Imagine a time when mammoths roamed across vast, untouched plains, and ancient humans were just beginning to explore the frontiers of a new world—long before Columbus and even before the Clovis people.

North America, back then, was a sprawling wilderness, inhabited by large megafauna and untouched by modern civilization.

Yet, recent archaeological discoveries have uncovered a reality so far beyond our expectations that it challenges everything we know about the continent’s first human inhabitants.

For decades, the history of early human migration to North America has been dominated by the Clovis people.

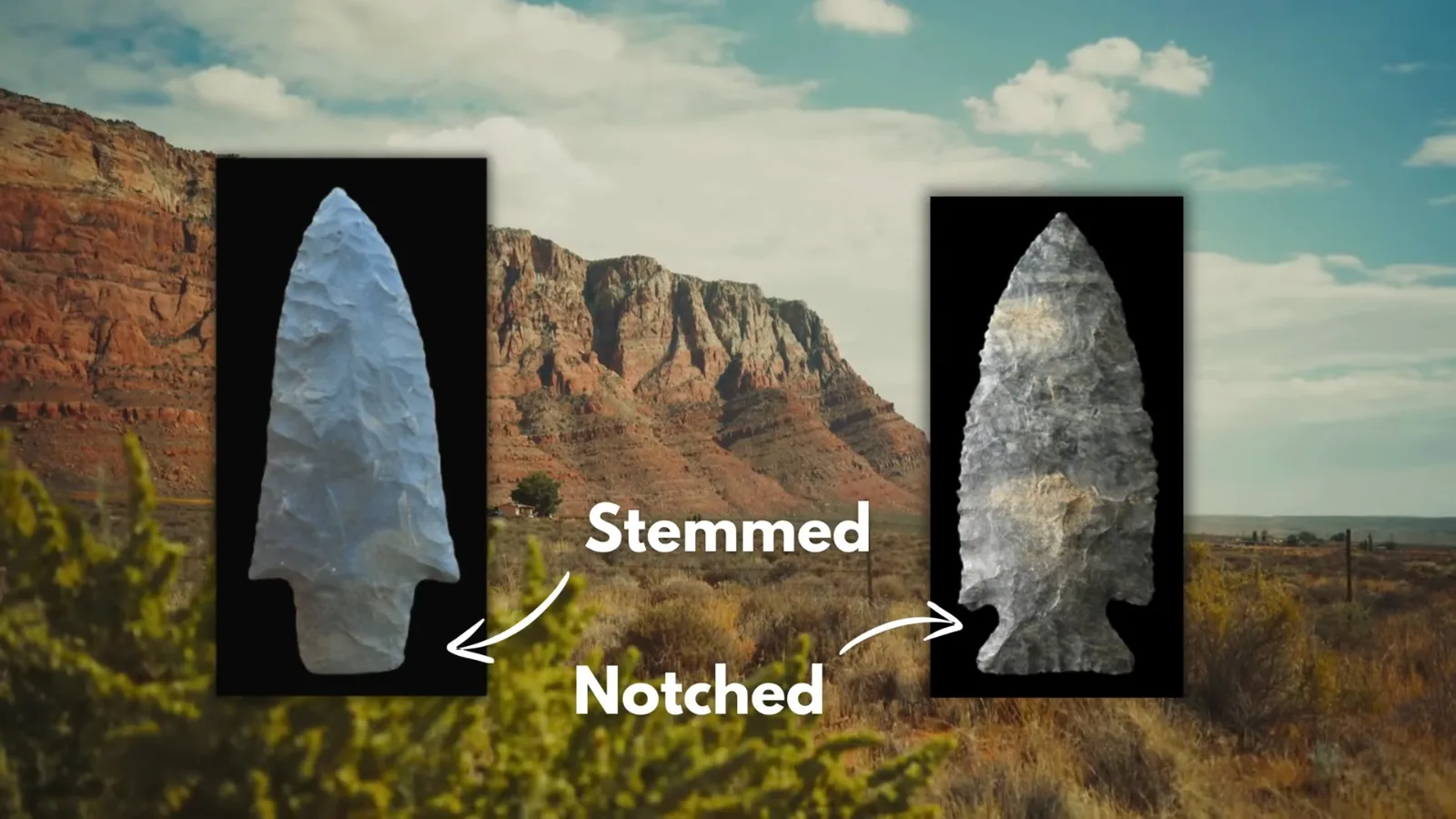

Long hailed as the first group to set foot on the continent, their distinctive stone tools were thought to mark the beginning of human civilization in the Americas.

But what if this story was wrong? What if the Clovis people weren’t the first? What if ancient human presence in North America dates back much further, and the truth has been hidden beneath layers of time? The latest archaeological sites and genetic evidence are beginning to reveal a completely different narrative—one that suggests humans were in North America long before the Clovis era.

The discovery of the Cudi Macedon site in 1992 shook the archaeological community.

Located along Route 54 in San Diego, California, this site was where workers uncovered bones of a mastodon, a giant mammal that roamed North America during the Ice Age.

