unexpectedly bright early galaxies- massive black holes appearing far too soon- missing intermediate-mass black holes

LID-568 doesn’t solve the puzzle… but it shows that the missing piece exists.

But Mysteries Remain

Even with this breakthrough, huge questions linger:

Where are the intermediate black holes?

Why are early galaxies so abundant?

Do direct-collapse black holes still play a role?

How common is super-Eddington feeding?

And most importantly — what else did JWST see that we haven’t decoded yet?

The cosmos may not be broken.

But our understanding of it might be incomplete — or even outdated.

Black holes remain the gatekeepers of our deepest mysteries, and LID-568 has just torn open one of the biggest doors yet.

News

“Screaming Silence: How I Went from Invisible to Unbreakable in the Face of Family Betrayal”

“You’re absolutely right. I’ll give you all the space you need.” It’s a mother’s worst nightmare—the slow erosion of her…

“From Invisible to Unstoppable: How I Reclaimed My Life After 63 Years of Serving Everyone Else”

“I thought I needed their approval, their validation. But the truth is, I only needed myself.” What happens when a…

“When My Son Denied Me His Blood, I Revealed the Secret That Changed Everything: A Journey from Shame to Triumph”

“I thought I needed my son’s blood to save my life. It turned out I’d saved myself years ago, one…

“When My Daughter-in-Law Celebrated My Illness, I Became the Most Powerful Woman in the Room: A Journey of Betrayal, Resilience, and Reclaiming My Life”

“You taught me that dignity isn’t about what people give you, it’s about what you refuse to lose. “ What…

“When My Sister-in-Law’s Christmas Gala Turned into My Liberation: How I Exposed Their Lies and Found My Freedom”

“Merry Christmas, Victoria. ” The moment everything changed was when I decided to stop being invisible. What happens when a…

On My Son’s Wedding Day, I Took Back My Dignity: How I Turned Betrayal into a Legacy

“You were always somebody, sweetheart. You just forgot for a little while.” It was supposed to be the happiest day…

End of content

No more pages to load