What made the find even more remarkable, however, was the discovery of human tools and evidence of human activity found alongside the mastodon remains.

The age of these tools—approximately 130,000 years old—challenged everything we knew about the peopling of North America.

This discovery was one of the first pieces of evidence to suggest that humans may have arrived in the Americas far earlier than previously thought.

Archaeologists had long debated the timeline for human migration to the Americas.

The Clovis culture, with its distinctive stone tools, was widely regarded as the earliest evidence of human settlement in North America, dating back to around 13,000 years ago.

However, the Cudi Macedon site, with its evidence of human activity dating back 130,000 years, forced scientists to reconsider this timeline.

Could it be that humans were already present in the Americas before the Ice Age had even ended?

The debate surrounding the Cudi Macedon site has been ongoing, with critics suggesting that the bones could have been disturbed by construction equipment rather than humans.

However, recent studies published in 2017 support the idea that the bones were broken intentionally, likely using stone tools.

The presence of percussion marks on the bones from tools, such as hammers and anvils, indicates that humans were indeed responsible for the breakage.

These findings suggest that early humans were not only in North America earlier than previously thought, but that they were actively hunting and processing megafauna like mastodons.

As shocking as this discovery was, it wasn’t the only site to raise eyebrows.

Another important discovery was made in White Sands, New Mexico, where researchers found fossilized footprints of humans and megafauna, dated to around 22,000 years ago.

These footprints, preserved in the soft earth, were found next to the tracks of giant ground sloths and mammoths, offering further evidence that humans and these massive creatures coexisted much earlier than the Clovis culture was thought to have existed.

What makes the discovery at White Sands so important is the age of the footprints, which predates the Clovis people by thousands of years.

This new evidence forces scientists to reconsider the idea that the Clovis culture represents the first human presence in North America.

The footprints found in White Sands are some of the most significant evidence of early human activity in the Americas, suggesting that the first settlers arrived much earlier than we had imagined.

These discoveries are part of a growing body of evidence that suggests humans were living in North America during the last Ice Age.

Sites like Bluefish Caves in the Yukon, Canada, also support this theory.

Excavations at Bluefish Caves have uncovered evidence of human activity dating back around 24,000 years.

These sites are key in understanding the migration routes that early humans may have used to enter the Americas, challenging the long-held belief that humans arrived through the Bering Land Bridge after the glaciers had melted.

The evidence from Bluefish Caves suggests that humans were living in North America during the last Ice Age, and it raises important questions about the pathways early humans took to reach the continent.

The idea that humans may have arrived via coastal routes, rather than through the ice-free corridor between glaciers, is gaining support.

The discovery of early human sites in coastal regions, such as the White Sands footprints, further supports this hypothesis, offering a new perspective on how the first settlers made their way across the continent.

These findings are pushing the boundaries of what we know about early human migration and challenging the conventional narrative of the Clovis-first theory.

The fact that we are now uncovering evidence of human activity that dates back as far as 130,000 years ago means that our understanding of the history of the Americas is being rewritten.

It’s no longer just about the Clovis culture and their distinctive tools—it’s about a much earlier presence, one that predates the Ice Age and reshapes the story of human settlement in the Americas.

The new evidence coming from these archaeological sites is challenging the very foundation of what we thought we knew about early human history.

With each new discovery, scientists are uncovering more about the first people to inhabit the Americas and the paths they took to get here.

The Cudi Macedon site, White Sands, and Bluefish Caves are just the beginning.

As research continues and more ancient DNA is sequenced, we can expect to learn even more about the true origins of the people who first walked the Americas.

News

“Screaming Silence: How I Went from Invisible to Unbreakable in the Face of Family Betrayal”

“You’re absolutely right. I’ll give you all the space you need.” It’s a mother’s worst nightmare—the slow erosion of her…

“From Invisible to Unstoppable: How I Reclaimed My Life After 63 Years of Serving Everyone Else”

“I thought I needed their approval, their validation. But the truth is, I only needed myself.” What happens when a…

“When My Son Denied Me His Blood, I Revealed the Secret That Changed Everything: A Journey from Shame to Triumph”

“I thought I needed my son’s blood to save my life. It turned out I’d saved myself years ago, one…

“When My Daughter-in-Law Celebrated My Illness, I Became the Most Powerful Woman in the Room: A Journey of Betrayal, Resilience, and Reclaiming My Life”

“You taught me that dignity isn’t about what people give you, it’s about what you refuse to lose. “ What…

“When My Sister-in-Law’s Christmas Gala Turned into My Liberation: How I Exposed Their Lies and Found My Freedom”

“Merry Christmas, Victoria. ” The moment everything changed was when I decided to stop being invisible. What happens when a…

On My Son’s Wedding Day, I Took Back My Dignity: How I Turned Betrayal into a Legacy

“You were always somebody, sweetheart. You just forgot for a little while.” It was supposed to be the happiest day…

End of content

No more pages to load